Vagrant describes itself as "a tool for building and managing virtual machine environments in a single workflow. With an easy-to-use workflow and focus on automation, Vagrant lowers development environment setup time, increases production parity, and makes the 'works on my machine' excuse a relic of the past."

Vagrant works with a standard format for documenting an environment, called a Vagrantfile. According to Vagrant's website:

"The primary function of the Vagrantfile is to describe the type of machine required for a project, and how to configure and provision these machines. Vagrantfiles are called Vagrantfiles because the actual literal filename for the file is Vagrantfile (casing does not matter unless your file system is running in a strict case sensitive mode)."

Vagrant is essentially a wrapper to allow for repeatable virtual machine management, but it does not run VMs itself. This tutorial will use VirtualBox as that environment manager, though Hyper-V and Docker also work by default. Check out Vagrant's documentation to learn how to use a different provider for this tutorial.

Build a Vagrantfile

This tutorial works through an example application for a simple Hello World page inside a Ruby on Rails (Rails for short) web app. Before you begin, install the following (if you haven't already):

- Vagrant

- VirtualBox

- Ruby on Rails

- An editing environment, like Atom or Notepad++

If you're on Fedora and prefer using the command line, there is an excellent Fedora tutorial, and there's a similarly helpful tutorial for Windows using Chocolatey. After everything is installed, open your terminal and create a new directory to work in. You can put your directory wherever you like; I prefer to use a folder under my user account:

$ mkdir -p ~/Development/Rails_app

$ cd ~/Development/Rails_app

$ vagrant init

A `Vagrantfile` has been placed in this directory. You are now

ready to `vagrant up` your first virtual environment! Please read

the comments in the Vagrantfile as well as documentation on

`vagrantup.com` for more information on using Vagrant.This creates a Vagrantfile with the default configuration information written in Ruby syntax. Look at line 15:

config.vm.box = "base"This indicates that Vagrant will use a default operating system image it hosts called base, which you don't have yet. Confirm that by running box list:

$ vagrant box list

There are no installed boxes! Use `vagrant box add` to add some.If you try to start your environment using the up command, it will fail, because Vagrant expects an OS called base to exist locally. Switch to the most commonly used environment, bento/ubuntu-16.04, then try to spin up your environment. Change the config.vm.box line in your Vagrantfile to:

config.vm.box = "centos/7"And now you can run the most satisfying command in virtual machine history:

$ vagrant up

Bringing machine 'default' up with 'libvirt' provider...

==> default: Box 'centos/7' could not be found. Attempting to find and install...

default: Box Provider: libvirt

default: Box Version: >= 0

==> default: Loading metadata for box 'centos/7'

default: URL: https://vagrantcloud.com/centos/7

==> default: Adding box 'centos/7' (v1905.1) for provider: libvirt

default: Downloading: https://vagrantcloud.com/centos/boxes/7/versions/1905.1/providers/libvirt.box

default: Download redirected to host: cloud.centos.org

...Here is why this is so nice. This tutorial sets up a small website, but if you had a larger website and needed to check whether the frontend looks right, your playbook file and copy-over files would allow you to see your changes. If you have small applications you want to test quickly—without doing an entire Docker image build or logging into a server—this local testing is good for quick checks and repairs. If you're working within hardware, this will make it easy to see if the application will work within your operating system, and it allows you to know which dependencies you need. In the end, it makes for easier deployment and faster testing than doing a from-scratch continuous integration and deployment (CI/CD) to a test server, and it provides quicker access and more control.

The reason this is so cool can be explained in one simple sentence: You now have local automation. It also allows you to gather a larger breadth of knowledge behind Ansible and headless server deployments.

Verify Vagrant worked correctly

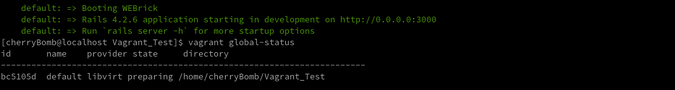

One way to determine whether this finished properly is seeing a bunch of green text and the words rails server -h for startup options. This means the web app has started and is running.

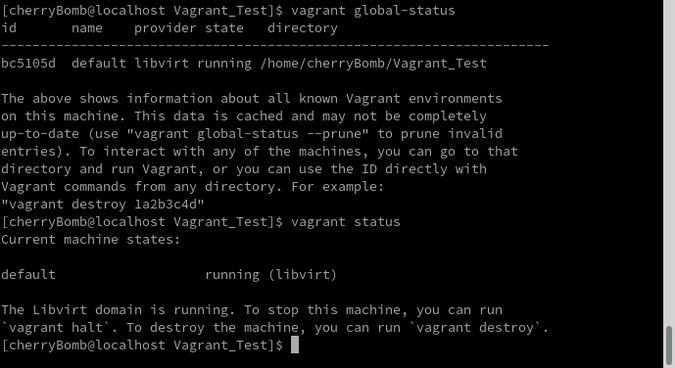

But you want to use vagrant global-status as well as vagrant status.

The vagrant status command checks the machine states that originate in the current directory. So, if you have a VM up and running, it will show as up and running. If it is broken in any way, it will display a message with an error and some logs when you run vagrant up. If some machines are down, they will also show as not running or shut down.

However, the vagrant global-status command can give the status of multiple environments created in Vagrant. So, if you split the environments for different VM types or storage types, this command gives you an option to see everything in all the environments you've created.

Customize the Vagrant configuration

The machine settings have multiple config.vm options. This tutorial will use the networking option to allow port forwarding. Port forwarding allows you to access a network port in our virtual environment as if it was a local port via a special local network. This means traffic is allowed to see the one thing you allow on this server; in this case, it's a tiny frontend webpage.

The main reason this matters is for security. Limiting traffic can prevent bad actors and traffic overflow. The way this is built, you can't log into this server unless you configure it as such. This also means no one else can SSH in or see anything except the one little frontend webpage.

Before moving on, remove the VM so you can start over by running vagrant destroy:

$ vagrant destroy

default: Are you sure you want to destroy the 'default' VM? [y/N] y

==> default: Removing domain...To include port forwarding, add this in the next config line:

Vagrant.configure("2") do |config|

config.vm.box = "bento/ubuntu-16.04"

config.vm.network "forwarded_port", guest: 3000, host: 9090

endSave the file and run:

vagrant upYou now have a VM that forwards port 3000 out to the open world as 9090. You should now be able to go to 127.0.0.1:9090 on your web browser and see nothing but a plain white page.

Run vagrant destroy again to remove the VM so you can start over.

Provision Vagrant with Ansible and scripts

While base boxes offer a good starting point, it's common to customize a VM during the provisioning process, and you can use multiple provisioning tactics. To follow along, download the playbook and script.

This example uses Ansible to set up a basic install of the Ruby on Rails web framework. Then, it adds an extra shell script to configure the web app's welcome page to say: Hello World, Sorry for the Delay. (The purpose of this message is because this build takes a long time and people may become frustrated by the delay.)

The following Vagrantfile reflects Ansible and a playbook running locally on my machine, so it will differ from yours. You can read about using Ansible with Vagrant in Vagrant's docs.

Vagrant.configure("2") do |config|

config.vm.box = "bento/ubuntu-16.04"

config.vm.network "forwarded_port", guest: 3000, host: 9090

####### Provision #######

config.vm.provision "ansible_local" do |ansible|

ansible.playbook = "prov/playbook.yml"

ansible.verbose = true

config.vm.provision "shell", path: "script.sh"

end

endAfter saving the file, run my favorite command:

vagrant upYou now have a VM up and running with Rails, and when you enter 127.0.0.1:9090 in your web browser, you see a webpage that says: Hello World, Sorry for the Delay.

Now that you have all this background, you can try to build your own script.

Final notes

Vagrant is fairly easy to work with and has abundant documentation to help you along the way. It's is a great tool if you're looking to work with code in a small staging or development environment; any destruction is a non-issue because the environment itself is disposable.

Want to give it a try? Take a look at my repo.

Comments are closed.