The term "open source" was coined in 1998 at a strategy session held by Open Source Initiative (OSI). The OSI maintains the Open Source Definition (OSD), which places mandates on the distribution terms of any software that claims to be open source. The OSI also maintains a curated list of official open source licenses that meet these guidelines.

The OSD gives a clear definition of what open source software is, but doesn't provide much insight into how the adoption of open source affects a company's ability to build and deliver products or services that people want and need. Stated another way, there's still tremendous debate about the best ways to build a business based on open source.

In this first of a multi-part series, I will lay the groundwork for understanding what products are, what product managers do, and how open source can be considered a supply chain. In future articles, I will go deeper into each of these topics, but I'll start by dissecting some common, but fundamentally confusing vocabulary.

Development model or business model?

Open source adoption is common in products and solutions, but the verdict is out on what this truly means for product teams. Is open source a software development model or a business model? Even today, there are huge debates in open source circles.

People who think of open source as a development model emphasize collaboration, the decentralized nature in which code is written, and the licenses under which that code is released. Those who think of open source as a business model discuss monetization through support, services, software-as-a-service, paid features, and even in the context of inexpensive marketing or advertising. While there are surely valid arguments on both sides, neither of these models has ever satisfied everyone. Perhaps it's because we've never fully considered open source in the historical context of software products and their practical construction.

Instead of thinking about open source as a development model or a business model, perhaps companies should think in terms of a supply chain from which they can purchase technology.

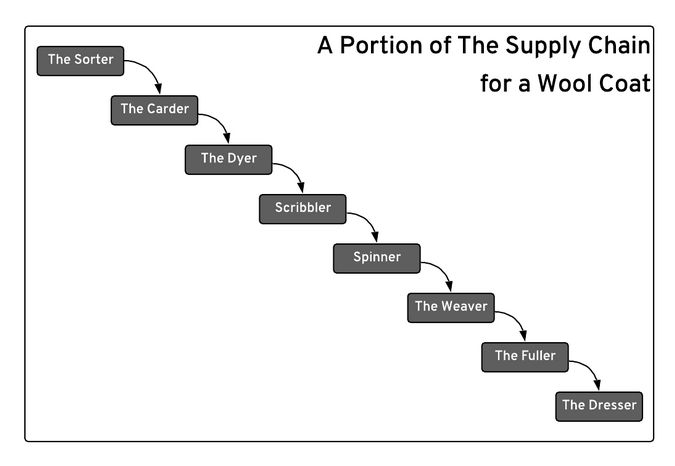

A supply chain includes the organizations, people, activities, information, and resources needed to create any product or service. This includes products as simple as a wool coat or as complex as an open source software project with thousands of dependencies. In The Wealth of Nations, the father of economics, Adam Smith, describes the supply chain for a wool coat:

"The shepherd, the sorter of the wool, the wool-comber or carder, the dyer, the scribbler, the spinner, the weaver, the fuller, the dresser, with many others, must all join their different arts in order to complete even this homely production."

(Scott McCarty, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Most of us probably haven't heard of the roles involved in the supply chain for a wool coat, but one thing is obvious: divisions of labor and collaboration are keys to a healthy supply chain, especially with open source.

Product or project?

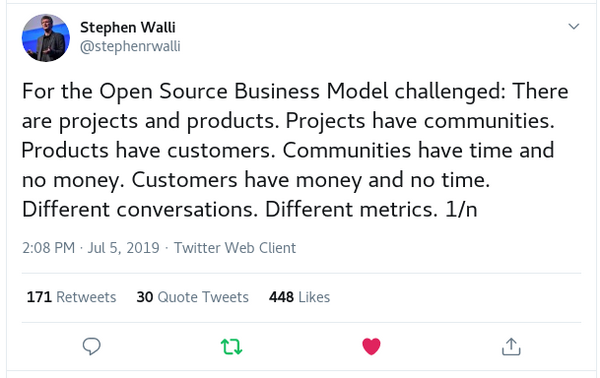

If you accept that open source is a supply chain for building solutions, this leads to another misunderstanding around projects and products. Paul Cormier, Red Hat's CEO, makes a pragmatic distinction between open source projects and open source products. While I agree with Paul, I am obliged to confess that most of the world doesn't recognize this crisp distinction. In 20 years of conversations with customers, partners, users, contributors, analysts, journalists, and even my own family, most people use the words project and product interchangeably.

I'll attempt to bring clarity by proposing a simple definition: Products are things that people buy with currency, while projects are things people participate in, contribute to, or use. That gets part of the way to a better definition, but to truly understand, you need to define what a product is in order to clearly see what a project isn't.

Software products, like any other products or services, have a whole host of activities required to bring them to market. They have business plans, pricing and packaging, positioning and messaging, distribution strategies, sales enablement, portfolio alignment, build/buy/partner decisions, and roadmaps. The teams managing these products conduct focus groups, analyze addressable markets, brief journalists and analysts about how their products fit into the marketplace, walk customers through roadmaps, and, most importantly, define those roadmaps based on the needs of paying customers. Product teams spend a lot of time and money understanding their customers' problems, but this is rarely the work output of community members.

Product teams have a fundamental choice about which suppliers they use in their products. This could mean using two, three, four, or even 10 different upstream projects in a product. It could also mean switching upstream projects when they no longer meet the needs of the customers buying the product. Finally, it could also mean positioning a partner's solution or different parts of the product portfolio to fill in gaps (i.e., address customer needs with solutions). The product team can also decide to use open source as one part of the supply chain and proprietary software as another part, thereby differentiating the product from the project. They can even make their product available only as a service; this is the power of pricing and packaging.

Nearly all products are built by adding a layer of differentiated value to a set of commodity components that are provided by suppliers. This is true, whether they're built on open source or proprietary components. Stated another way, upstream suppliers cannot provide the same solution as downstream products. When upstream projects and downstream products tackle the exact same business problem, there is low differentiation, which creates challenges. This is akin to upstream suppliers and the downstream product company both selling tires—the upstream supplier needs to sell tires, and the downstream product company needs to sell vehicles.

A lack of differentiation between the supply-chain components and the downstream product is where open source companies run into problems.

Everyday, product teams have to make pricing, packaging, build, buy, partner, and roadmap decisions driven by paying customers. This is what provides differentiation to a product and makes it fundamentally different from a community-driven, open source project.

Buying from the open source supply chain

Open source technology is free as in speech, not "free as in beer." Anyone can download and use open source software pretty much however they want, but as soon as you sell a product that uses open source, you have a responsibility to the customer. That responsibility includes things like verifying the software is always patched, secure, and runs well. A product team has a commitment to the customers and is responsible for every component chosen in the supply chain.

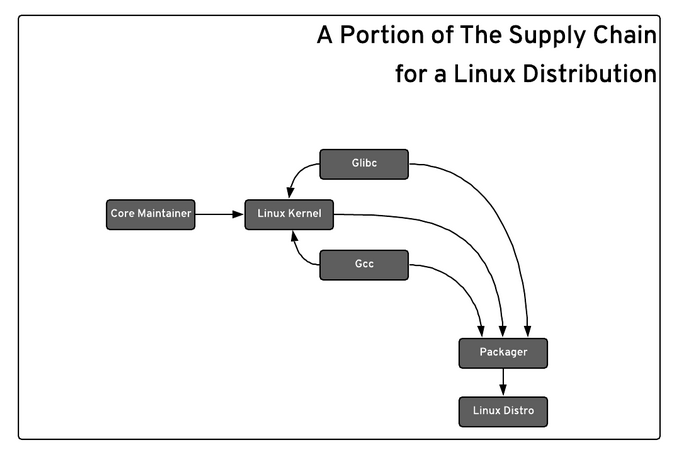

(Scott McCarty, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Stated another way, building a product on open source software is not free. It costs either time or money, and everyone knows time is money, so these are essentially the same thing. Therefore, it's genuinely correct to use the word "buy" to describe the relationship between product teams and the upstream open source projects that supply technology for those products.

From the perspective of the product team, each upstream project can be thought of as a supplier. The product team can "buy" from the open source suppliers by contributing the time and energy of engineers, documentation writers, testers, etc. Since time is money, every hour spent on upstream work can be measured in dollars.

This cost of consuming from the open source supply chain exists whether your organization is selling a product based on open source or building a solution for internal consumption. Building anything on open source comes with an implicit responsibility for the components selected and used. But, unlike a traditional supply chain, a dollar may not be a dollar (fill in your currency of choice).

Every dollar invested in an open source supply chain purchase might return $2, $3, or even $10 of value in return. The return on investment can be higher because other people and companies are also contributing value, as well as a diversity of ideas. Everyone who consumes from an open source supply chain inherits the total value. If the community is healthy, the value received is far above and beyond the contributions made.

There's another hidden benefit to purchasing from open source suppliers. Unlike traditional suppliers, community-driven, open source projects are not profit-driven entities with sales, marketing, and go-to-market costs. This is akin to buying from non-profit entities, but, once again, it's not "free as in beer." There's definitely a cost associated with purchasing from an open source supply chain and, in turn, providing a product to your customers.

A better metaphor for products

Perhaps no one has ever taken a product-centric view of open source because it grew up alongside the internet and the dot-com boom. This was a time of throwing money at ideas without having much of a business plan. Attempts to apply traditional business understanding post facto have led to debate over the definition of open source versus open core, as well as the roles and responsibilities of product teams. The software industry, and open source, in particular, has been notoriously confused about aligning product management and upstream engineering. The blurry line between project and product has even led to misunderstandings about what features upstream projects should focus on versus the downstream products.

Working as a member of the product team driving the roadmap for arguably the largest open source product in the world, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, I'd like to humbly propose a new paradigm within which to think about open source software:

Open source is a supply chain model.

It's not a huge intellectual leap, but this has profound implications on discussions, debates, and cognitive load when thinking about products that leverage open source.

Capturing value with open source

In recent years, arguments have been put forth asserting that there can only ever be one Red Hat; the narrative implies that only one company can grow into a multi-billion dollar business by selling support. This narrative is problematic because Red Hat doesn't make money from support, and it might even be argued that Red Hat Network was the first SaaS of open source. Second, other companies like SUSE, Cloudera, and Chef have captured quite a bit of value. Finally, many businesses start with a SaaS model and extend into adjacent on-premises businesses, like CloudBees.

All of these companies have been able to successfully use open source as a supply chain to create value while simultaneously capturing value by satisfying complex business problems that are not solved by the upstream project alone. Fundamentally, SaaS and hardware/software combinations are no different, although it might be argued that they are easier to monetize.

Fellow product managers, I urge you to start thinking about open source projects as a supply chain for your products. It will give you new clarity in making product-driven decisions and focusing on business needs instead of technology. With all supply chains, product managers have to treat their suppliers fairly. For example, downstream product teams can't tell upstream suppliers what to do. Downstream product teams also have to pay suppliers enough to keep them in business and continue to supply technology. These are just two examples of the clarity that comes from treating upstream, open source projects as suppliers, and it keeps the relationship much healthier.

(Scott McCarty, CC BY-SA 4.0)

There's a saying in music: It's not the notes you play, but the notes you don't play. Constraints breed creativity. If you know you can't differentiate your product based on the code from your upstream suppliers, your product team has to get creative. You have to identify other value worth purchasing. I'll dig into this later in the series; in the next article, I'll add clarity to the scope of what an open source product is and how to create value with it.

1 Comment