Do you recognize the following scenario? I do, because a manager once stifled my passion and innovation to the point I was anxious to make decisions, take risks, and focus on what's important: "uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it" (Agile Manifesto, 2001).

Developer: "The UX hypothesis failed. Users did not respond well to the new navigation experience, resulting in 80% of users switching back to the classic navigation."

Manager: "This is really bad! How is this possible? We need to fix this because I'm not sure that our stakeholders want to hear about your failure."

Here is a different, more powerful response.

Leader: "What are the probable causes for our hypothesis failing and how can we improve the user experience? Let us analyze and share our remediation plan with our stakeholders."

It is all about the tone that centers on a constructive and blameless mindset.

There are various types of fear that paralyze people, who then infect their team. Fearful that nothing is ever enough, pushing themselves to do more and more, viewing feedback as unfavorable, and often burning themselves out. They work hard, not smart—delivering volume, not value.

Others fear being judged, compare themselves with others, and shy away from accountability. They seldom share their knowledge, passion, or work; instead of vibrant collaboration, they find themselves wandering through a ghost ship filled with skeletons and foul fish.

"The only thing we have to fear is fear itself." – Franklin D. Roosevelt

Fear of failure is rife in many organizations, especially those that have embarked on a digital transformation journey. It's caused by the undesirability of failure, knowledge of repercussions, and lack of appetite for validated learning.

This is a strange phenomenon because when we look at the Manifesto for Agile Software Development, we notice references to "customer collaboration" and "responding to change." Lean thinking promotes principles such as "optimize the whole," "eliminate waste," "create knowledge," "build quality in," and "respect people." Also, two of the Kanban principles mention "visualize work" and "continuous improvement."

I have a hypothesis:

"I believe an organization will embrace failure if we elaborate the benefit of failure in the context of software engineering to all stakeholders."

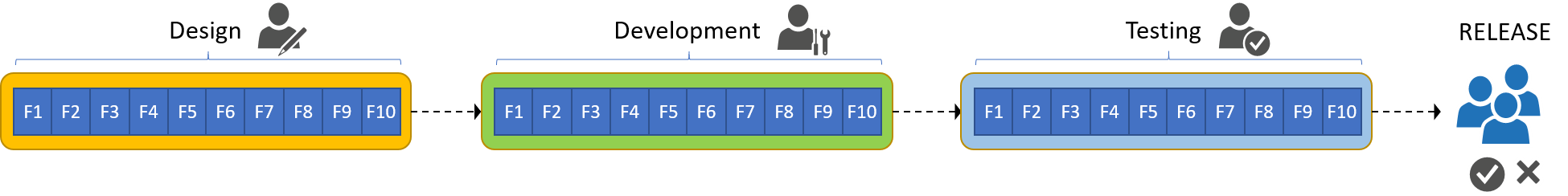

Let's look at a traditional software development lifecycle that strives for quality, is based on strict processes, and is sensitive to failure. We design, develop, and test all features in sequence. The solution is released to the customer when QA and security give us the "thumbs up," followed by a happy user (success) or unhappy user (failure).

With the traditional model, we have one opportunity to fail or succeed. This is probably an effective model if we are building a sensitive product such as a multimillion-dollar rocket or aircraft. Context is important!

Now let's look at a more modern software development lifecycle that strives for quality and embraces failure. We design, build, and test and release a limited release to our users for preview. We get feedback. If the user is happy (success), we move to the next feature. If the user is unhappy (failure), we either improve or scrap the feature based on validated feedback.

Note that we have a minimum of one opportunity to fail per feature, giving us a minimum of 10 opportunities to improve our product, based on validated user feedback, before we release the same product. Essentially, this modern approach is a repetition of the traditional approach, but it's broken down into smaller release cycles. We cannot reduce the effort to design, develop, and test our features, but we can learn and improve the process. You can take this software engineering process a few steps further.

- Continuous delivery (CD) aims to deliver software in short cycles and releases features reliably, one at a time, at a click of a button by the business or user.

- Test-driven development (TDD) is a software engineering approach that creates many debates among stakeholders in business, development, and quality assurance. It relies on short and repetitive development cycles, each one crafting test cases based on requirements, failing, and developing software to pass the test cases.

- Hypothesis-driven development (HDD) is based on a series of experiments to validate or disprove a hypothesis in a complex problem domain where we have unknown unknowns. When the hypothesis fails, we pivot. When it passes, we focus on the next experiment. Like TDD, it is based on very short repetitions to explore and react on validated learning.

Yes, I am confident that failure is not bad. In fact, it is an enabler for innovation and continuous learning. It is important to emphasize that we need to embrace failure in the form of fail fast, which means that we slice our product into small units of work that can be developed and delivered as value, quickly and reliably. When we fail, the waste and impact must be minimized, and the validated learning maximized.

To avoid the fear of failure among engineers, all stakeholders in an organization need to trust the engineering process and embrace failure. The best antidote is leaders who are supportive and inspiring, along with having a collective blameless mindset to plan, prioritize, build, release, and support. We should not be reckless or oblivious of the impact of failure, especially when it impacts investors or livelihoods.

We cannot be afraid of failure when we're developing software. Otherwise, we will stifle innovation and evolution, which in turn suffocates the union of people, process, and continuous delivery of value, key ingredients of DevOps as defined by Donovan Brown:

"DevOps is the union of people, process, and products to enable continuous delivery of value to our end users."

Special thanks to Anton Teterine and Alex Bunardzic for sharing their perspectives on fear.

5 Comments