Secure communication is quickly becoming the norm for today's web. In July 2018, Google Chrome plans to start showing "not secure" notifications for all sites transmitted over HTTP (instead of HTTPS). Mozilla has a similar plan. While cryptography is becoming more commonplace, it has not become easier to understand. Let's Encrypt designed and built a wonderful solution to provide and periodically renew free security certificates, but if you don't understand the underlying concepts and pitfalls, you're just another member of a large group of cargo cult programmers.

Attributes of secure communication

The intuitively obvious purpose of cryptography is confidentiality: a message can be transmitted without prying eyes learning its contents. For confidentiality, we encrypt a message: given a message, we pair it with a key and produce a meaningless jumble that can only be made useful again by reversing the process using the same key (thereby decrypting it). Suppose we have two friends, Alice and Bob, and their nosy neighbor, Eve. Alice can encrypt a message like "Eve is annoying", send it to Bob, and never have to worry about Eve snooping on her.

For truly secure communication, we need more than confidentiality. Suppose Eve gathered enough of Alice and Bob's messages to figure out that the word "Eve" is encrypted as "Xyzzy". Furthermore, Eve knows Alice and Bob are planning a party and Alice will be sending Bob the guest list. If Eve intercepts the message and adds "Xyzzy" to the end of the list, she's managed to crash the party. Therefore, Alice and Bob need their communication to provide integrity: a message should be immune to tampering.

We have another problem though. Suppose Eve watches Bob open an envelope marked "From Alice" with a message inside from Alice reading "Buy another gallon of ice cream." Eve sees Bob go out and come back with ice cream, so she has a general idea of the message's contents even if the exact wording is unknown to her. Bob throws the message away, Eve recovers it, and then every day for the next week drops an envelope marked "From Alice" with a copy of the message in Bob's mailbox. Now the party has too much ice cream and Eve goes home with free ice cream when Bob gives it away at the end of the night. The extra messages are confidential, and their integrity is intact, but Bob has been misled as to the true identity of the sender. Authentication is the property of knowing that the person you are communicating with is in fact who they claim to be.

Information security has other attributes, but confidentiality, integrity, and authentication are the three traits you must know.

Encryption and ciphers

What are the components of encryption? We need a message which we'll call the plaintext. We may need to do some initial formatting to the message to make it suitable for the encryption process (padding it to a certain length if we're using a block cipher, for example). Then we take a secret sequence of bits called the key. A cipher then takes the key and transforms the plaintext into ciphertext. The ciphertext should look like random noise and only by using the same cipher and the same key (or as we will see later in the case of asymmetric ciphers, a mathematically related key) can the plaintext be restored.

The cipher transforms the plaintext's bits using the key's bits. Since we want to be able to decrypt the ciphertext, our cipher needs to be reversible too. We can use XOR as a simple example. It is reversible and is its own inverse (P ^ K = C; C ^ K = P) so it can both encrypt plaintext and decrypt ciphertext. A trivial use of an XOR can be used for encryption in a one-time pad, but it is generally not practical. However, it is possible to combine XOR with a function that generates an arbitrary stream of random data from a single key. Modern ciphers like AES and Chacha20 do exactly that.

We call any cipher that uses the same key to both encrypt and decrypt a symmetric cipher. Symmetric ciphers are divided into stream ciphers and block ciphers. A stream cipher runs through the message one bit or byte at a time. Our XOR cipher is a stream cipher, for example. Stream ciphers are useful if the length of the plaintext is unknown (such as data coming in from a pipe or socket). RC4 is the best-known stream cipher but it is vulnerable to several different attacks, and the newest version (1.3) of the TLS protocol (the "S" in "HTTPS") does not even support it. Efforts are underway to create new stream ciphers with some candidates like ChaCha20 already supported in TLS.

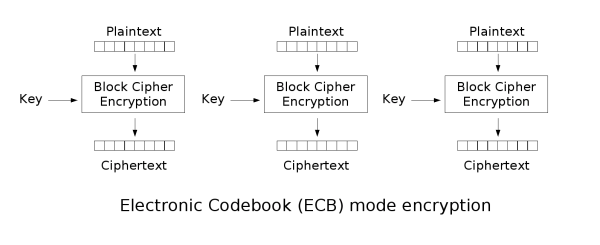

A block cipher takes a fix-sized block and encrypts it with a fixed-sized key. The current king of the hill in the block cipher world is the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), and it has a block size of 128 bits. That's not very much data, so block ciphers have a mode that describes how to apply the cipher's block operation across a message of arbitrary size. The simplest mode is Electronic Code Book (ECB) which takes the message, splits it into blocks (padding the message's final block if necessary), and then encrypts each block with the key independently.

You may spot a problem here: if the same block appears multiple times in the message (a phrase like "GET / HTTP/1.1" in web traffic, for example) and we encrypt it using the same key, we'll get the same result. The appearance of a pattern in our encrypted communication makes it vulnerable to attack.

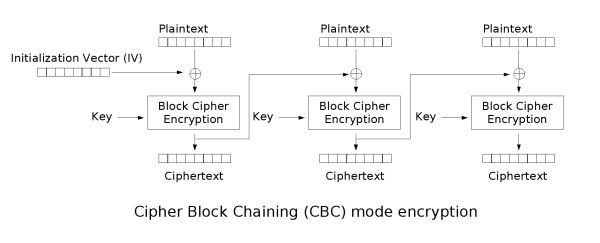

Thus there are more advanced modes such as Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) where the result of each block's encryption is XORed with the next block's plaintext. The very first block's plaintext is XORed with an initialization vector of random numbers. There are many other modes each with different advantages and disadvantages in security and speed. There are even modes, such as Counter (CTR), that can turn a block cipher into a stream cipher.

In contrast to symmetric ciphers, there are asymmetric ciphers (also called public-key cryptography). These ciphers use two keys: a public key and a private key. The keys are mathematically related but still distinct. Anything encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted with the private key and data encrypted with the private key can be decrypted with the public key. The public key is widely distributed while the private key is kept secret. If you want to communicate with a given person, you use their public key to encrypt your message and only their private key can decrypt it. RSA is the current heavyweight champion of asymmetric ciphers.

A major downside to asymmetric ciphers is that they are computationally expensive. Can we get authentication with symmetric ciphers to speed things up? If you only share a key with one other person, yes. But that breaks down quickly. Suppose a group of people want to communicate with one another using a symmetric cipher. The group members could establish keys for each unique pairing of members and encrypt messages based on the recipient, but a group of 20 people works out to 190 pairs of members total and 19 keys for each individual to manage and secure. By using an asymmetric cipher, each person only needs to guard their own private key and have access to a listing of public keys.

Asymmetric ciphers are also limited in the amount of data they can encrypt. Like block ciphers, you have to split a longer message into pieces. In practice then, asymmetric ciphers are often used to establish a confidential, authenticated channel which is then used to exchange a shared key for a symmetric cipher. The symmetric cipher is used for subsequent communications since it is much faster. TLS can operate in exactly this fashion.

At the foundation

At the heart of secure communication are random numbers. Random numbers are used to generate keys and to provide unpredictability for otherwise deterministic processes. If the keys we use are predictable, then we're susceptible to attack right from the very start. Random numbers are difficult to generate on a computer which is meant to behave in a consistent manner. Computers can gather random data from things like mouse movement or keyboard timings. But gathering that randomness (called entropy) takes significant time and involve additional processing to ensure uniform distributions. It can even involve the use of dedicated hardware (such as a wall of lava lamps). Generally, once we have a truly random value, we use that as a seed to put into a cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generator Beginning with the same seed will always lead to the same stream of numbers, but what's important is that the stream of numbers descended from the seed don't exhibit any pattern. In the Linux kernel, /dev/random and /dev/urandom, operate in this fashion: they gather entropy from multiple sources, process it to remove biases, create a seed, and can then provide the random numbers used to generate an RSA key for example.

Other cryptographic building blocks

We've covered confidentiality, but I haven't mentioned integrity or authentication yet. For that, we'll need some new tools in our toolbox.

The first is the cryptographic hash function. A cryptographic hash function is meant to take an input of arbitrary size and produce a fixed size output (often called a digest). If we can find any two messages that create the same digest, that's a collision and makes the hash function unsuitable for cryptography. Note the emphasis on "find"; if we have an infinite world of messages and a fixed sized output, there are bound to be collisions, but if we can find any two messages that collide without a monumental investment of computational resources, that's a deal-breaker. Worse still would be if we could take a specific message and could then find another message that results in a collision.

As well, the hash function should be one-way: given a digest, it should be computationally infeasible to determine what the message is. Respectively, these requirements are called collision resistance, second preimage resistance, and preimage resistance. If we meet these requirements, our digest acts as a kind of fingerprint for a message. No two people (in theory) have the same fingerprints, and you can't take a fingerprint and turn it back into a person.

If we send a message and a digest, the recipient can use the same hash function to generate an independent digest. If the two digests match, they know the message hasn't been altered. SHA-256 is the most popular cryptographic hash function currently since SHA-1 is starting to show its age.

Hashes sound great, but what good is sending a digest with a message if someone can tamper with your message and then tamper with the digest too? We need to mix hashing in with the ciphers we have. For symmetric ciphers, we have message authentication codes (MACs). MACs come in different forms, but an HMAC is based on hashing. An HMAC takes the key K and the message M and blends them together using a hashing function H with the formula H(K + H(K + M)) where "+" is concatenation. Why this formula specifically? That's beyond this article, but it has to do with protecting the integrity of the HMAC itself. The MAC is sent along with an encrypted message. Eve could blindly manipulate the message, but as soon as Bob independently calculates the MAC and compares it to the MAC he received, he'll realize the message has been tampered with.

For asymmetric ciphers, we have digital signatures. In RSA, encryption with a public key makes something only the private key can decrypt, but the inverse is true as well and can create a type of signature. If only I have the private key and encrypt a document, then only my public key will decrypt the document, and others can implicitly trust that I wrote it: authentication. In fact, we don't even need to encrypt the entire document. If we create a digest of the document, we can then encrypt just the fingerprint. Signing the digest instead of the whole document is faster and solves some problems around the size of a message that can be encrypted using asymmetric encryption. Recipients decrypt the digest, independently calculate the digest for the message, and then compare the two to ensure integrity. The method for digital signatures varies for other asymmetric ciphers, but the concept of using the public key to verify a signature remains.

Putting it all together

Now that we have all the major pieces, we can implement a system that has all three of the attributes we're looking for. Alice picks a secret symmetric key and encrypts it with Bob's public key. Then she hashes the resulting ciphertext and uses her private key to sign the digest. Bob receives the ciphertext and the signature, computes the ciphertext's digest and compares it to the digest in the signature he verified using Alice's public key. If the two digests are identical, he knows the symmetric key has integrity and is authenticated. He decrypts the ciphertext with his private key and uses the symmetric key Alice sent him to communicate with her confidentially using HMACs with each message to ensure integrity. There's no protection here against a message being replayed (as seen in the ice cream disaster Eve caused). To handle that issue, we would need some sort of "handshake" that could be used to establish a random, short-lived session identifier.

The cryptographic world is vast and complex, but I hope this article gives you a basic mental model of the core goals and components it uses. With a solid foundation in the concepts, you'll be able to continue learning more.

Thank you to Hubert Kario, Florian Weimer, and Mike Bursell for their help with this article.

1 Comment