While the options for Linux computers from commercial vendors are still needles in the proverbial haystack of OEM Windows equipment out there, there are more and more options available to a consumer who wants a good, solid device that's ready-to-use with no messing around.

Still, there are more Linux OEM computers than I could look at for one article—and the options tend to be different in Europe than they are in the United States, with providers like Entroware that don't ship to the latter at all.

In this article, I look at offerings from three of the most well-known Linux OEMs on the western side of the pond: ZaReason, System76, and Dell.

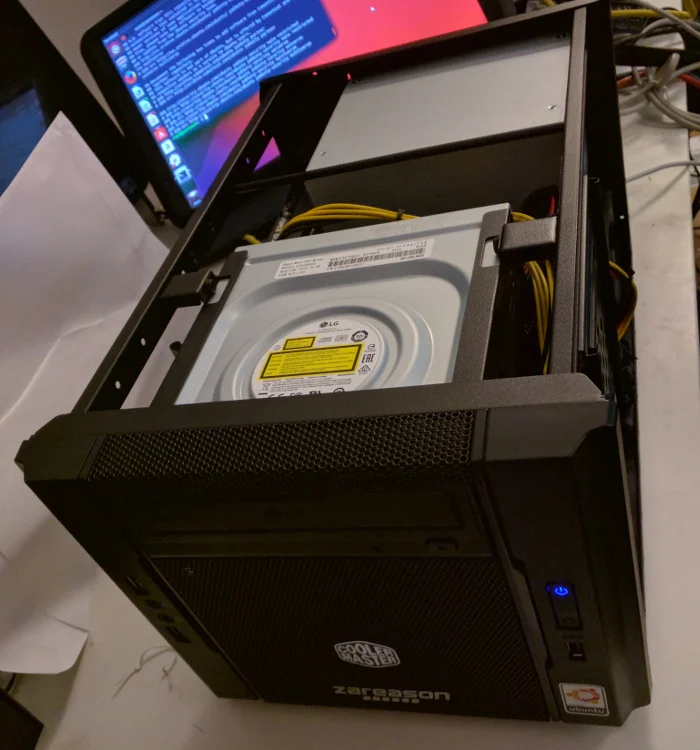

ZaReason Mediabox 6550

When I sent out a letter to several manufacturers, I asked specifically for Linux laptops, because that's what I'd planned on writing about. But whenever they'd ask which part out of the catalog I wanted, my response was always, "send me what you want Opensource.com readers to see." ZaReason CEO Cathy Malmrose took me at my word and didn't send me a laptop at all!

The ZaReason Mediabox 6550 is a desktop-style PC in a low, cube-like, home theater PC (HTPC) case. Specifically, it's a CoolerMaster 130 Elite. The default build, at $500 with a Pentium G, onboard video, and a 500GB conventional hard drive, would make a good HTPC. The one I received was considerably more tricked out, with a 3.9GHz i3-7100, a GeForce GTX 1060, and a 100GB NVMe SSD—a pretty solid midrange gaming box, for a reasonable US $1,055.

The MediaBox has plenty of USB3 ports, a gigabit Ethernet interface, and even an 802.11ac Intel 8260 2x2 WiFi card, complete with antennas.

That's a 15" portable monitor on top of the MediaBox. The GTX 1060 and that elderly 22" Acer LED monitor you see sitting on top of the server next to it didn't really get along, unfortunately.

A fairly uninteresting peek down into the MediaBox's opened shell. This case makes for a pretty compact build, so there's really not much to see without disassembling the whole thing.

The machine is quiet, fast, and does what it's supposed to. It boots in just a few seconds and automatically logs you into an Ubuntu Yakkety (16.10) desktop as a default user: user zareason, password zareason.

This was the one real gripe I had about the machine. On the one hand, it's appealing not to have to click through the usual OEM install experience... but on the other, default logins of brandname:brandname are a really bad security gaffe since too many people won't change them. (It is, of course, trivial enough to create your own user account and delete the default one entirely.) This also means that you won't get optimized mirrors for your location when you unbox it; a vanilla install of Ubuntu from my house puts us.archive.ubuntu.com in the sources list, but this machine used archive.ubuntu.com instead.

Following along the path of "convenient for the end user," all proprietary drivers for the hardware—both the NVidia proprietary binary and Intel's microcode driver for the CPU—were already installed and in use. On the one hand, that's not likely to make RMS happy. On the other hand, let's be honest—who buys a GTX 1060 and then runs nouveau drivers?

The biggest strength of ZaReason's Mediabox is, paradoxically, the easiest thing to pick at: It's a box that a hobbyist could build out of stock parts. That really is a strength, though—it's pretty much an ideal build, consisting of the right parts competently assembled, that you didn't have to choose and buy individually and put together yourself... and that won't be impossible to work on due to proprietary parts nobody but the OEM ever made. If you need an HTPC or gaming machine, it's hard to go wrong here.

Price as reviewed: US $1,055

- Ubuntu Yakkety Yak (16.10 intermediate release)

- Intel i3-7100 CPU at 3.9 GHz

- 16GB DDR4 SDRAM

- GeForce GTX 1060 video

- 100GB NVMe SSD

- DVD-RW

- Realtek RTL8168 gigabit Ethernet

- Intel 8260 802.11ac WiFi

System76 Oryx Pro

System76's Oryx Pro laptop is not an airy, lightweight consumer device. It's an intimidating, portable battle station with an undeniable gravitas to go along with its all-aluminum-alloy, 6 lb. heft; it wants you to know it is a serious machine being used by a serious developer/admin/gamer/executive, and it gets that message across loud and clear.

This is, without a doubt, one of the <em>nicest</em> looking laptops I've ever had the pleasure of playing with.

There's no way to get across how bright and bold the keyboard backlighting on the Oryx Pro really is without a picture. Unfortunately, while there's probably a way of getting a decent-looking shot of an open laptop with a bright screen and keyboard backlight, <em>I</em> don't know how to!

The left side of the Oryx Pro has a fan exhaust, an HDMI output, a USB3 port, and two mini-DisplayPort video outputs.

Oryx Pro's right side features headphone/line/mic audio jacks, a Compact Flash reader, a MultiMedia Card (MMC) reader, two USB3-C (the new symmetrical USB interface) ports, another standard USB3, a Realtek 8168 gigabit Ethernet jack, and a Kensington security lock port.

The benefits of Oryx Pro's no-compromises hefty build don't stop at its menacing good looks: This is without a doubt the most solid feeling laptop I've ever used.

The screen hinges are very firm and tight and feel like they'll stay that way for a long time. There's zero flex in the chassis or under the keyboard as you pick the machine up, move it around, or type on it, no matter how enthusiastic you get. Finally, while 6 lbs is undeniably heavy, the Oryx Pro isn't as bulky as you might think—it's a full size 15.6" laptop, and no doubt about it, but it isn't one bit thicker than it needs to be to fit its full-size Ethernet jack on the side.

The USB3 ports are spaced all the way around the laptop, so it's pretty easy to accommodate wherever you set up and whichever thing has the short cord (or the really long back sticking out). The touchpad and keyboard both feel really nice, and I certainly appreciate the full layout with a number pad on the right. The backlighting will accommodate pretty much anything you want it to do; you can change its color through white/red/blue/green/cyan, and turn its brightness up or down through four or five levels, by using the Fn key with clearly-marked controls on the number-pad.

Finally, the Oryx Pro features an M.2 PCIe system drive with bays for not just one but two additional, optional 2.5" SATA drives if you need them. This is a pretty amazing feature if you need to do demos or move client data around in large quantities, and I'm not sure where except System76 you'd find it.

Unlike the ZaReason Mediabox, the Oryx Pro boots into Canonical's standard "first login" setup for desktop Ubuntu—the OS is already installed, but no user accounts are set until you create your own and give it a password. This does mean you need to spend an extra 15 or 20 seconds before you can start playing... but it also means there's no default system account lurking and waiting for someone to potentially exploit it. Proprietary drivers for its CPU and GPU are pre-installed and operational.

The Oryx Pro starts at US $1,399, and configuration as reviewed was US $1,763. If you want the thinnest, lightest thing you can find or the longest battery life (my Oryx Pro was good for about three hours of moderate use, fully charged), this isn't the machine for you. But if what you really want is a hard-core desktop machine that you can put in your lap wherever you go, it doesn't get any better than this.

Price as reviewed: US $1,763

- Ubuntu Yakkety Yak (16.10 intermediate release)

- Intel i7-7700HQ CPU

- 32GB DDR4 SDRAM

- GeForce GTX 1060 video

- 250GB NVMe SSD

- 15.6" 1080p display

- Full layout backlit keyboard with number pad

- Realtek RTL8168 gigabit Ethernet

- Intel 8260 802.11ac WiFi

Dell XPS 13 Developer Edition

Dell's XPS 13 Developer Edition gets a lot of press, but it's not Dell's first time to the rodeo—Dell was one of the first big manufacturers to dip its toes into the OEM Linux space all the way back in 2009, with the Mini 10 and Mini 10v line of Atom-powered netbooks (of which I owned several). Back then, the Linux options honestly weren't that great—I bought them eagerly to "vote with my wallet," but Job One was paving them clean and reinstalling stock Ubuntu (or, back then, Ubuntu Netbook Remix) to get rid of that "you bought a corporate thing with corporate crud on it" feel.

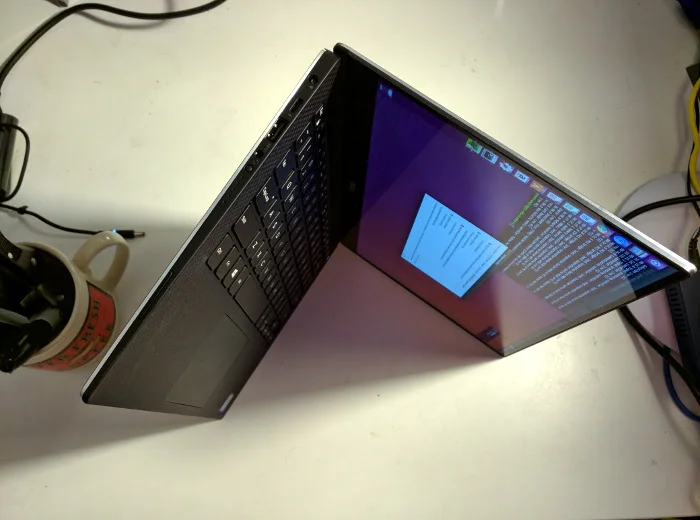

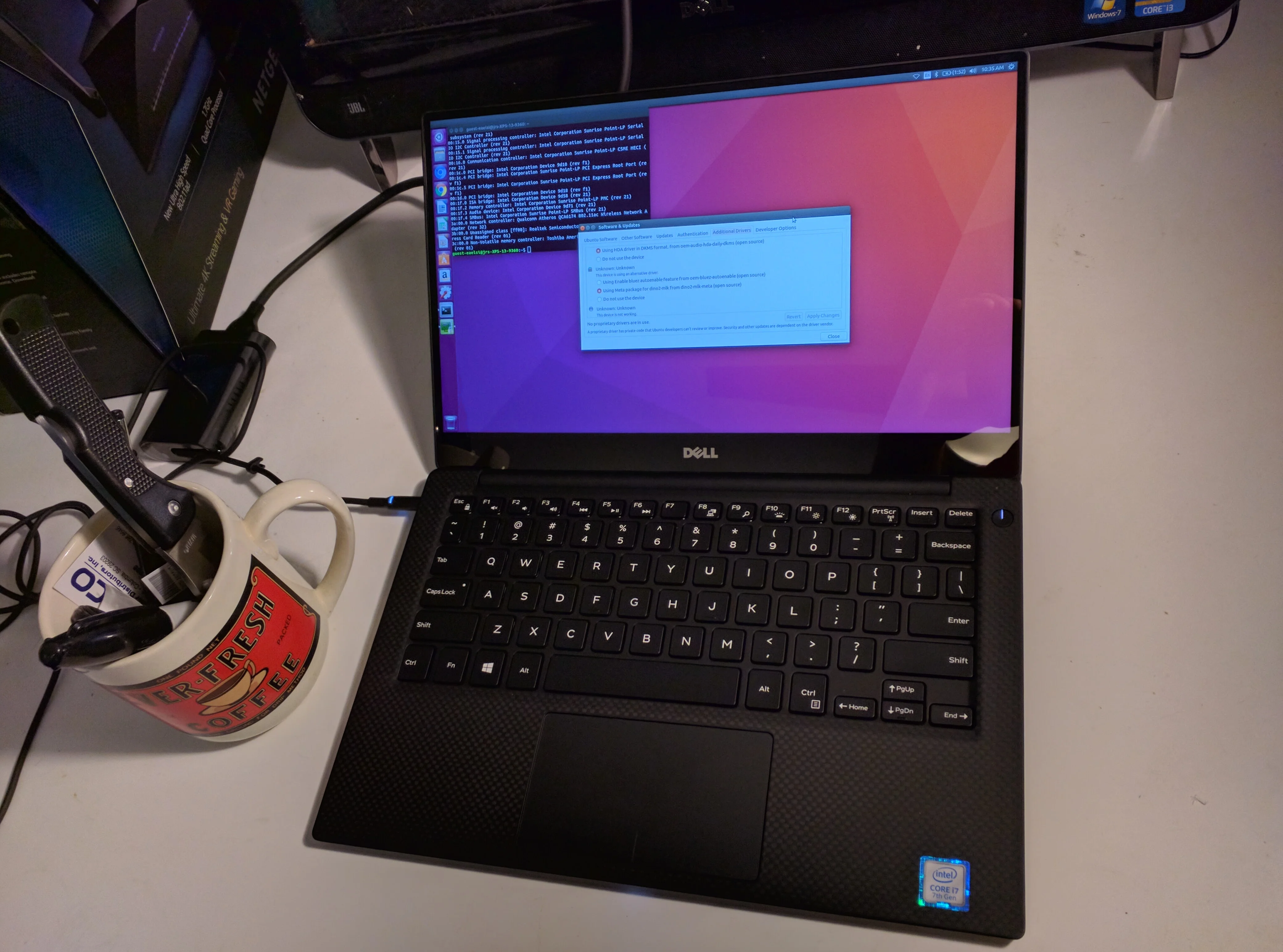

I am pleased to say that Dell has come a long way since then. As great as the XPS 13 looks physically, it's matched on the inside by pretty amazing attention to free and open source detail from one of the world's largest corporate manufacturers. Mine had Ubuntu 16.04 LTS installed—a nice departure from the usual intermediate builds!—and while the full, proprietary Google Chrome browser was installed and available, the open source Chromium build was not only installed, but in pole position on the launcher. Similarly, Dell was careful not to install any proprietary hardware drivers on the XPS 13—while there are several alternate drivers provided by Dell in use, they're all marked "open source" in the Additional Drivers dialog, and Intel's proprietary microcode driver is available but not installed or running.

Back to those physical features, though—the XPS 13 is pretty much the perfect size for anyone wanting a super-small, thin, light laptop they can still actually work with. Dell's nearly bezel-less display allows it to pack that 13" display into an actual device smaller than an 11.6" Chromebook—no small feat. At 2 lb. 14 oz., it's less than half the weight of the Oryx Pro, and the battery life is just plain crazy—somewhere well north of nine hours. I used mine over the course of an entire three-day weekend for an hour or two here or there—letting the laptop sleep, not power off, in between sessions—without ever needing to recharge. The single, device-wide hinge makes it feel much sturdier than most laptops its size, and the keyboard was also quite good.

In many ways, the Oryx Pro and the XPS 13 are two sides of the same coin. The Oryx Pro aims for people who want a serious desktop computer they can take with them; the XPS 13 aims for people who want a seriously small, convenient laptop they can still do real work on. They both have an aluminum alloy chassis and extremely sturdy internals for a high-quality, no-flex feel. Although the XPS 13 is objectively light at less than 3 lb., it's surprisingly heavier than it looks due to that same solid construction. Finally, the Dell's i7-7500U isn't really a match for the i7-7700HQ in the Oryx Pro, but it's hard to argue with the extra five-plus hours of battery life you get in return!

Visually, the XPS13 doesn't have the sheer gravitas of the Oryx Pro. The understated elegance of a simple slab of brushed aluminum goes a long way, though.

On the left, we see a headphone jack (take that, Apple!), a USB3 port, a USB Type-C Thunderbolt port, and the power jack.

XPS 13's right side features an SD card reader, USB3 jack (though I wish they'd use the blue internals, instead of that near-microscopic "SS" screen print, to mark it!), and Kensington security slot.

There's nothing at all on the back of the XPS 13 but that big screen hinge, making it perfect for working in cramped spaces—like the seat of an airplane.

My XPS 13 came with a QCA6174 802.11ac 2x2 WiFi adapter—and if you're wondering why Qualcomm and not Intel, the answer is that this is a Multi-user MIMO (MU-MIMO) adapter. That doesn't mean too much right now, but it will become increasingly important over the next few years as higher-end smartphones, tablets, and routers all support the feature. In a nutshell, MU-MIMO won't do you any good unless your router and several of your devices support it; but networks that have at least several MU-MIMO-capable devices will operate much more reliably than those that don't.

This particular XPS 13 also came with a 4K touchscreen display. This was unfortunate because Ubuntu—like Windows—just isn't ready for near-microscopic pixels. The desktop environment scales natively and easily to full resolution, and quite a few applications do too—but "quite a few" and "all" are two very different things. For applications that don't support HiDPI (high dots per inch) scaling (like Pinta, which I installed while using the laptop over a long weekend), the interface buttons are so small, it's hard to tap or click them at all, let alone read anything on them.

It didn't take long to decide I'd had enough of 4K and just set the display to 1080p. This produced a beautiful and usable display... but it also exposed a corner-case bug in Intel's graphics driver. With the 4K display in 4K it was fine, and with a 1080p display at 1080p you'd be fine... but downscale the 4K display to 1080p, and you get occasional rapid "glitching" in full-screen browser windows. For most people, it's annoying but no big deal; for photosensitive epileptics, it might be enough to trigger a seizure.

The silver lining to encountering this bug was seeing, once again, how far Dell has come as a Linux OEM. When I reported the bug, I honestly didn't expect much. But Dell's Linux support department immediately asked for video of the glitch happening and used it to file a private bug with Canonical upstream. From there, Dell and Canonical tracked it down to bugs filed already on Launchpad and upstream with Xorg at freedesktop.org. (The bug has since been addressed and is fixed in 16.10 and later, or in the hardware enablement [HWE] kernels for 16.04.) This was not only objectively good support, but some of the most Linux-friendly support I've ever received from any company.

You can get into an i5-powered, non-touchscreen 1080p XPS 13 with 4GB of RAM starting at $850; the version I reviewed here came in at just under $2,000.

Price as reviewed: $1,975

- Ubuntu Xenial Xerus (16.04 LTS release)

- Intel i7-7500U CPU

- 16GB DDR4 SDRAM

- Intel onboard video

- Toshiba 512GB NVMe SSD

- 13" 4K HiDPI display

- USB-C wired Ethernet adapter

- Qualcomm QCA6174 802.11ac MU-MIMO (!) WiFi

21 Comments