The third article in this series demonstrated how to use failure and unit testing to develop better code.

While it seemed that the journey was over with a successful sample Internet of Things (IoT) application to control a cat door, experienced programmers know that solutions need mutation.

What's mutation testing?

Mutation testing is the process of iterating through each line of implemented code, mutating that line, then running unit tests and checking if the mutation broke the expectations. If it hasn't, you have created a surviving mutant.

Surviving mutants are always an alarming issue that points to potentially risky areas in a codebase. As soon as you catch a surviving mutant, you must kill it. And the only way to kill a surviving mutant is to create additional descriptions—new unit tests that describe your expectations regarding the output of your function or module. In the end, you deliver a lean, mean solution that is airtight and guarantees no pesky bugs or defects are lurking in your codebase.

If you leave surviving mutants to kick around and proliferate, live long, and prosper, then you are creating the much dreaded technical debt. On the other hand, if any unit test complains that the temporarily mutated line of code produces output that's different from the expected output, the mutant has been killed.

Installing Stryker

The quickest way to try mutation testing is to leverage a dedicated framework. This example uses Stryker.

To install Stryker, go to the command line and run:

$ dotnet tool install -g dotnet-strykerTo run Stryker, navigate to the unittest folder and type:

$ dotnet-strykerHere is Stryker's report on the quality of our solution:

14 mutants have been created. Each mutant will now be tested, this could take a while.

Tests progress | 14/14 | 100% | ~0m 00s |

Killed : 13

Survived : 1

Timeout : 0

All mutants have been tested, and your mutation score has been calculated

- \app [13/14 (92.86%)]

[...]The report says:

- Stryker created 14 mutants

- Stryker saw 13 mutants were killed by the unit tests

- Stryker saw one mutant survive the onslaught of the unit tests

- Stryker calculated that the existing codebase contains 92.86% of code that serves the expectations

- Stryker calculated that 7.14% of the codebase contains code that does not serve the expectations

Overall, Stryker claims that the application assembled in the first three articles in this series failed to produce a reliable solution.

How to kill a mutant

When software developers encounter surviving mutants, they typically reach for the implemented code and look for ways to modify it. For example, in the case of the sample application for cat door automation, change the line:

string trapDoorStatus = "Undetermined";to:

string trapDoorStatus = "";and run Stryker again. A mutant has survived:

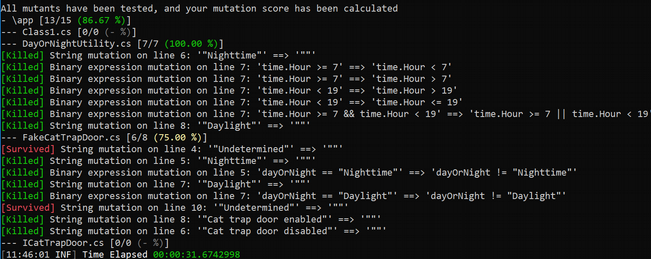

All mutants have been tested, and your mutation score has been calculated

- \app [13/14 (92.86%)]

[...]

[Survived] String mutation on line 4: '""' ==> '"Stryker was here!"'

[...]This time, you can see that Stryker mutated the line:

string trapDoorStatus = "";into:

string trapDoorStatus = ""Stryker was here!";This is a great example of how Stryker works: it mutates every line of our code, in a smart way, in order to see if there are further test cases we have yet to think about. It's forcing us to consider our expectations in greater depth.

Defeated by Stryker, you can attempt to improve the implemented code by adding more logic to it:

public string Control(string dayOrNight) {

string trapDoorStatus = "Undetermined";

if(dayOrNight == "Nighttime") {

trapDoorStatus = "Cat trap door disabled";

} else if(dayOrNight == "Daylight") {

trapDoorStatus = "Cat trap door enabled";

} else {

trapDoorStatus = "Undetermined";

}

return trapDoorStatus;

}But after running Stryker again, you see this attempt created a new mutant:

ll mutants have been tested, and your mutation score has been calculated

- \app [13/15 (86.67%)]

[...]

[Survived] String mutation on line 4: '"Undetermined"' ==> '""'

[...]

[Survived] String mutation on line 10: '"Undetermined"' ==> '""'

[...]

You cannot wiggle out of this tight spot by modifying the implemented code. It turns out the only way to kill surviving mutants is to describe additional expectations. And how do you describe expectations? By writing unit tests.

Unit testing for success

It's time to add a new unit test. Since the surviving mutant is located on line 4, you realize you have not specified expectations for the output with value "Undetermined."

Let's add a new unit test:

[Fact]

public void GivenIncorrectTimeOfDayReturnUndetermined() {

var expected = "Undetermined";

var actual = catTrapDoor.Control("Incorrect input");

Assert.Equal(expected, actual);

}The fix worked! Now all mutants are killed:

All mutants have been tested, and your mutation score has been calculated

- \app [14/14 (100%)]

[Killed] [...]You finally have a complete solution, including a description of what is expected as output if the system receives incorrect input values.

Mutation testing to the rescue

Suppose you decide to over-engineer a solution and add this method to the FakeCatTrapDoor:

private string getTrapDoorStatus(string dayOrNight) {

string status = "Everything okay";

if(dayOrNight != "Nighttime" || dayOrNight != "Daylight") {

status = "Undetermined";

}

return status;

}Then replace the line 4 statement:

string trapDoorStatus = "Undetermined";with:

string trapDoorStatus = getTrapDoorStatus(dayOrNight);When you run unit tests, everything passes:

Starting test execution, please wait...

Total tests: 5. Passed: 5. Failed: 0. Skipped: 0.

Test Run Successful.

Test execution time: 2.7191 SecondsThe test has passed without an issue. TDD has worked. But bring Stryker to the scene, and suddenly the picture looks a bit grim:

All mutants have been tested, and your mutation score has been calculated

- \app [14/20 (70%)]

[...]Stryker created 20 mutants; 14 mutants were killed, while six mutants survived. This lowers the success score to 70%. This means only 70% of our code is there to fulfill the described expectations. The other 30% of the code is there for no clear reason, which puts us at risk of misuse of that code.

In this case, Stryker helps fight the bloat. It discourages the use of unnecessary and convoluted logic because it is within the crevices of such unnecessary complex logic where bugs and defects breed.

Conclusion

As you've seen, mutation testing ensures that no uncertain fact goes unchecked.

You could compare Stryker to a chess master who is thinking of all possible moves to win a match. When Stryker is uncertain, it's telling you that winning is not yet a guarantee. The more unit tests we record as facts, the further we are in our match, and the more likely Stryker can predict a win. In any case, Stryker helps detect losing scenarios even when everything looks good on the surface.

It is always a good idea to engineer code properly. You've seen how TDD helps in that regard. TDD is especially useful when it comes to keeping your code extremely modular. However, TDD on its own is not enough for delivering lean code that works exactly to expectations. Developers can add code to an already implemented codebase without first describing the expectations. That puts the entire code base at risk. Mutation testing is especially useful in catching breaches in the regular test-driven development (TDD) cadence. You need to mutate every line of implemented code to be certain no line of code is there without a specific reason.

Now that you understand how mutation testing works, you should look into how to leverage it. Next time, I'll show you how to put mutation testing to good use when tackling more complex scenarios. I will also introduce more agile concepts to see how DevOps culture can benefit from maturing technology.

2 Comments