Trying to find out what's running on your machine—and which process is using up all your memory and making things slllooowwww—is a task served well by the utility top.

top is an extremely useful program that acts similar to Windows Task Manager or MacOS's Activity Monitor. Running top on your *nix machine will show you a live, running view of the process running on your system.

$ topDepending on which version of top you're running, you'll get something that looks like this:

top - 08:31:32 up 1 day, 4:09, 0 users, load average: 0.20, 0.12, 0.10

Tasks: 3 total, 1 running, 2 sleeping, 0 stopped, 0 zombie

%Cpu(s): 0.5 us, 0.3 sy, 0.0 ni, 99.2 id, 0.0 wa, 0.0 hi, 0.0 si, 0.0 st

KiB Mem: 4042284 total, 2523744 used, 1518540 free, 263776 buffers

KiB Swap: 1048572 total, 0 used, 1048572 free. 1804264 cached Mem

PID USER PR NI VIRT RES SHR S %CPU %MEM TIME+ COMMAND

1 root 20 0 21964 3632 3124 S 0.0 0.1 0:00.23 bash

193 root 20 0 123520 29636 8640 S 0.0 0.7 0:00.58 flask

195 root 20 0 23608 2724 2400 R 0.0 0.1 0:00.21 topYour version of top may look different from this, particularly in the columns that are displayed.

How to read the output

You can tell what you're running based on the output, but trying to interpret the results can be slightly confusing.

The first few lines contain a bunch of statistics (the details) followed by a table with a list of results (the list). Let's start with the latter.

The list

These are the processes that are running on the system. By default, they are ordered by CPU usage in descending order. This means the items at the top of the list are using more CPU resources and causing more load on your system. They are literally the "top" processes by resource usage. You have to admit, it's a clever name.

The COMMAND column on the far right reports the name of the process (the command you ran to start them). In this example, they are bash (a command interpreter we're running top in), flask (a web micro-framework written in Python), and top itself.

The other columns provide useful information about the processes:

PID: the process id, a unique identifier for addressing the processesUSER: the user running the processPR: the task's priorityNI: a nicer representation of the priorityVIRT: virtual memory size in KiB (kibibytes)*RES: resident memory size in KiB* (the "physical memory" and a subset of VIRT)SHR: shared memory size in KiB* (the "shared memory" and a subset of VIRT)S: process state, usually I=idle, R=running, S=sleeping, Z=zombie, T or t=stopped (there are also other, less common options)%CPU: Percentage of CPU usage since the last screen update%MEM: percentage ofRESmemory usage since the last screen updateTIME+: total CPU time used since the process startedCOMMAND: the command, as described above

*Knowing exactly what the VIRT, RES, and SHR values represent doesn't really matter in everyday operations. The important thing to know is that the process with the most VIRT is the process using the most memory. If you're in top because you're debugging why your computer feels like it's in a pool of molasses, the process with the largest VIRT number is the culprit. If you want to learn exactly what "shared" and "physical" memory mean, check out "Linux Memory Types" in the top manual.

And, yes, I did mean to type kibibytes, not kilobytes. The 1,024 value that you normally call a kilobyte is actually a kibibyte. The Greek kilo ("χίλιοι") means thousand and means 1,000 of something (e.g., a kilometer is a thousand meters, a kilogram is a thousand grams). Kibi is a portmanteau of kilo and byte, and it means 1,024 bytes (or 210). But, because words are hard to say, many people say kilobyte when they mean 1,024 bytes. All this means is top is trying to use the proper terms here, so just go with it. #themoreyouknow ?.

A note on screen updates:

Live screen updates are one of the objectively really cool things Linux programs can do. This means they can update their own display in real time, so they appear animated. Even though they're using text. So cool! In our case, the time between updates is important, because some of our statistics (%CPU and %MEM) are based on the value since the last screen update.

And because we're running in a persistent application, we can press key commands to make live changes to settings or configurations (instead of, say, closing the application and running the application again with a different command-line flag).

Typing h invokes the "help" screen, which also shows the default delay (the time between screen updates). By default, this value is (around) three seconds, but you can change it by typing d (presumably for "delay") or s (probably for "screen" or "seconds").

The details

Above the list of processes, there's a whole bunch of other useful information. Some of these details may look strange and confusing, but once you take some time to step through each one, you'll see they're very useful stats to pull up in a pinch.

The first row contains general system information

top: we're runningtop! Hitop!XX:YY:XX: the time, updated every time the screen updatesup(thenX day, YY:ZZ): the system's uptime, or how much time has passed since the system turned onload average(then three numbers): the system load over the last one, five, and 15 minutes, respectively

The second row (Tasks) shows information about the running tasks, and it's fairly self-explanatory. It shows the total number of processes and the number of running, sleeping, stopped, and zombie processes. This is literally a sum of the S (state) column described above.

The third row (%Cpu(s)) shows the CPU usage separated by types. The data are the values between screen refreshes. The values are:

us: user processessy: system processesni: nice user processesid: the CPU's idle time; a high idle time means there's not a lot going on otherwisewa: wait time, or time spent waiting for I/O completionhi: time spent waiting for hardware interruptssi: time spent waiting for software interruptsst: "time stolen from this VM by the hypervisor"

You can collapse the Tasks and %Cpu(s) rows by typing t (for "toggle").

The fourth (KiB Mem) and fifth rows (KiB Swap) provide information for memory and swap. These values are:

totalusedfree

But also:

- memory

buffers - swap

cached Mem

By default, they're listed in KiB, but pressing E (for "extend memory scaling") cycles through different values: kibibytes, mebibytes, gibibytes, tebibytes, pebibytes, and exbibytes. (That is, kilobytes, megabytes, gigabytes, terabytes, petabytes, and exabytes, but their "real names.")

The top user manual shows even more information about useful flags and configurations. To find the manual on your system, you can run man top. There are various websites that show an HTML rendering of the manual, but note that these may be for a different version of top.

Two top alternatives

You don't always have to use top to understand what's going on. Depending on your circumstances, other tools might help you diagnose issues, especially when you want a more graphical or specialized interface.

htop

htop is a lot like top, but it brings something extremely useful to the table: a graphical representation of CPU and memory use.

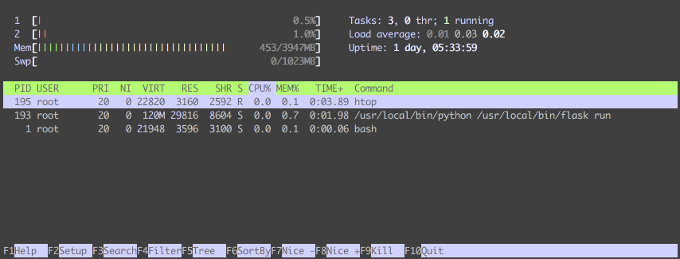

This is how the environment we examined in top looks in htop. The display is a lot simpler, but still rich in features.

Our task counts, load, uptime, and list of processes are still there, but we get a nifty, colorized, animated view of the CPU usage per core and a graph of memory usage.

Here's what the different colors mean (you can also get this information by pressing h for "help").

CPU task priorities or types:

- blue: low priority

- green: normal priority

- red: kernel tasks

- blue: virtualized tasks

- the value at end of the bar is the percentage of used CPU

Memory:

- green: used memory

- blue: buffered memory

- yellow: cached memory

- the values at the end of the bar show the used and total memory

If colors aren't useful for you, you can run htop -C to disable them; instead htop will use different symbols to separate the CPU and memory types.

At the bottom, there's a useful display of active function keys that you can use to do things like filter results or change the sort order. Try out some of the commands to see what they do. Just be careful when trying out F9. This will bring up a list of signals that will kill (i.e., stop) a process. I would suggest exploring these options outside of a production environment.

The author of htop, Hisham Muhammad (and yes, it's called htop after Hisham) presented a lightning talk about htop at FOSDEM 2018 in February. He explained how htop not only has neat graphics, but also surfaces more modern statistical information about processes that older monitoring utilities (like top) don't.

You can read more about htop on the manual page or the htop website. (Warning: the website contains an animated background of htop.)

docker stats

If you're working with Docker, you can run docker stats to generate a context-rich representation of what your containers are doing.

This can be more helpful than top because, instead of separating by processes, you are separating by container. This is especially useful when a container is slow, as seeing which container is using the most resources is quicker than running top and trying to map the process to the container.

The above explanations of acronyms and descriptors in top and htop should make it easy to understand the ones in docker stats. However, the docker stats documentation provides helpful descriptions of each column.

1 Comment