The term "containers" is heavily overused. Also, depending on the context, it can mean different things to different people.

Traditional Linux containers are really just ordinary processes on a Linux system. These groups of processes are isolated from other groups of processes using resource constraints (control groups [cgroups]), Linux security constraints (Unix permissions, capabilities, SELinux, AppArmor, seccomp, etc.), and namespaces (PID, network, mount, etc.).

If you boot a modern Linux system and took a look at any process with cat /proc/PID/cgroup, you see that the process is in a cgroup. If you look at /proc/PID/status, you see capabilities. If you look at /proc/self/attr/current, you see SELinux labels. If you look at /proc/PID/ns, you see the list of namespaces the process is in. So, if you define a container as a process with resource constraints, Linux security constraints, and namespaces, by definition every process on a Linux system is in a container. This is why we often say Linux is containers, containers are Linux. Container runtimes are tools that modify these resource constraints, security, and namespaces and launch the container.

Docker introduced the concept of a container image, which is a standard TAR file that combines:

- Rootfs (container root filesystem): A directory on the system that looks like the standard root (

/) of the operating system. For example, a directory with/usr,/var,/home, etc. - JSON file (container configuration): Specifies how to run the rootfs; for example, what command or entrypoint to run in the rootfs when the container starts; environment variables to set for the container; the container's working directory; and a few other settings.

Docker "tar's up" the rootfs and the JSON file to create the base image. This enables you to install additional content on the rootfs, create a new JSON file, and tar the difference between the original image and the new image with the updated JSON file. This creates a layered image.

The definition of a container image was eventually standardized by the Open Container Initiative (OCI) standards body as the OCI Image Specification.

Tools used to create container images are called container image builders. Sometimes container engines perform this task, but several standalone tools are available that can build container images.

Docker took these container images (tarballs) and moved them to a web service from which they could be pulled, developed a protocol to pull them, and called the web service a container registry.

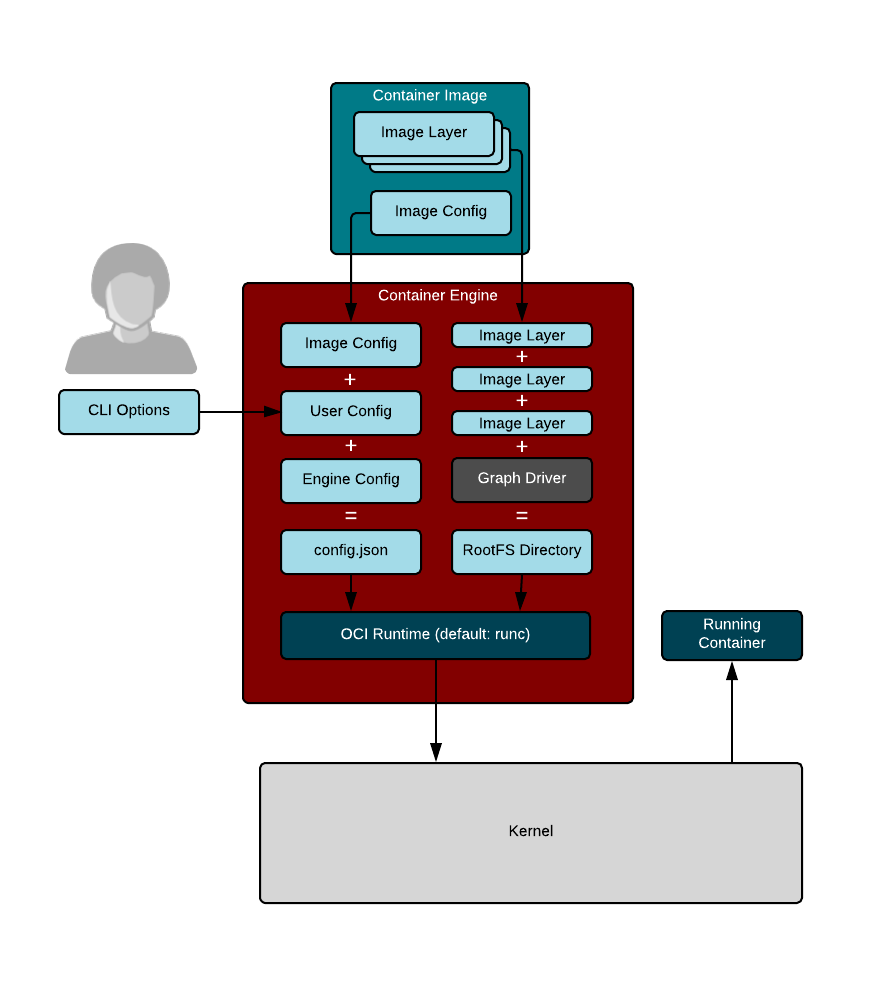

Container engines are programs that can pull container images from container registries and reassemble them onto container storage. Container engines also launch container runtimes (see below).

Linux container internals. Illustration by Scott McCarty. CC BY-SA 4.0

Container storage is usually a copy-on-write (COW) layered filesystem. When you pull down a container image from a container registry, you first need to untar the rootfs and place it on disk. If you have multiple layers that make up your image, each layer is downloaded and stored on a different layer on the COW filesystem. The COW filesystem allows each layer to be stored separately, which maximizes sharing for layered images. Container engines often support multiple types of container storage, including overlay, devicemapper, btrfs, aufs, and zfs.

After the container engine downloads the container image to container storage, it needs to create a container runtime configuration. The runtime configuration combines input from the caller/user along with the content of the container image specification. For example, the caller might want to specify modifications to a running container's security, add additional environment variables, or mount volumes to the container.

The layout of the container runtime configuration and the exploded rootfs have also been standardized by the OCI standards body as the OCI Runtime Specification.

Finally, the container engine launches a container runtime that reads the container runtime specification; modifies the Linux cgroups, Linux security constraints, and namespaces; and launches the container command to create the container's PID 1. At this point, the container engine can relay stdin/stdout back to the caller and control the container (e.g., stop, start, attach).

Note that many new container runtimes are being introduced to use different parts of Linux to isolate containers. People can now run containers using KVM separation (think mini virtual machines) or they can use other hypervisor strategies (like intercepting all system calls from processes in containers). Since we have a standard runtime specification, these tools can all be launched by the same container engines. Even Windows can use the OCI Runtime Specification for launching Windows containers.

At a much higher level are container orchestrators. Container orchestrators are tools used to coordinate the execution of containers on multiple different nodes. Container orchestrators talk to container engines to manage containers. Orchestrators tell the container engines to start containers and wire their networks together. Orchestrators can monitor the containers and launch additional containers as the load increases.

2 Comments