Interrupts are an essential part of how modern CPUs work. For example, every time you press a key on the keyboard, the CPU is interrupted so that the PC can read user input from the keyboard. This happens so quickly that you don't notice any change or impairment in user experience.

Moreover, the keyboard is not the only component that can cause interrupts. In general, there are three types of events that can cause the CPU to interrupt: Hardware interrupts, software interrupts, and exceptions. Before getting into the different types of interrupts, I'll define some terms.

Definitions

An interrupt request (IRQ) is requested by the programmable interrupt controller (PIC) with the aim of interrupting the CPU and executing the interrupt service routine (ISR). The ISR is a small program that processes certain data depending on the cause of the IRQ. Normal processing is interrupted until the ISR finishes.

In the past, IRQs were handled by a separate microchip—the PIC—and I/O devices were wired directly to the PIC. The PIC managed the various hardware IRQs and could talk directly to the CPU. When an IRQ occurred, the PIC wrote the data to the CPU and raised the interrupt request (INTR) pin.

Nowadays, IRQs are handled by an advanced programmable interrupt controller (APIC), which is part of the CPU. Each core has its own APIC.

Types of interrupts

As I mentioned, interrupts can be separated into three types depending on their source:

Hardware interrupts

When a hardware device wants to tell the CPU that certain data is ready to process (e.g., a keyboard entry or when a packet arrives at the network interface), it sends an IRQ to signal the CPU that the data is available. This invokes a specific ISR that was registered by the device driver during the kernel's start.

Software interrupts

When you're playing a video, it is essential to synchronize the music and video playback so that the music's speed doesn't vary. This is accomplished through a software interrupt that is repetitively fired by a precise timer system (known as jiffies). This timer enables your music player to synchronize. A software interrupt can also be invoked by a special instruction to read or write data to a hardware device.

Software interrupts are also crucial when real-time capability is required (such as in industrial applications). You can find more information about this in the Linux Foundation's article Intro to real-time Linux for embedded developers.

Exceptions

Exceptions are the type of interrupt that you probably know about. When the CPU executes a command that would result in division by zero or a page fault, any additional execution is interrupted. In such a case, you will be informed about it by a pop-up window or by seeing segmentation fault (core dumped) in the console output. But not every exception is caused by a faulty instruction.

Exceptions can be further divided into Faults, Traps, and Aborts.

- Faults: Faults are an exception that the system can correct, e.g., when a process tries to access data from a memory page that was swapped to the hard drive. The requested address is within the process address space, and the access rights are correct. If the page is not present in RAM, an IRQ is raised and it starts the page fault exception handler to load the desired memory page into RAM. If the operation is successful, execution will continue.

- Traps: Traps are mainly used for debugging. If you set a breakpoint in a program, you insert a special instruction that causes it to trigger a trap. A trap can trigger a context switch that allows your debugger to read and display values of local variables. Execution can continue afterward. Traps are also the default way to execute system calls (like killing a process).

- Aborts: Aborts are caused by hardware failure or inconsistent values in system tables. An abort does not report the location of the instruction that causes the exception. These are the most critical interrupts. An abort invokes the system's abort exception handler, which terminates the process that caused it.

Get hands-on

IRQs are ordered by priority in a vector on the APIC (0=highest priority). The first 32 interrupts (0–31) have a fixed sequence that is specified by the CPU. You can find an overview of them on OsDev's Exceptions page. Subsequent IRQs can be assigned differently. The interrupt descriptor table (IDT) contains the assignment between IRQ and ISR. Linux defines an IRQ vector from 0 to 256 for the assignment.

To print a list of registered interrupts on your system, open a console and type:

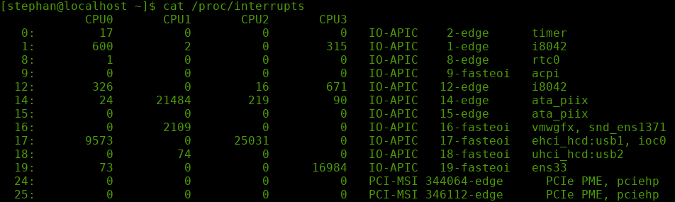

cat /proc/interruptsYou should see something like this:

Registered interrupts in kernel version 5.6.6. (Stephan Avenwedde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

From left to right, the columns are: IRQ vector, interrupt count per CPU (0 .. n), the hardware source, the hardware source's channel information, and the name of the device that caused the IRQ.

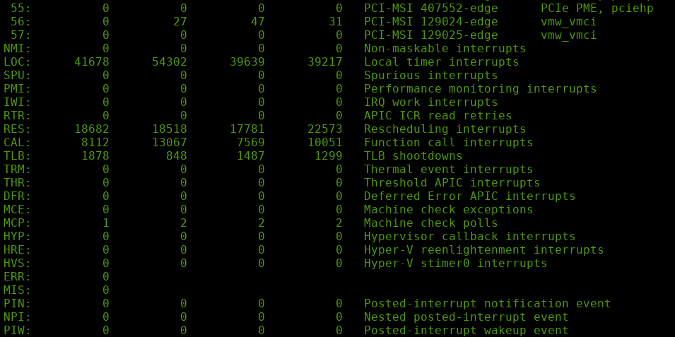

On the bottom of the table, there are some non-numeric interrupts. They are the architecture-specific interrupts, like the local timer interrupt (LOC) on IRQ 236. Some of them are specified in the Linux IRQ vector layout in the Linux kernel source tree.

Architecture-specific interrupts (Stephan Avenwedde, CC BY-SA 4.0)

To get a live view of this table, run:

watch -n1 "cat /proc/interrupts"Conclusion

Proper IRQ handling is essential for the proper interaction of hardware, drivers, and software. Luckily, the Linux kernel does a really good job, and a normal PC user will hardly notice anything about the kernel's entire interrupt handling.

This can get very complicated, and this article gives only a brief overview of the topic. Good sources of information for a deeper dive into the subject are the Linux Inside eBook (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) and the Linux Kernel Teaching repository.

1 Comment