There are many different ways to solve problems in computing. You might "brute force" your way to a solution by calculating as many possibilities as you can, or you might take a procedural approach and carefully establish the known factors that influence the correct answer. In constraint programming, a problem is viewed as a series of limitations on what could possibly be a valid solution. This paradigm can be applied to effectively solve a group of problems that can be translated to variables and constraints or represented as a mathematic equation. In this way, it is related to the Constraint Satisfaction Problem (CSP).

Using a declarative programming style, it describes a general model with certain properties. In contrast to the imperative style, it doesn't tell how to achieve something, but rather what to achieve. Instead of defining a set of instructions with only one obvious way to compute values, constraint programming declares relationships between variables within constraints. A final model makes it possible to compute the values of variables regardless of direction or changes. Thus, any change in the value of one variable affects the whole system (i.e., all other variables), and to satisfy defined constraints, it leads to recomputing the other values.

As an example, let's take Pythagoras' theorem: a² + b² = c². The constraint is represented by this equation, which has three variables (a, b, and c), and each has a domain (non-negative). Using the imperative programming style, to compute any of the variables if we have the other two, we would need to create three different functions (because each variable is computed by a different equation):

- c = √(a² + b²)

- a = √(c² - b²)

- b = √(c² - a²)

These functions satisfy the main constraint, and to check domains, each function should validate the input. Moreover, at least one more function would be needed for choosing an appropriate function according to the provided variables. This is one of the possible solutions:

def pythagoras(*, a=None, b=None, c=None):

''' Computes a side of a right triangle '''

# Validate

if len([i for i in (a, b, c) if i is None or i <= 0]) != 1:

raise SystemExit("ERROR: you need to define any of two non-negative variables")

# Compute

if a is None:

return (c**2 - b**2)**0.5

elif b is None:

return (c**2 - a**2)**0.5

else:

return (a**2 + b**2)**0.5To see the difference with the constraint programming approach, I'll show an example of a "problem" with four variables and a constraint that is not represented by a straight mathematic equation. This is a converter that can change characters' cases (lower-case to/from capital/upper-case) and return the ASCII codes for each. Hence, at any time, the converter is aware of all four values and reacts immediately to any changes. The idea of creating this example was fully inspired by John DeNero's Fahrenheit-Celsius converter.

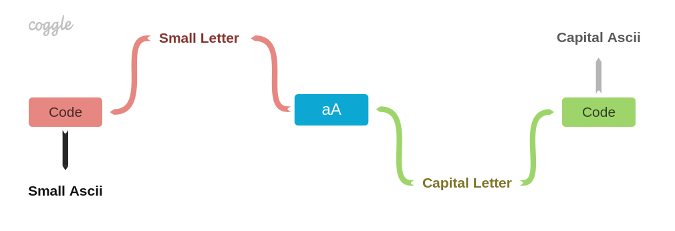

Here is a diagram of a constraint system:

The represented "problem" is translated into a constraint system that consists of nodes (constraints) and connectors (variables). Connectors provide an interface for getting and setting values. They also check the variables' domains. When one value changes, that particular connector notifies all its connected nodes about the change. Nodes, in turn, satisfy constraints, calculate new values, and propagate them to other connectors across the system by "asking" them to set a new value. Propagation is done using the message-passing technique that means connectors and nodes get messages (synchronously) and react accordingly. For instance, if the system gets the A letter on the "capital letter" connector, the other three connectors provide an appropriate result according to the defined constraint on the nodes: 97, a, and 65. It's not allowed to set any other lower-case letters (e.g., b) on that connector because each connector has its own domain.

When all connectors are linked to nodes, which are defined by constraints, the system is fully set and ready to get values on any of four connectors. Once it's set, the system automatically calculates and sets values on the rest of the connectors. There is no need to check what variable was set and which functions should be called, as is required in the imperative approach—that is relatively easy to achieve with a few variables but gets interesting in case of tens or more.

How it works

The full source code is available in my GitHub repo. I'll dig a little bit into the details to explain how the system is built.

First, define the connectors by giving them names and setting domains as a function of one argument:

import constraint_programming as cp

small_ascii = cp.connector('Small Ascii', lambda x: x >= 97 and x <= 122)

small_letter = cp.connector('Small Letter', lambda x: x >= 'a' and x <= 'z')

capital_ascii = cp.connector('Capital Ascii', lambda x: x >= 65 and x <= 90)

capital_letter = cp.connector('Capital Letter', lambda x: x >= 'A' and x <= 'Z')Second, link these connectors to nodes. There are two types: code (translates letters back and forth to ASCII codes) and aA (translates small letters to capital and back):

code(small_letter, small_ascii)

code(capital_letter, capital_ascii)

aA(small_letter, capital_letter)These two nodes differ in which functions should be called, but they are derived from a general constraint function:

def code(conn1, conn2):

return cp.constraint(conn1, conn2, ord, chr)

def aA(conn1, conn2):

return cp.constraint(conn1, conn2, str.upper, str.lower)Each node has only two connectors. If there is an update on a first connector, then a first function is called to calculate the value of another connector (variable). The same happens if a second connector's value changes. For example, if the code node gets A on the conn1 connector, then the function ord will be used to get its ASCII code. And, the other way around, if the aA node gets A on the conn2 connector, then it needs to use the str.lower function to get the correct small letter on the conn1. Every node is responsible for computing new values and "sending" a message to another connector that there is a new value to set. This message is conveyed with the name of a node that is asking to set a new value and also a new value.

def set_value(src_constr, value):

if (not domain is None) and (not domain(value)):

raise ValueOutOfDomain(link, value)

link['value'] = value

for constraint in constraints:

if constraint is not src_constr:

constraint['update'](link)When a connector receives the set message, it runs the set_value function to check a domain, sets a new value, and sends the "update" message to another node. It is just a notification that the value on that connector has changed.

def update(src_conn):

if src_conn is conn1:

conn2['set'](node, constr1(conn1['value']))

else:

conn1['set'](node, constr2(conn2['value']))Then, the notified node requests this new value on the connector, computes a new value for another connector, and so on until the whole system changes. That's how the propagation works.

But how does the message passing happen? It is implemented as accessing keys of dictionaries. Both functions (connector and constraint) return a dispatch dictionary. Such a dictionary contains messages as keys and closures as values. By accessing a key, let's say, set, a dictionary returns the function set_value (closure) that has access to all local names of the "connector" function.

# A dispatch dictionary

link = { 'name': name,

'value': None,

'connect': connect,

'set': set_value,

'constraints': get_constraints }

return linkHaving a dictionary as a return value makes it possible to create multiple closures (functions) with access to the same local state to operate on. Then these closures are callable by using keys as a type of message.

Why use Constraint programming?

Constraint programming can give you a new perspective to difficult problems. It's not something you can use in every situation, but it may well open new opportunities for solutions in certain situations. If you find yourself up against an equation that seems difficult to reliably solve in code, try looking at it from a different angle. If the angle that seems to work best is constraint programming, you now have an example of how it can be implemented.

This article was originally published on Oleksii Tsvietnov's blog and is reprinted with his permission.

Comments are closed.