The plotting libraries available in Python offer multiple ways to present data according to your preferences, whether you prize flexibility, design, ease-of-use, or a particular style.

Plotting in Altair delivers a different solution than others which I find to be simpler as the amount of plotting done scales. It has an elegant interface, thanks to Vega, the declarative plotting language that allows you to define what your plots should look like, rather than writing loops and conditionals to construct them.

Fluent in plotting

I compare each Python plotting library by plotting the same multi-bar plot. Before we go further, note that you may need to tune your Python environment to get this code to run, including the following.

- Installing a recent version of Python (instructions for Linux, Mac, and Windows)

- Verify that version of Python works with the libraries used in the tutorial

The data is available online and can be imported using pandas:

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv('https://anvil.works/blog/img/plotting-in-python/uk-election-results.csv')

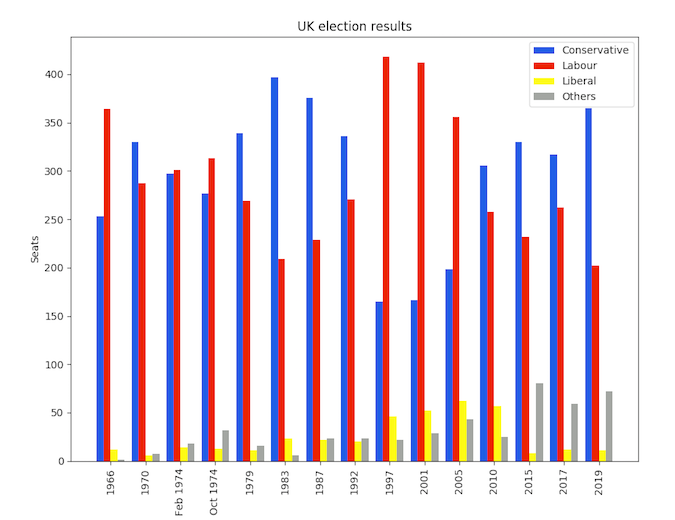

Now we're ready to go. As a point of comparison, this is the plot we made in Matplotlib:

Matplotlib plot of UK election results (© 2020 Anvil)

The Matplotlib plot took 16 lines of code to create, including manually calculating the positions of each bar.

Here's how to make a similar plot in Altair:

import altair as alt

chart = alt.Chart(df).mark_bar().encode(

x='party',

y='seats',

column='year',

color='party',

)

chart.save('altair-elections.html')Much more concise! Just like Seaborn, Altair works with data that has one column per variable (Long Form). This allows you to map each variable onto an aspect of the plot—Altair calls these aspects "channels." In our case, we want one bar per party on the x-axis, we want the seats each party won on the y-axis, and we want to group the bars into columns by year. We also want to color the bars by party. That's how you would describe it in words, and it's exactly what the code says!

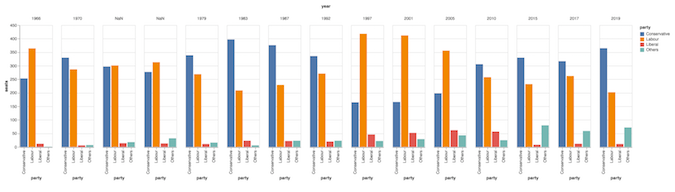

Here's what the plot looks like:

Altair plot with default styling (© 2020 Anvil)

Tweaking the style

That's not too far from what we want. The main difference from the Matplotlib plot is that each Altair year group is displayed with a little white space in between—this is just a feature of Altair's multi-bar plots, and it's not a problem.

However, there are a few other little style improvements that we do want to make.

Non-integer values

The two non-integer year names (Feb 1974 and Oct 1974) are displayed as NaN. We can fix these by casting our year values to strings:

df['year'] = df['year'].astype(str)Specifying sort order

We then also need to tell Altair how to sort the data. Altair allows us to specify more details about the column channel by passing it a Column object. So we tell it to sort in the order that the data appears in the DataFrame:

chart = alt.Chart(df).mark_bar().encode(

# ...

column=alt.Column('year', sort=list(df['year']), title=None),

# ...

)Removing axis titles

We have removed the "year" label from the top of the plot by setting title=None. Let's also remove the "party" labels from each column:

chart = alt.Chart(df).mark_bar().encode(

x=alt.X('party', title=None),

# ...

)Specifying a colormap

Finally, we want to specify our own colors to use for the bars. Altair lets us specify a mapping between values in a domain and colors in a range, which is exactly what we need:

cmap = {

'Conservative': '#0343df',

'Labour': '#e50000',

'Liberal': '#ffff14',

'Others': '#929591',

}

chart = alt.Chart(df).mark_bar().encode(

# ...

color=alt.Color('party', scale=alt.Scale(domain=list(cmap.keys()), range=list(cmap.values())))

)Final code with style tweaks

After applying these styling tweaks, our code is a little less pleasing to the eye, but it still uses the declarative approach that makes Altair so scalable. We're still assigning independent variables from our data to separate aspects of our plot, rather than performing complex data manipulations as we often need to do in Matplotlib. The only difference is that our variable names are now wrapped in objects such as alt.X() that let us tweak how they appear:

import altair as alt

from votes import long as df

cmap = {

'Conservative': '#0343df',

'Labour': '#e50000',

'Liberal': '#ffff14',

'Others': '#929591',

}

df['year'] = df['year'].astype(str)

# We're still assigning, e.g. 'party' to x, but now we've wrapped it

# in alt.X in order to specify its styling

chart = alt.Chart(df).mark_bar().encode(

x=alt.X('party', title=None),

y='seats',

column=alt.Column('year', sort=list(df['year']), title=None),

color=alt.Color('party', scale=alt.Scale(domain=list(cmap.keys()), range=list(cmap.values())))

)

chart.save('altair-elections.html')In fairness to Matplotlib, we've now reached the same number of lines of code (16) as we used there!

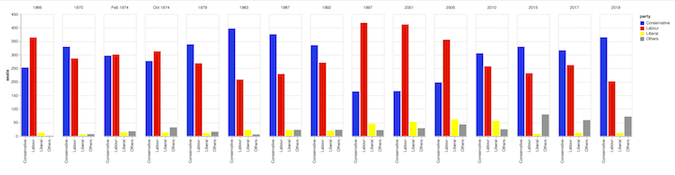

Here's the Altair plot with our styling tweaks applied:

The Altair plot with our custom styling (© 2020 Anvil)

Conclusion

While the amount of code it takes to plot using Altair is similar to other libraries, its declarative plotting language adds a layer of sophistication I have grown to appreciate. Altair also offers a cleanly separate way to tune and tweak the style, which keeps that syntax out of the code blocks meant for plotting. Altair is another great library when considering a plotting solution for Python. You can run this code interactively on Anvil (with an account) or locally using this open source runtime.

---

This article is based on Plotting in Altair on Anvil's blog and is reused with permission.

Comments are closed.