There are plenty of great books to help you learn Python, but who actually reads these A to Z? (Spoiler: not me).

Many people find instructional books useful, but I do not typically learn by reading a book front to back. I learn by doing a project, struggling, figuring some things out, and then reading another book. So, throw away your book (for now), and let's learn some Python.

What follows is a guide to my first scraping project in Python. It is very low on assumed knowledge in Python and HTML. This is intended to illustrate how to access web page content with Python library requests and parse the content using BeatifulSoup4, as well as JSON and pandas. I will briefly introduce Selenium, but I will not delve deeply into how to use that library—that topic deserves its own tutorial. Ultimately I hope to show you some tricks and tips to make web scraping less overwhelming.

Installing our dependencies

All the resources from this guide are available at my GitHub repo. If you need help installing Python 3, check out the tutorials for Linux, Windows, and Mac.

$ python3 -m venv

$ source venv/bin/activate

$ pip install requests bs4 pandas

If you like using JupyterLab, you can run all the code using this notebook. There are a lot of ways to install JupyterLab, and this is one of them:

# from the same virtual environment as above, run:

$ pip install jupyterlabSetting a goal for our web scraping project

Now we have our dependencies installed, but what does it take to scrape a webpage?

Let's take a step back and be sure to clarify our goal. Here is my list of requirements for a successful web scraping project.

- We are gathering information that is worth the effort it takes to build a working web scraper.

- We are downloading information that can be legally and ethically gathered by a web scraper.

- We have some knowledge of how to find the target information in HTML code.

- We have the right tools: in this case, it's the libraries BeautifulSoup and requests.

- We know (or are willing to learn) how to parse JSON objects.

- We have enough data skills to use pandas.

A comment on HTML: While HTML is the beast that runs the Internet, what we mostly need to understand is how tags work. A tag is a collection of information sandwiched between angle-bracket enclosed labels. For example, here is a pretend tag, called "pro-tip":

<pro-tip> All you need to know about html is how tags work </pro-tip>

We can access the information in there ("All you need to know…") by calling its tag "pro-tip." How to find and access a tag will be addressed further in this tutorial. For more of a look at HTML basics, check out this article.

What to look for in a web scraping project

Some goals for gathering data are more suited for web scraping than others. My guidelines for what qualifies as a good project are as follows.

There is no public API available for the data. It would be much easier to capture structured data through an API, and it would help clarify both the legality and ethics of gathering the data. There needs to be a sizable amount of structured data with a regular, repeatable format to justify this effort. Web scraping can be a pain. BeautifulSoup (bs4) makes this easier, but there is no avoiding the individual idiosyncrasies of websites that will require customization. Identical formatting of the data is not required, but it does make things easier. The more "edge cases" (departures from the norm) present, the more complicated the scraping will be.

Disclaimer: I have zero legal training; the following is not intended to be formal legal advice.

On the note of legality, accessing vast troves of information can be intoxicating, but just because it's possible doesn't mean it should be done.

There is, thankfully, public information that can guide our morals and our web scrapers. Most websites have a robots.txt file associated with the site, indicating which scraping activities are permitted and which are not. It's largely there for interacting with search engines (the ultimate web scrapers). However, much of the information on websites is considered public information. As such, some consider the robots.txt file as a set of recommendations rather than a legally binding document. The robots.txt file does not address topics such as ethical gathering and usage of the data.

Questions I ask myself before beginning a scraping project:

- Am I scraping copyrighted material?

- Will my scraping activity compromise individual privacy?

- Am I making a large number of requests that may overload or damage a server?

- Is it possible the scraping will expose intellectual property I do not own?

- Are there terms of service governing use of the website, and am I following those?

- Will my scraping activities diminish the value of the original data? (for example, do I plan to repackage the data as-is and perhaps siphon off website traffic from the original source)?

When I scrape a site, I make sure I can answer "no" to all of those questions.

For a deeper look at the legal concerns, see the 2018 publications Legality and Ethics of Web Scraping by Krotov and Silva and Twenty Years of Web Scraping and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act by Sellars.

Now it's time to scrape!

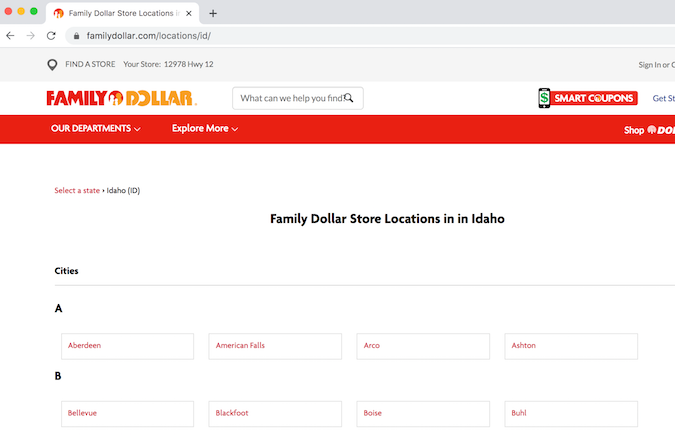

After assessing the above, I came up with a project. My goal was to extract addresses for all Family Dollar stores in Idaho. These stores have an outsized presence in rural areas, so I wanted to understand how many there are in a rather rural state.

The starting point is the location page for Family Dollar.

To begin, let's load up our prerequisites in our Python virtual environment. The code from here is meant to be added to a Python file (scraper.py if you're looking for a name) or be run in a cell in JupyterLab.

import requests # for making standard html requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup # magical tool for parsing html data

import json # for parsing data

from pandas import DataFrame as df # premier library for data organization

Next, we request data from our target URL.

page = requests.get("https://locations.familydollar.com/id/")

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.text, 'html.parser')

BeautifulSoup will take HTML or XML content and transform it into a complex tree of objects. Here are several common object types that we will use.

- BeautifulSoup—the parsed content

- Tag—a standard HTML tag, the main type of bs4 element you will encounter

- NavigableString—a string of text within a tag

- Comment—a special type of NavigableString

There is more to consider when we look at requests.get() output. I've only used page.text() to translate the requested page into something readable, but there are other output types:

- page.text() for text (most common)

- page.content() for byte-by-byte output

- page.json() for JSON objects

- page.raw() for the raw socket response (no thank you)

I have only worked on English-only sites using the Latin alphabet. The default encoding settings in requests have worked fine for that. However, there is a rich internet world beyond English-only sites. To ensure that requests correctly parses the content, you can set the encoding for the text:

page = requests.get(URL)

page.encoding = 'ISO-885901'

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.text, 'html.parser')

Taking a closer look at BeautifulSoup tags, we see:

- The bs4 element tag is capturing an HTML tag

- It has both a name and attributes that can be accessed like a dictionary: tag['someAttribute']

- If a tag has multiple attributes with the same name, only the first instance is accessed.

- A tag's children are accessed via tag.contents.

- All tag descendants can be accessed with tag.contents.

- You can always access the full contents as a string with: re.compile("your_string") instead of navigating the HTML tree.

Determine how to extract relevant content

Warning: this process can be frustrating.

Extraction during web scraping can be a daunting process filled with missteps. I think the best way to approach this is to start with one representative example and then scale up (this principle is true for any programming task). Viewing the page's HTML source code is essential. There are a number of ways to do this.

You can view the entire source code of a page using Python in your terminal (not recommended). Run this code at your own risk:

print(soup.prettify())

While printing out the entire source code for a page might work for a toy example shown in some tutorials, most modern websites have a massive amount of content on any one of their pages. Even the 404 page is likely to be filled with code for headers, footers, and so on.

It is usually easiest to browse the source code via View Page Source in your favorite browser (right-click, then select "view page source"). That is the most reliable way to find your target content (I will explain why in a moment).

In this instance, I need to find my target content—an address, city, state, and zip code—in this vast HTML ocean. Often, a simple search of the page source (ctrl + F) will yield the section where my target location is located. Once I can actually see an example of my target content (the address for at least one store), I look for an attribute or tag that sets this content apart from the rest.

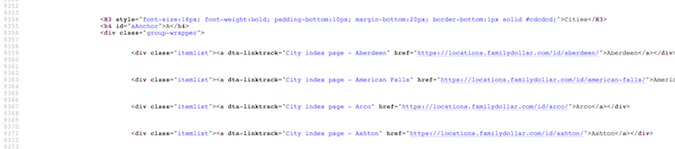

It would appear that first, I need to collect web addresses for different cities in Idaho with Family Dollar stores and visit those websites to get the address information. These web addresses all appear to be enclosed in a href tag. Great! I will try searching for that using the find_all command:

dollar_tree_list = soup.find_all('href')

dollar_tree_list

Searching for href did not yield anything, darn. This might have failed because href is nested inside the class itemlist. For the next attempt, search on item_list. Because "class" is a reserved word in Python, class_ is used instead. The bs4 function soup.find_all() turned out to be the Swiss army knife of bs4 functions.

dollar_tree_list = soup.find_all(class_ = 'itemlist')

for i in dollar_tree_list[:2]:

print(i)

Anecdotally, I found that searching for a specific class was often a successful approach. We can learn more about the object by finding out its type and length.

type(dollar_tree_list)

len(dollar_tree_list)

The content from this BeautifulSoup "ResultSet" can be extracted using .contents. This is also a good time to create a single representative example.

example = dollar_tree_list[2] # a representative example

example_content = example.contents

print(example_content)

Use .attr to find what attributes are present in the contents of this object. Note: .contents usually returns a list of exactly one item, so the first step is to index that item using the bracket notation.

example_content = example.contents[0]

example_content.attrs

Now that I can see that href is an attribute, that can be extracted like a dictionary item:

example_href = example_content['href']

print(example_href)

Putting together our web scraper

All that exploration has given us a path forward. Here's the cleaned-up version of the logic we figured out above.

city_hrefs = [] # initialise empty list

for i in dollar_tree_list:

cont = i.contents[0]

href = cont['href']

city_hrefs.append(href)

# check to be sure all went well

for i in city_hrefs[:2]:

print(i)

The output is a list of URLs of Family Dollar stores in Idaho to scrape.

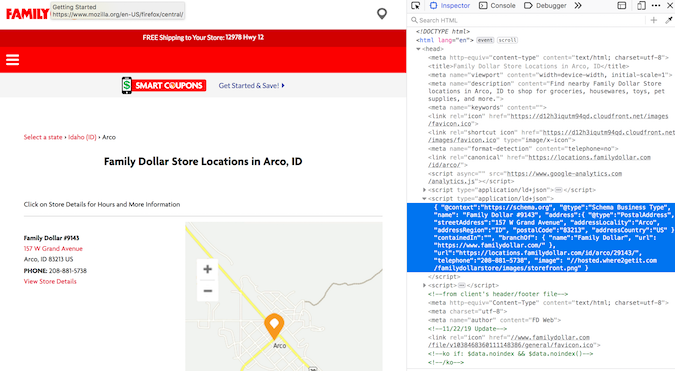

That said, I still don't have address information! Now, each city URL needs to be scraped to get this information. So we restart the process, using a single, representative example.

page2 = requests.get(city_hrefs[2]) # again establish a representative example

soup2 = BeautifulSoup(page2.text, 'html.parser')

The address information is nested within type= "application/ld+json". After doing a lot of geolocation scraping, I've come to recognize this as a common structure for storing address information. Fortunately, soup.find_all() also enables searching on type.

arco = soup2.find_all(type="application/ld+json")

print(arco[1])

The address information is in the second list member! Finally!

I extracted the contents (from the second list item) using .contents (this is a good default action after filtering the soup). Again, since the output of contents is a list of one, I indexed that list item:

arco_contents = arco[1].contents[0]

arco_contents

Wow, looking good. The format presented here is consistent with the JSON format (also, the type did have "json" in its name). A JSON object can act like a dictionary with nested dictionaries inside. It's actually a nice format to work with once you become familiar with it (and it's certainly much easier to program than a long series of RegEx commands). Although this structurally looks like a JSON object, it is still a bs4 object and needs a formal programmatic conversion to JSON to be accessed as a JSON object:

arco_json = json.loads(arco_contents)

type(arco_json)

print(arco_json)

In that content is a key called address that has the desired address information in the smaller nested dictionary. This can be retrieved thusly:

arco_address = arco_json['address']

arco_address

Okay, we're serious this time. Now I can iterate over the list store URLs in Idaho:

locs_dict = [] # initialise empty list

for link in city_hrefs:

locpage = requests.get(link) # request page info

locsoup = BeautifulSoup(locpage.text, 'html.parser')

# parse the page's content

locinfo = locsoup.find_all(type="application/ld+json")

# extract specific element

loccont = locinfo[1].contents[0]

# get contents from the bs4 element set

locjson = json.loads(loccont) # convert to json

locaddr = locjson['address'] # get address

locs_dict.append(locaddr) # add address to list

Cleaning our web scraping results with pandas

We have loads of data in a dictionary, but we have some additional crud that will make reusing our data more complex than it needs to be. To do some final data organization steps, we convert to a pandas data frame, drop the unneeded columns "@type" and "country"), and check the top five rows to ensure that everything looks alright.

locs_df = df.from_records(locs_dict)

locs_df.drop(['@type', 'addressCountry'], axis = 1, inplace = True)

locs_df.head(n = 5)

Make sure to save results!!

df.to_csv(locs_df, "family_dollar_ID_locations.csv", sep = ",", index = False)

We did it! There is a comma-separated list of all the Idaho Family Dollar stores. What a wild ride.

A few words on Selenium and data scraping

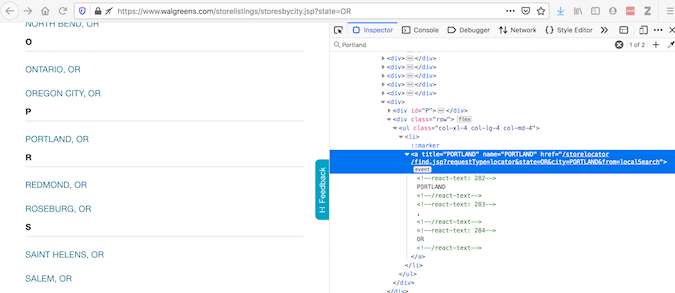

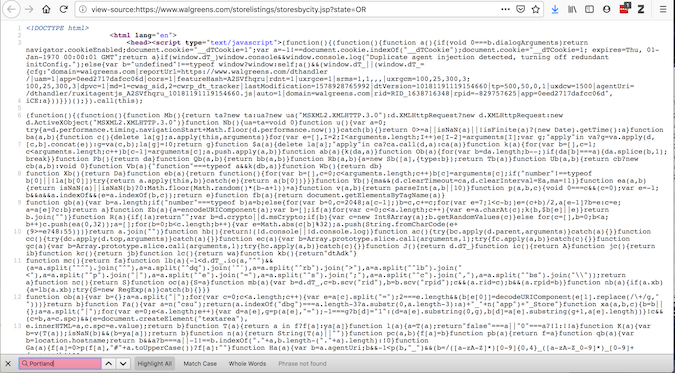

Selenium is a common utility for automatic interaction with a webpage. To explain why it's essential to use at times, let's go through an example using Walgreens' website. Inspect Element provides the code for what is displayed in a browser:

While View Page Source provides the code for what requests will obtain:

opensource.com

When these two don't agree, there are plugins modifying the source code—so, it should be accessed after the page has loaded in a browser. requests cannot do that, but Selenium can.

Selenium requires a web driver to retrieve the content. It actually opens a web browser, and this page content is collected. Selenium is powerful—it can interact with loaded content in many ways (read the documentation). After getting data with Selenium, continue to use BeautifulSoup as before:

url = "https://www.walgreens.com/storelistings/storesbycity.jsp?requestType=locator&state=ID"

driver = webdriver.Firefox(executable_path = 'mypath/geckodriver.exe')

driver.get(url)

soup_ID = BeautifulSoup(driver.page_source, 'html.parser')

store_link_soup = soup_ID.find_all(class_ = 'col-xl-4 col-lg-4 col-md-4')

I didn't need Selenium in the case of Family Dollar, but I do keep it on hand for those times when rendered content differs from source code.

Wrapping up

In conclusion, when using web scraping to accomplish a meaningful task:

- Be patient

- Consult the manuals (these are very helpful)

If you are curious about the answer:

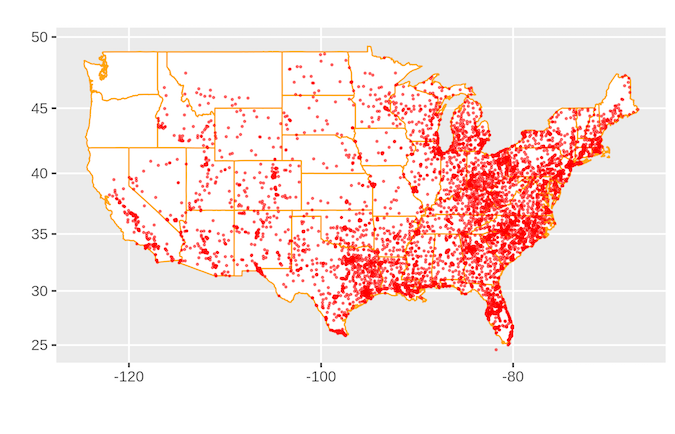

There are many many Family Dollar stores in America.

The complete source code is:

import requests

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import json

from pandas import DataFrame as df

page = requests.get("https://www.familydollar.com/locations/")

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.text, 'html.parser')

# find all state links

state_list = soup.find_all(class_ = 'itemlist')

state_links = []

for i in state_list:

cont = i.contents[0]

attr = cont.attrs

hrefs = attr['href']

state_links.append(hrefs)

# find all city links

city_links = []

for link in state_links:

page = requests.get(link)

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.text, 'html.parser')

familydollar_list = soup.find_all(class_ = 'itemlist')

for store in familydollar_list:

cont = store.contents[0]

attr = cont.attrs

city_hrefs = attr['href']

city_links.append(city_hrefs)

# to get individual store links

store_links = []

for link in city_links:

locpage = requests.get(link)

locsoup = BeautifulSoup(locpage.text, 'html.parser')

locinfo = locsoup.find_all(type="application/ld+json")

for i in locinfo:

loccont = i.contents[0]

locjson = json.loads(loccont)

try:

store_url = locjson['url']

store_links.append(store_url)

except:

pass

# get address and geolocation information

stores = []

for store in store_links:

storepage = requests.get(store)

storesoup = BeautifulSoup(storepage.text, 'html.parser')

storeinfo = storesoup.find_all(type="application/ld+json")

for i in storeinfo:

storecont = i.contents[0]

storejson = json.loads(storecont)

try:

store_addr = storejson['address']

store_addr.update(storejson['geo'])

stores.append(store_addr)

except:

pass

# final data parsing

stores_df = df.from_records(stores)

stores_df.drop(['@type', 'addressCountry'], axis = 1, inplace = True)

stores_df['Store'] = "Family Dollar"

df.to_csv(stores_df, "family_dollar_locations.csv", sep = ",", index = False)

--

Author's note: This article is an adaptation of a talk I gave at PyCascades in Portland, Oregon on February 9, 2020.

3 Comments