Sysadmins have many tools to view and manage running processes. For me, these primarily used to be top, atop, and htop. A few years ago, I found Glances, a tool that displays information that none of my other favorites do. All of these tools monitor CPU and memory usage, and most of them list information about running processes (at the very least). However, Glances also monitors filesystem I/O, network I/O, and sensor readouts that can display CPU and other hardware temperatures as well as fan speeds and disk usage by hardware device and logical volume.

Glances

I mentioned Glances in my article 4 open source tools for Linux system monitoring, but I will delve into it more deeply in this article. If you read my previous article, some of this information may be familiar, but you should also find some new things here.

Glances is cross-platform because it is written in Python. It can be installed on Windows and other hosts with current versions of Python installed. Most Linux distributions (Fedora in my case) have Glances in their repositories. If not, or if you are using a different operating system (such as Windows), or you just want to get it right from the source, you can find instructions for downloading and installing it in Glances' GitHub repo.

I suggest running Glances on a test machine while you try the commands in this article. If you don't have a physical host available for testing, you can explore Glances on a virtual machine (VM), but you won't see the hardware sensors section; after all, a VM has no real hardware.

To start Glances on a Linux host, open a terminal session and enter the command glances.

Glances has three main sections—Summary, Process, and Alerts—as well as a sidebar. I'll explore them and other details for using Glances now.

Summary section

In its top few lines, Glances' Summary section contains much of the same information as you'll find in other monitors' summary sections. If you have enough horizontal space in your terminal, Glances can show CPU usage with both a bar graph and a numeric indicator; otherwise it will show only the number.

I like Glances' Summary section better than the ones in other monitors (like top); I think it provides the right information in an easily understandable format.

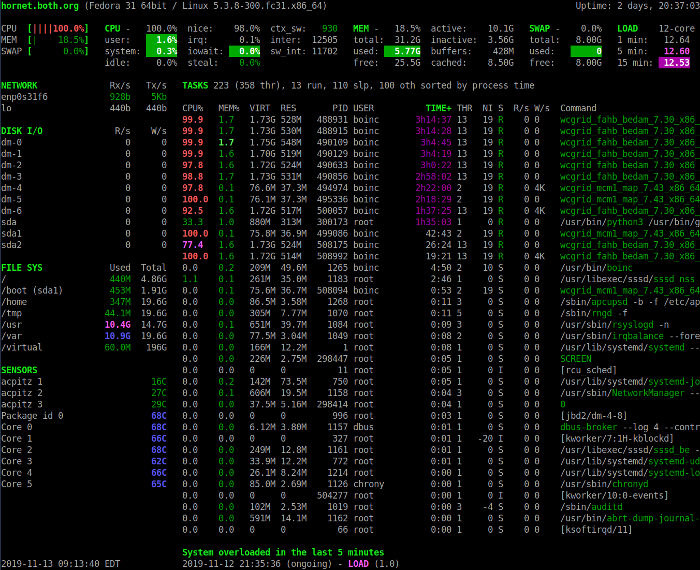

The Glances display on a busy Linux host. In the interest of clarity, not all possible displays are shown in the left sidebar.

The Summary section above provides an overview of the system's status. The first line shows the hostname, the Linux distribution, the kernel version, and the system uptime.

The next four lines display CPU, memory usage, swap, and load statistics. The left column displays the percentages of CPU, memory, and swap space that are in use. It also shows the combined statistics for all CPUs present in the system.

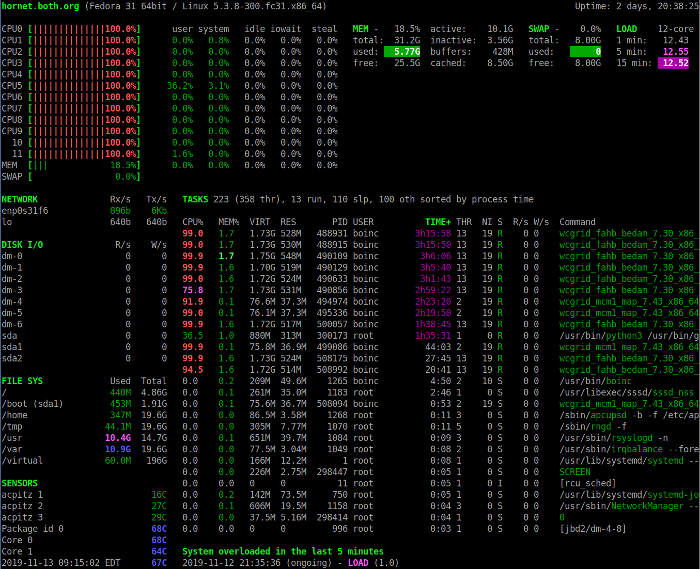

Press the 1 key to toggle between the consolidated CPU usage display and the display of the individual CPUs. The following image shows the Glances display with individual CPU statistics.

Glances showing the individual CPU statistics.

This view includes some additional CPU statistics. In either display mode, the descriptions of the CPU usage fields can help you interpret the data displayed in the CPU section. Notice that CPUs are numbered starting at 0 (Zero).

| CPU | This is the current CPU usage as a percentage of the total available. |

| user | These are the applications and other programs running in user space, i.e., not in the kernel. |

| system | These are kernel-level functions. It does not include CPU time taken by the kernel itself, just the kernel system calls. |

| idle | This is the idle time, i.e., time not used by any running process. |

| nice | This is the time used by processes that are running at a positive, nice level. |

| irq | These are the interrupt requests that take CPU time. |

| iowait | These are CPU cycles that are spent waiting for I/O to occur—this is wasted CPU time. |

| steal | The percentage of CPU cycles that a virtual CPU waits for a real CPU while the hypervisor is servicing another virtual processor. |

| ctx-sw | These are the number of context switches per second; it represents the number of times per second that the CPU switches from running one process to another. |

| inter | This is the number of hardware interrupts per second. A hardware interrupt occurs when a hardware device, such as a hard drive, tells a CPU that it has completed a data transfer or that a network interface card is ready to accept more data. |

| sw_int | Software interrupts tell the CPU that some requested task has completed or that the software is ready for something. These tend to be more common in kernel-level software. |

About nice numbers

Nice numbers are the mechanism used by administrators to affect the priority of a process. It is not possible to change the priority of a process directly, but changing the nice number can modify the results of the kernel scheduler’s priority setting algorithm. Nice numbers run from -20 to +19 where higher numbers are nicer. The default nice number is 0 and the default priority is 20. Setting the nice number higher than zero increases the priority number somewhat, thus making the process nicer and therefore less greedy of CPU cycles. Setting the nice number to a more negative number results in a lower priority number making the process less nice. Nice numbers can be changed using the renice command or from within top, atop, and htop.

Memory

The Memory portion of the Summary section contains statistics about memory usage.

| MEM | This shows the memory usage as a percent of the total amount available. |

| total | This is the total amount of RAM memory installed in the host, less any amount assigned to the display adapter. |

| used | This is the total amount of memory in use by the system and application programs but not including cache or buffers. |

| free | This is the amount of free memory. |

| active | This is the amount of actively used memory—inactive memory is subject to swapping to disk should the need arise. |

| inactive | This is memory that is in use but that has not been accessed for some time. |

| buffers | This is memory that is used for buffer space; it is usually used by communications and I/O such as networking. The data is received and stored until the software can retrieve it for use or it can be sent to a storage device or transmitted out to the network. |

| cached | This is the memory used to store data for disk transfer until it can be used by a program or stored to disk. |

The Swap section is self-explanatory if you understand a bit about swap space and how it works. This shows how much total swap space is available, how much is used, and how much is left.

The Load part of the Summary section displays the one-, five-, and 15-minute load averages.

You can use the numeric keys 1, 3, 4, and 5 to alter your view of the data in this section. The 2 key toggles the left sidebar on and off.

More about load averages

Load averages are commonly misunderstood, even though they are a key criterion for measuring CPU usage. But what does it really mean when I say that the one- (or five- or 10-) minute load average is 4.04, for example? Load average can be considered a measure of demand for the CPU; it is a number that represents the average number of instructions waiting for CPU time, so it is a true measure of CPU performance.

For example, a fully utilized single-processor system CPU would have a load average of 1. This means that the CPU is keeping up exactly with demand; in other words, it has perfect utilization. A load average of less than 1 means the CPU is underutilized, and a load average greater than 1 means the CPU is overutilized and that there is pent-up, unsatisfied demand. For example, a load average of 1.5 in a single-CPU system indicates that one-third of the CPU instructions must wait to be executed until the preceding one has completed.

This is also true for multiple processors. If a four-CPU system has a load average of 4, then it has perfect utilization. If it has a load average of 3.24, for example, then three of its processors are fully utilized, and one is utilized at about 24%. In the example above, a four-CPU system has a one-minute load average of 4.04, meaning there is no remaining capacity among the four CPUs, and a few instructions are forced to wait. A perfectly utilized four-CPU system would show a load average of 4.00, meaning that the system is fully loaded but not overloaded.

The optimum load average condition is for the load average to equal the total number of CPUs in a system. That would mean that every CPU is fully utilized, and no instruction must be forced to wait. But reality is messy, and optimum conditions are seldom met. If a host were running at 100% utilization, this would not allow for spikes in CPU load requirements.

The longer-term load averages indicate overall utilization trends.

Linux Journal published an excellent article about load averages, the theory, the math behind them, and how to interpret them, in its December 1, 2006, issue. Unfortunately, Linux Journal has ceased publication, and its archives are no longer available directly, so the link is to a third-party archive.

Finding CPU hogs

One of the reasons for using a tool like Glances is to find processes that are taking up too much CPU time. Open a new terminal session (different from the one running Glances), and enter and start the following CPU-hogging Bash program.

X=0;while [ 1 ];do echo $X;X=$((X+1));doneThis program is a CPU hog and will use up every available CPU cycle. Allow it to run while you finish this article and experiment with Glances. It will provide you with an idea of what a program that hogs CPU cycles looks like. Be sure to observe the effects on the load averages over time, as well as the cumulative time in the TIME+ column for this process.

Process section

The Process section displays standard information about each process that is running. Depending upon the viewing mode and the size of the terminal screen, different columns of information will be displayed for the running processes. The default mode with a wide-enough terminal displays the columns listed below. The columns that are displayed change automatically if the terminal screen is resized. The following columns are typically displayed for each process from left to right.

| CPU% | This is the amount of CPU time as a percentage of a single core. For example, 98% represents 98% of the available CPU cycles for a single core. Multiple processes can show up to 100% CPU usage. |

| MEM% | This is the amount of RAM memory used by the process as a percentage of the total virtual memory in the host. |

| VIRT | This is the amount of virtual memory used by the process in human-readable format, such as 12M for 12 megabytes. |

| RES | This refers to the amount of physical (resident) memory used by the process. Again, this is in human-readable format, with an indicator of K, M, or G, to specify kilobytes, megabytes, or gigabytes. |

| PID | Every process has an identification number, called the PID. This number can be used in commands, such as renice and kill, to manage the process. Remember that the kill utility can send signals to another process besides the “kill” signal. |

| USER | This is the name of the user that owns the process. |

| TIME+ | This indicates the cumulative amount of CPU time accrued by the process since it started. |

| THR | This is the total number of threads currently running for this process. |

| NI | This is the nice number of the process. |

| S | This is the current status; it can be (R)unning, (S)leeping, (I)dle, T or t when the process is stopped during a debugging trace, or (Z)ombie. A zombie is a process that has been killed but has not completely died, so it continues to consume some system resources, such as RAM. |

| R/s and W/s | These are the disk reads and writes per second. |

| Command | This is the command used to start the process. |

Glances usually determines the default sort column automatically. Processes can be sorted automatically (a), or by CPU (c), memory (m), name (p), user (u), I/O rate (i), or time (t). Processes are automatically sorted by the most-used resource. In the images above, the TIME+ column is highlighted.

Alerts section

Glances also shows warnings and critical alerts, including the time and duration of the event, at the bottom of the screen. This can be helpful when you're attempting to diagnose problems and cannot stare at the screen for hours at a time. These alert logs can be toggled on or off with the l (lower-case L) key, warnings can be cleared with the w key, while alerts and warnings can all be cleared with x.

Sidebar

Glances has a very nice sidebar on the left that displays information that is not available in top or htop. While atop displays some of this data, Glances is the only monitor that displays data about sensors. After all, sometimes it is nice to see the temperatures inside your computer.

The individual modules, disk, filesystem, network, and sensors can be toggled on and off using the d, f, n, and s keys, respectively. The entire sidebar can be toggled using 2. Docker stats can be displayed in the sidebar with D.

Note that hardware sensors are not displayed when Glances is running on a virtual machine.

Getting help

You can get help by pressing the h key; dismiss the help page by pressing h again. The Help page is rather terse, but it does show the available interactive options and how to turn them on and off. The man page has terse explanations of the options that can be used when launching Glances.

You can press q or Esc to exit Glances.

Configuration

Glances does not require a configuration file to work properly. If you choose to have one, the system-wide instance of the configuration file will be located in /etc/glances/glances.conf. Individual users can have a local instance at ~/.config/glances/glances.conf, which will override the global configuration. The primary purpose of these configuration files is to set thresholds for warnings and critical alerts. You can also specify whether certain modules are displayed by default or not.

The file /usr/local/share/doc/glances/README.rst contains additional useful information, including optional Python modules you can install to support some optional Glances features.

Command-line options

Glances provides command-line options that allow it to start up in specific viewing modes. For example, the command glances -2 starts the program with the left sidebar disabled.

Remote and more

By starting it in server mode, you can use Glances to monitor remote hosts:

[root@testvm1 ~]# glances -sYou can then connect to the server from the client with:

[root@testvm2 ~]# glances -c @testvm1Glances can show a list of Glances servers along with a summary of their activity. It also has a web interface so you can monitor remote Glances servers from a browser. Recent versions of Glances can also display Docker statistics.

There are also pluggable modules for Glances that provide measurement data not available in the base program.

Limitations

Although Glances can monitor many aspects of a host, it cannot manage processes. It cannot change the nice number of a process nor kill one, as top and htop can. Glances is not an interactive tool. It is used strictly for monitoring. External tools like kill and renice can be used to manage processes.

Glances can only show the processes that are taking the majority of the resource specified, such as CPU time, in the available space. If there is room to list just 10 processes, that is all you will be able to see. Glances does not provide scrolling or reverse-sort options that would enable you to see any other than the top X processes.

The impact of measurement

The observer effect is a physics theory that states, "simply observing a situation or phenomenon necessarily changes that phenomenon." This is also true when measuring Linux system performance.

Merely using a monitoring tool alters the system's use of resources, including memory and CPU time. The top utility and most other monitors use perhaps 2% tor 3% of a system's CPU time. The Glances utility has much more impact than the others; it usually uses between 10% and 20% of CPU time, and I have seen it use as much as 40% of one CPU in a very large and active system with 32 CPUs. That is a lot, so consider its impact when you think about using Glances as your monitor.

My personal opinion is that this is a small price to pay when you need the capabilities of Glances.

Summary

Despite its lack of interactive capabilities, such as the ability to renice or kill processes, and its high CPU load, I find Glances to be a very useful tool. The complete Glances documentation is available on the internet, and the Glances man page has startup options and interactive command information.

Parts of this article are based on David Both's new book, Using and Administering Linux: Volume 2 – Zero to SysAdmin: Advanced Topics.

3 Comments