In this series of articles, I'm looking at the characteristics of different Python plotting libraries by making the same multi-bar plot in each one. This time I'm focusing on Bokeh (pronounced "BOE-kay").

Plotting in Bokeh is a little more complicated than in some of the other plotting libraries, but there's a payoff for the extra effort. Bokeh is designed both to allow you to create your own interactive plots on the web and to give you detailed control over how the interactivity works. I'll show this by adding a tooltip to the multi-bar plot I've been using in this series. It plots data from UK election results between 1966 and 2020.

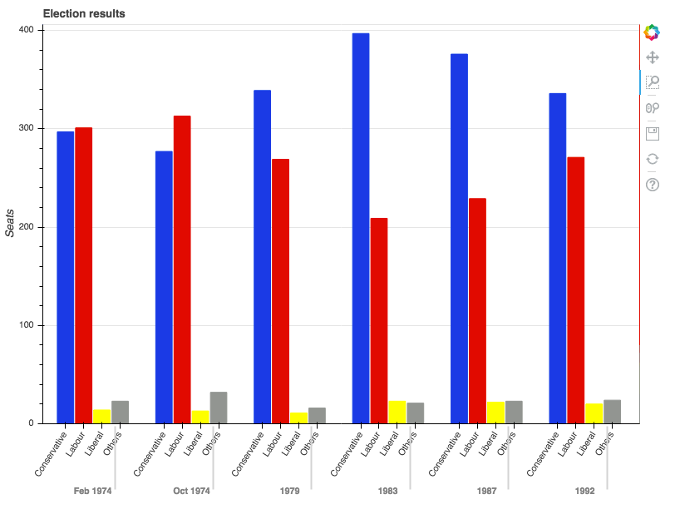

A zoomed-in view on the plot (© 2019 Anvil)

Making the multi-bar plot

Before we go further, note that you may need to tune your Python environment to get this code to run, including the following.

- Running a recent version of Python (instructions for Linux, Mac, and Windows)

- Verify you're running a version of Python that works with these libraries

The data is available online and can be imported using pandas:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv('https://anvil.works/blog/img/plotting-in-python/uk-election-results.csv')

Now we're ready to go.

To make the multi-bar plot, you need to massage your data a little.

The original data looks like this:

>> print(long)

year party seats

0 1966 Conservative 253

1 1970 Conservative 330

2 Feb 1974 Conservative 297

3 Oct 1974 Conservative 277

4 1979 Conservative 339

.. ... ... ...

103 2005 Others 30

104 2010 Others 29

105 2015 Others 80

106 2017 Others 59

107 2019 Others 72

[60 rows x 3 columns]You can think of the data as a series of seats values for each possible (year, party) combination. That's exactly how Bokeh thinks of it. You need to make a list of (year, party) tuples:

# Get a tuple for each possible (year, party) combination

x = [(str(r[1]['year']), r[1]['party']) for r in df.iterrows()]

# This comes out as [('1922', 'Conservative'), ('1923', 'Conservative'), ... ('2019', 'Others')]These will be the x-values. The y-values are simply the seats:

y = df['seats']Now you have data that looks something like this:

x y

('1966', 'Conservative') 253

('1970', 'Conservative') 330

('Feb 1974', 'Conservative') 297

('Oct 1974', 'Conservative') 277

('1979', 'Conservative') 339

... ... ...

('2005', 'Others') 30

('2010', 'Others') 29

('2015', 'Others') 80

('2017', 'Others') 59

('2019', 'Others') 72Bokeh needs you to wrap your data in some objects it provides, so it can give you the interactive functionality. Wrap your x and y data structures in a ColumnDataSource object:

from bokeh.models import ColumnDataSource

source = ColumnDataSource(data={'x': x, 'y': y})Then construct a Figure object and pass in your x-data wrapped in a FactorRange object:

from bokeh.plotting import figure

from bokeh.models import FactorRange

p = figure(x_range=FactorRange(*x), width=2000, title="Election results")You need to get Bokeh to create a colormap—this is a special DataSpec dictionary it produces from a color mapping you give it. In this case, the colormap is a simple mapping between the party name and a hex value:

from bokeh.transform import factor_cmap

cmap = {

'Conservative': '#0343df',

'Labour': '#e50000',

'Liberal': '#ffff14',

'Others': '#929591',

}

fill_color = factor_cmap('x', palette=list(cmap.values()), factors=list(cmap.keys()), start=1, end=2)Now you can create the bar chart:

p.vbar(x='x', top='y', width=0.9, source=source, fill_color=fill_color, line_color=fill_color)Visual representations of data on Bokeh charts are referred to as glyphs, so you've created a set of bar glyphs.

Tweak the details of the graph to get it looking how you want:

p.y_range.start = 0

p.x_range.range_padding = 0.1

p.yaxis.axis_label = 'Seats'

p.xaxis.major_label_orientation = 1

p.xgrid.grid_line_color = NoneAnd finally, tell Bokeh you'd like to see your plot now:

from bokeh.io import show

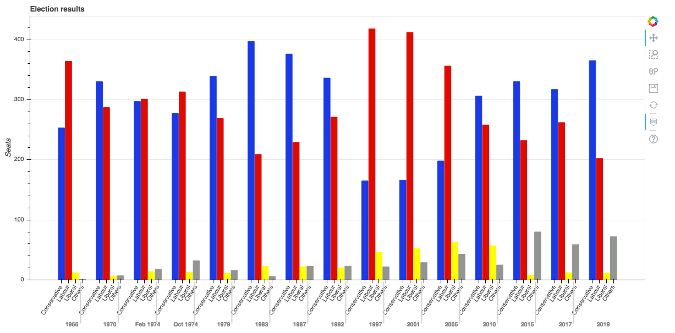

show(p)This writes the plot to an HTML file and opens it in the default web browser. Here's the result:

A multi-bar plot in Bokeh (© 2019 Anvil)

This already has some interactive features, such as a box zoom:

Bokeh's built-in box zoom (© 2019 Anvil)

But the great thing about Bokeh is how you can add your own interactivity. Explore that in the next section by adding tooltips to the bars.

Adding tooltips to the bars

To add tooltips to the bars, you just need to create a HoverTool object and add it to your figure:

h = HoverTool(tooltips=[

('Seats', '@y'),

('(Year, Party)', '(@x)')

])

p.add_tools(h)The arguments define what data is displayed on the tooltips. The variables @y and @x refer to the variables you passed into the ColumnDataSource. There are a few other values you could use; for example, the position of the cursor on the plot is given by $x and $y (no relation to @x and @y).

Here's the result:

The election graph, now with tooltips (© 2019 Anvil)

Thanks to Bokeh's HTML output, you get the full interactive experience when you embed the plot in a web app. You can copy this example as an Anvil app here (Note: Anvil requires registration to use).

Now you can see the reason for the extra effort of wrapping all your data in Bokeh in objects such as ColumnDataSource. In return, you can add interactivity with relative ease.

Back to simplicity: Altair

Bokeh is one of the four most popular plotting libraries, and this series is looking into what makes each of them special.

I'm also looking at a couple of libraries that stand out for their interesting approach. Next, I'll look at Altair, whose declarative API means it can make really complex plots without causing brain ache.

This article is based on How to make plots using Bokeh on Anvil's blog and is reused with permission.

2 Comments