Increasingly, people want to contribute to projects casually—when they want to, rather than adhering to a schedule. This is part of a broader trend of "episodic volunteering" noted by a wide range of volunteer organizations and governments. This has been attributed not only to changes in the workforce, which leave fewer people able to volunteer with less spare time to share, but also to changes in how people perceive the act of volunteering. It is no longer seen as a communal obligation, rather as a conditional activity in which the volunteer also receives benefits. Moreover, distributed revision-control systems and the network effects of GitHub, which standardize the process of making a contribution, make it easier for people to contribute casually to free/libre/open source software (FLOSS) projects.

Although it may be tempting for communities to focus on habitual contributors and newcomers who may become habitual, there are several reasons to devote attention to casual contributors. First, research has shown that casual code contributors deliver benefits to a FLOSS project. They can increase innovation and software quality, and they diffuse knowledge of the project through their social networks. Non-code contributors can also spread word of the project more widely.

Second, although many community managers might hope to convert casual contributors to habitual ones, this is not always possible. Many casual contributors are committed to the community, but can't contribute more time. Their work can be more effective if it is realistically planned. Although identifying casual contributors is often difficult until after they contribute, there can still be a strategic plan for managing them. Many of the practices recommended in this article are also applicable to newcomers and habitual contributors, therefore little additional effort is needed to incorporate casual contributors.Third, casual contributors are likely already part of your community, but not being managed effectively. Noting that casual contributors need not be one-off participants is important. Like habitual contributors, they can be retained to return repeatedly to take on new tasks. Because new participants need more time and assistance to be effective, retaining contributors is important. People who are already familiar with how the community operates are worth keeping, even if their contributions are infrequent.

Five factors for engaging and retaining casual contributors

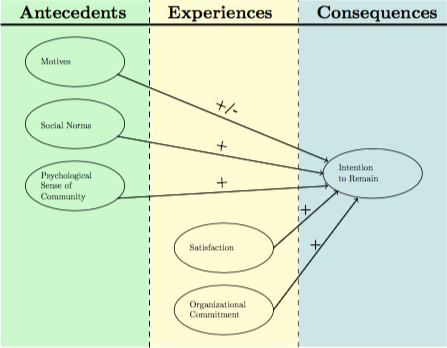

There are five factors that have been linked to engagement and retention of episodic volunteers. Figure 1 is based on the work of Hyde, Dunn, Bax, and Chambers (2016). It depicts a simplified model of the relationship between these factors and a person's intention to continue volunteering casually.

opensource.com

The factors are divided into two categories: antecedents and experiences. Antecedents are factors present before the person started to participate and tend to affect new contributors more. Experiences are the result of participation and are a more pronounced factor for longer-term casual participants. All five factors—motives, social norms, psychological sense of community, satisfaction, and organizational commitment—affect intention to remain. A volunteer's intention to remain is the single best predictor of future participation and therefore is used as a proxy for actually remaining.

- Motives: The most important motives for predicting retention among casual contributors are seeking personal benefit, enjoyment, and socializing. People who contribute to boost their CV or to fix an irritating bug are less likely to continue once their need is satisfied. By contrast, people who want entertainment or social interactions are more likely to continue if they find what they are looking for; however, they are more likely to be discouraged by the classic technical barriers to entry, such as the challenge of identifying where to change the code to fix a bug.

- Social norms: In this context, social norms refers to whether the participant perceives other people to be in favor of or opposed to the activity. As the general public is unlikely to have strong opinions about contributing to FLOSS projects, this is less of a factor for FLOSS than for other types of volunteer activities. Like any type of volunteers, however, FLOSS participants (especially non-code contributors) are quite likely to respond to a personal invitation to contribute from someone they know.

- Psychological sense of community: This refers to the feelings of support and acceptance a person derives from being in a FLOSS community. Unsurprisingly, people who feel welcomed by the community are more likely to remain. In my research, many people described inclusivity as an important component of the welcoming atmosphere that contributed to their positive feelings about the community.

- Satisfaction: This describes the match between the person's expectations and the actual experience of contributing. Satisfaction comes from feeling appreciated, having fulfilling relationships, enjoying the work, and knowing that the work is used. When people speak of their reasons for remaining, they tend to talk primarily about satisfaction.

- Organizational commitment: Feeling loyalty to and identification with the FLOSS community is most commonly found among long-term contributors. Casual contributors can be just as invested in the community as habitual contributors, which is why I prefer the term "episodic," because it doesn't imply a lack of commitment. In my investigation of FLOSS communities, I found that people who enjoy talking about their involvement are more likely to want to remain. Of course, this is not necessarily a causal relationship, but it helps identify invested participants.

Creating a strategy for managing casual contributors

Using knowledge of the five factors that contribute to the engagement and retention of casual contributors, a community can devise a strategy for managing its casual contributors. A volunteer strategy ought to involve determining the desired outcomes, identifying appropriate tasks for casual contributors, identifying and promoting practices to support the goals, and measuring the result. At the same time, the cost of incorporating casual contributors must not exceed the benefits they bring.To begin, the objective might be as simple as gaining a more comprehensive understanding of casual contributors in the community. Later, you may think of ways to motivate large numbers of people performing small amounts of work, effectively use casual contributors' contributions, or better retain casual contributors.

To find appropriate tasks, divide casual contributors into two categories: specialists and generalists. Both have limited availability, but some, which we will call "specialists," have skills that are rare among your volunteer base. Different tasks are suitable for the two types of casual contributors.

The tasks most suitable for generalists are those that:- require little effort and are quickly completed,

- have a narrow focus,

- require little upfront investment,

- can be broken into smaller parts,

- do not require skilled labor, and

- keep your habitual volunteers from larger or more critical tasks.

For specialists, there is just one recommendation:

- Separate the specialist's domain knowledge from project-specific details.

Noting that casual contributors can work on many different activities within a community is important. They are not limited to doing only one type of work; it is more a question of how to deploy them effectively. Additionally, because every community is different, community managers must consider their specific communities and how the above findings might be translated into practices.

Practices for managing casual contributors

I've identified a number of potential practices for managing casual contributors, making the link between the practice and its effect on casual contributors explicit using the five factors for engagement and retention of casual contributors.

Not all of the practices are ideal or practical for all communities, and this list is certainly not exhaustive. Many communities already have some of these practices in place, but haven't isolated their impact on casual contributors. In fact, these may be some of the most useful practices, as they can also be applied to habitual contributors.

Even if these practices are not appropriate for your community, they can provide a model of how to create a reasoned strategy for managing casual contributors.

| Practice | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Lower barriers to entry, for instance through accepting contributions directly through GitHub, a task-finding dashboard, or a container-based workspace. | People with social and entertainment motives are more likely to remain, but more likely to be discouraged by technical challenges. |

| Offer guided introductory events, such as Google Summer of Code (GSoC). | In addition to helping newcomers overcome technical challenge, events can help meet the needs of people with social motives. |

| Provide opportunities for social interaction online, such as Slack or IRC, ideally with regional variations using a local language. | People with social motives are not seeking only work-related conversations. People are often better able to express themselves in their native language. |

| Encourage existing volunteers to talk about their involvement with family and friends. Communities could provide digestible information for easy sharing. | Personal invitation, both in person and through social media, is an effective method of recruitment (social norms). People who talk about their involvement tend to be more invested (organizational commitment). |

| Use a code of conduct to state intentions. | A code of conduct—or an absence of one—sends a message about the community. Stating the community's intentions allows people to find communities that match their expectations (psychological sense of community). |

| Make sure that non-coding activities are recognized. | Potential participants may not be aware that FLOSS communities include a number of non-coding tasks, and recognizing the people who do them allows people to envision themselves in the community (psychological sense of community). It also supports satisfaction through recognition for existing contributors. |

| Collaborate with organizations with shared values but a different focus. Hive Learning Networks is one example. | Like the previous practice, this allows potential contributors to find you and feel they could belong (psychological sense of community). It can also utilize organizational commitment by getting long-term but casual contributors talking about your community to other groups they participate in. |

| Host local events and meetups (e.g., Perl Monger meetings). | Like guided introductory events, local events can help address social motives. Low-key events can also give people the opportunity to identify as potential members of the community (psychological sense of community). |

| Extend personal invitations to attend (or speak at) local events. | Personal invitations can engender feelings of inclusion (psychological sense of community) and also feelings of appreciation (satisfaction). |

| Develop awareness of your contributors' areas of expertise and request assistance (sparingly). | People tend to feel appreciated if they believe their accomplishments and skills are known (satisfaction). They are also more likely to return if they are asked. |

| Consider time-based releases, if appropriate. (In small communities this may generate excessive overhead.) | Casual contributors are often committed but busy (organizational commitment), and having a cycle helps them plan their contributions. |

| Use opt-in platforms to broadcast calls for participation. | People are often committed (organizational commitment), but need to know when their work would be most valuable to the community. |

Casual contributors are already present in FLOSS communities, but they are rarely managed deliberately. Because of the benefits they provide, especially if they can be persuaded to return, it is worth creating a strategy for engaging casual contributors. Using the five factors linked to the retention of casual contributors (motives, social norms, psychological sense of community, satisfaction and organizational commitment), and thinking about how your community can influence them, can help you arrive at a well-reasoned, tailored strategy to manage casual contributors.

How you can casually contribute to this work

These ideas are a simplified version of my ongoing PhD research. If you would like to read academic papers on this topic, you can browse my publications on my website or OrcID or follow me on ResearchGate to be informed of new publications.

Are you a community manager with opinions about this topic? I'm conducting a follow-up study and would love to have you participate. Contact me before the end of November 2017.

Learn more in Ann Barcomb's talk, Managing Casual Contributors, at Open Source Summit EU, which will be held October 23-26 in Prague.

1 Comment