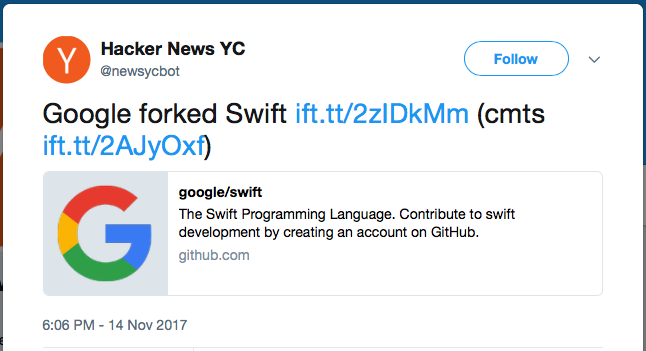

A recent headline on Hacker News caused a stir (original tweet here):

The headline, Google forked Swift, is both accurate and confusing at the same time. Why did it cause such an uproar? Because in free and open source software, the word "fork" has two meanings. Let's dig into this a little further.

The fork

The concept of forking a project has existed for decades in free and open source software. To "fork" means to take a copy of the project, rename it, and start a new project and community around the copy. Those who fork a project rarely, if ever, contribute to the parent project again. It's the software equivalent of the Robert Frost poem: Two paths diverged in a codebase and I, I took the one less traveled by…and that has made all the difference.

There can be many reasons for a project fork. Perhaps the project has lain fallow for a while and someone wants to revive it. Perhaps the company that has underwritten the project has been acquired and the community is afraid that the new parent company may close the project. Or perhaps there's a schism within the community itself, where a portion of the community has decided to go a different direction with the project. Often a project fork is accompanied by a great deal of discussion and possibly also community strife. Whatever the reason, a project fork is the copying of a project with the purpose of creating a new and separate community around it. While the fork does require some technical work, it is primarily a social action.

There have been many forks throughout the history of free and open source software. Some notable ones are MariaDB forking from MySQL, NextCloud forking from OwnCloud, and Jenkins forking from Hudson.

The clone

In Ye Olden Days, those of us who wanted to work on a codebase would fire up our CVS or our Subversion and check out the code to create a working copy in our sandbox.

Then git arrived on the scene (Mercurial, too, but it's not directly complicit in this issue). As a distributed version control system (aka a DVCS), you no longer "check out a working copy" of the primary repository. Instead, every copy of the repository can itself be primary to someone. To work in a DVCS, you must still acquire a copy of the code, but that copied code is just as valid and potentially as primary as the original. Therefore, rather than doing a checkout of the code, you must clone it. Just as in "Orphan Black" or any other good sci-fi show, the clone is identical to the original source and has the potential to become the primary repository, though that rarely happens (in FOSS, if not in sci-fi).

If you wish to contribute to a project that uses git as its version control system, you'll need to create a clone of it. For instance, to contribute to the Public_Speaking repository, you would first create a clone with this git command:

git clone https://github.com/vmbrasseur/Public_Speaking.git

This will create a local clone of the repository, against which you can make whatever changes you like. If you wish to contribute the changes back to the original repository, you must send a pull request. Unless the maintainers of the original repository grant you access to it directly, you cannot contribute to that repository without both a clone of it and a pull request against it.

Clones, unlike forks, are technical actions and do not need to involve the community or any social changes.

The complication

Nothing is ever really simple with free and open source software, so naturally there's a complication to this entire process.

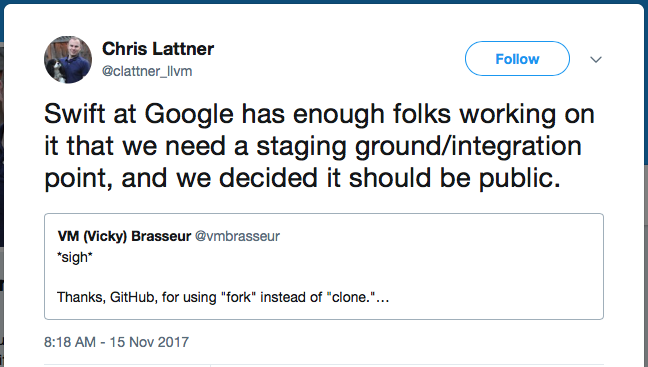

When GitHub launched back in 2008, it chose the word fork to represent the action of a git clone command. When you fork a project on GitHub, you are actually just creating a clone of it—a copy on which you can perform your work. It is entirely possible that from here you may choose to fork the project in the original sense: create a separate project and associated community rather than simply sending pull requests back to the original project. However, nearly all people who fork a GitHub project only intend to create a personal working copy, a clone. This overloading of the word fork has caused more than a little bit of confusion in free and open source software communities, most recently creating the scare that Google might have forked (in the original sense) the Swift programming language (implying that it was creating a new and separate project), rather than what it actually did: clone the project in order to contribute back to it, as any good free and open source citizen would.

(original Chris Lattner tweet here)

So you see, usually your fork is a clone, but sometimes it's a fork. It all depends on whether you're simply contributing back to the original community (clone) or trying to form a new one (fork)…or if you're using GitHub, in which case your fork is a clone and vice versa.

6 Comments