Of all the Linux commands out there (and there are many), the three most quintessential seem to be sed, awk, and grep. Maybe it's the arcane sound of their names, or the breadth of their potential use, or just their age, but when someone's giving an example of a "Linuxy" command, it's usually one of those three. And while sed and grep have several simple one-line standards, the less prestigious awk remains persistently prominent for being particularly puzzling.

You're likely to use sed for a quick string replacement or grep to filter for a pattern on a daily basis. You're far less likely to compose an awk command. I often wonder why this is, and I attribute it to a few things. First of all, many of us barely use sed and grep for anything but some variation upon these two commands:

$ sed -e 's/foo/bar/g' file.txt

$ grep foo file.txt

So, even though you might feel more comfortable with sed and grep, you may not use their full potential. Of course, there's no obligation to learn more about sed or grep, but I sometimes wonder about the way I "learn" commands. Instead of learning how a command works, I often learn a specific incantation that includes a command. As a result, I often feel a false familiarity with the command. I think I know a command because I can name three or four options off the top of my head, even though I don't know what the options do and can't quite put my finger on the syntax.

And that's the problem, I believe, that many people face when confronted with the power and flexibility of awk.

Learning awk to use awk

The basics of awk are surprisingly simple. It's often noted that awk is a programming language, and although it's a relatively basic one, it's true. This means you can learn awk the same way you learn a new coding language: learn its syntax using some basic commands, learn its vocabulary so you can build up to complex actions, and then practice, practice, practice.

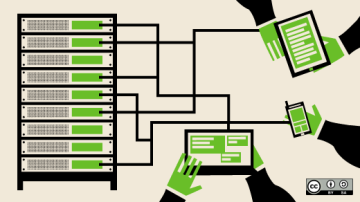

How awk parses input

Awk sees input, essentially, as an array. When awk scans over a text file, it treats each line, individually and in succession, as a record. Each record is broken into fields. Of course, awk must keep track of this information, and you can see that data using the NR (number of records) and NF (number of fields) built-in variables. For example, this gives you the line count of a file:

$ awk 'END { print NR;}' example.txt

36This also reveals something about awk syntax. Whether you're writing awk as a one-liner or as a self-contained script, the structure of an awk instruction is:

pattern or keyword { actions }In this example, the word END is a special, reserved keyword rather than a pattern. A similar keyword is BEGIN. With both of these keywords, awk just executes the action in braces at the start or end of parsing data.

You can use a pattern as a filter or qualifier so that awk only executes a given action when it is able to match your pattern to the current record. For instance, suppose you want to use awk, much as you would grep, to find the word Linux in a file of text:

$ awk '/Linux/ { print $0; }' os.txt

OS: CentOS Linux (10.1.1.8)

OS: CentOS Linux (10.1.1.9)

OS: Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) (10.1.1.11)

OS: Elementary Linux (10.1.2.4)

OS: Elementary Linux (10.1.2.5)

OS: Elementary Linux (10.1.2.6)For awk, each line in the file is a record, and each word in a record is a field. By default, fields are separated by a space. You can change that with the --field-separator option, which sets the FS (field separator) variable to whatever you want it to be:

$ awk --field-separator ':' '/Linux/ { print $2; }' os.txt

CentOS Linux (10.1.1.8)

CentOS Linux (10.1.1.9)

Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) (10.1.1.11)

Elementary Linux (10.1.2.4)

Elementary Linux (10.1.2.5)

Elementary Linux (10.1.2.6)In this sample, there's an empty space before each listing because there's a blank space after each colon (:) in the source text. This isn't cut, though, so the field separator needn't be limited to one character:

$ awk --field-separator ': ' '/Linux/ { print $2; }' os.txt

CentOS Linux (10.1.1.8)

CentOS Linux (10.1.1.9)

Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) (10.1.1.11)

Elementary Linux (10.1.2.4)

Elementary Linux (10.1.2.5)

Elementary Linux (10.1.2.6)Functions in awk

You can build your own functions in awk using this syntax:

name(parameters) { actions }Functions are important because they allow you to write code once and reuse it throughout your work. When constructing one-liners, custom functions are a little less useful than they are in scripts, but awk defines many functions for you already. They work basically the same as any function in any other language or spreadsheet: You learn the order that the function needs information from you, and you can feed it whatever you want to get the results.

There are functions to perform mathematical operations and string processing. The math ones are often fairly straightforward. You provide a number, and it crunches it:

$ awk 'BEGIN { print sqrt(1764); }'

42String functions can be more complex but are well documented in the GNU awk manual. For example, the split function takes an entity that awk views as a single field and splits it into different parts. It requires a field, a variable to use as an array containing each part of the split, and the character you want to use as the delimiter.

Using the output of the previous examples, I know that there's an IP address at the very end of each record. In this case, I can send just the last field of a record to the split function by referencing the variable NF because it contains the number of fields (and the final field must be the highest number):

$ awk --field-separator ': ' '/Linux/ { split($NF, IP, "."); print "subnet: " IP[3]; }' os.txt

subnet: 1

subnet: 1

subnet: 1

subnet: 2

subnet: 2

subnet: 2There are many more functions, and there's no reason to limit yourself to one per block of awk code. You can construct complex pipelines with awk in your terminal, or you can write awk scripts to define and utilize your own functions.

Download the eBook

Learning awk is mostly a matter of using awk. Use it even if it means duplicating functionality you already have with sed or grep or cut or tr or any other perfectly valid commands. Once you get comfortable with it, you can write Bash functions that invoke your custom awk commands for easier use. And eventually, you'll be able to write scripts to parse complex datasets.

Download our eBook to learn everything you need to know about awk, and start using it today.

1 Comment