If you search the internet for "unexpected API behavior," you'll soon discover that no one likes when an API doesn't work as anticipated. When you consider the increasing number of APIs, continuous development, and delivery of the services built on top of them, it's no surprise that APIs can diverge from their expected behavior. This is why API test coverage is critical for success. For years, we have created unit and functional tests for our APIs, but where do we go from there?

Single source of truth

To understand contract testing, you must first understand how the idea of a single source of truth (SSOT) fits into API development. Wikipedia describes it as the "practice of structuring information models and associated data schema such that every data element is stored exactly once." This is a wordy way of saying an SSOT is something everyone agrees on and you don't have to repeat yourself. It might be an agreement between backend and frontend engineering teams, between maintainers, or maybe between a software architect and their team.

Because development happens in a lot of different teams, time zones, and mediums, having something to look to for the SSOT is helpful. Within API development, this is where the OpenAPI Specification becomes handy.

What is the OpenAPI Specification?

The OpenAPI Specification (formerly known as Swagger) is a vendor-neutral, portable, and open API description format that standardizes how REST APIs are described. There are other formats available (e.g., API Blueprint and RAML) but, with the creation of the OpenAPI Initiative, all evidence points to OpenAPI as the most popular API specification format right now.

I see the OpenAPI Specification (OAS) as a bridge that helps us communicate about APIs. Since APIs are a mixture of humans and machines, OAS is a bridge between these machines and other humans, a common language. As with any standard, it uses a centralized language to describe things. OpenAPI's descriptions of specific properties were made so machines can process them (e.g., testing).

Having an OAS for your API also allows you to:

- Generate API reference documentation

- Have a development contract

- Set up mock servers and prototype your APIs

- Create server stubs or libraries based on the specification

Contract testing

An OAS is like a contract because it is an agreement that needs to be honored, but how do you test a contract? Lots of API testing (e.g., unit testing) just checks to make sure specific endpoints give a nice 200 response code, which is important, but what happens when an API changes? Are you checking to make sure you are not breaking other services that rely on it?

Contract testing is writing tests that ensure an API or microservice meets the standards and definitions described in your contract. In contract testing, you don't have to write dozens and dozens of assertions for different properties, because you already have the contract—your OAS. It's useful for testing the accuracy of API implementations in server code, SDKs, client libraries, and even third-party APIs, which is especially helpful when other services rely on an API. This can lead to faster development, less breaking code changes, and more accurate implementations.

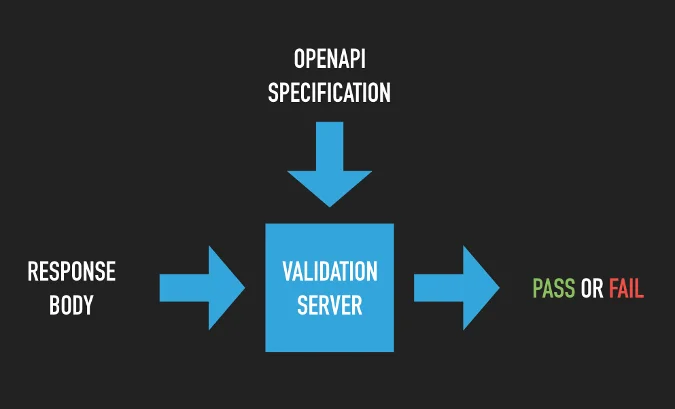

To contract-test your API, you need a server to act as a validation layer for incoming requests you are testing. The Prism server is one example of this. It is a performant, dependency-free server built specifically to work with web APIs on top of the OAS. It can validate your incoming API requests to make sure they match the contract within the specification.

One example of contract testing is JSON schema validation. You would test the entire nested response body to ensure every field matches the specification as the API was designed. This will ensure your API implementation is not breaking other services that rely on it.

It is important to note that contract testing is not a new idea. It started getting more attention in the early 2000s and has gone by a few different names, such as Abstract Test Cases. With the evolution of APIs and microservices, it is becoming a more common testing strategy alongside traditional methods.

The broken library

Let's make this a bit more real life. Imagine you have an API with a few different client libraries (sometimes referred to as SDKs). Someone contributing to one of these libraries works on a feature issue that adds functionality to match a new API operation. This functionality is greatly desired by the maintainers, and it gets a quick pull-request review and is merged into the library.

A week later, someone reports a bug in the library. They are not getting back the same JSON data structure as the API reference documentation says there should be for that operation. Another maintainer wonders, what happened? Did the API change? Is the reference documentation correct? Did something happen inside the library? Is the library user using it correctly?

After consulting the API implementation, the documentation, the bug reporter, and the library implementation, we find that the library implementation that was merged in was incorrect. It used a similar, but incorrect JSON data structure for the response of the API operation. How could this have been prevented? Contract testing!

One way you can contract-test API libraries is by including it in the pull-request review process. It could be automated within your continuous integration (CI) tool or run manually by the reviewer, which could have been done in the described example. Changes to a library that do not agree with the specification would never pass contract testing, ensuring the accuracy of your client libraries at all times.

Taylor Barnett will present Better API testing with the OpenAPI Specification at the 20th annual OSCON, July 16-19 in Portland, Ore.

1 Comment