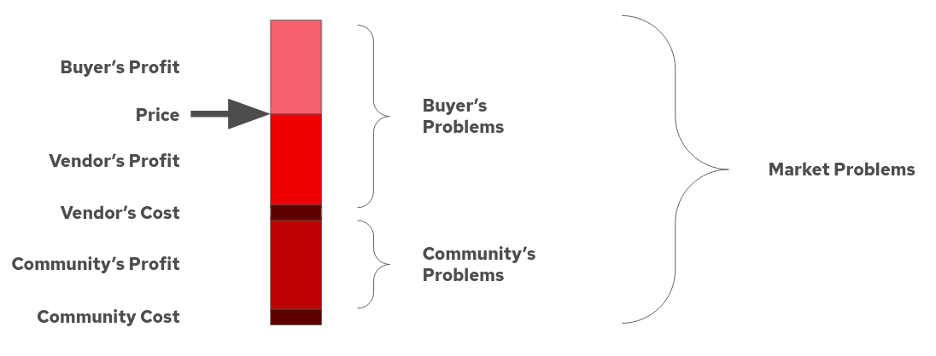

What is open core? Is a project open core, or is a business open core? That's debatable. Like open source, some view it as a development model, others view it as a business model. As a product manager, I view it more in the context of value creation and value capture.

(Scott McCarty, CC BY-SA 4.0)

With open source, an engineering team can capture more value than it contributes. An engineer participating in an open source project can contribute $1 worth of code, yet get back $10, $20, $30, or more worth of value. This value is measured in both personal brand, as well as ability to lead and influence the project in a direction that is beneficial to their employer.

With open core, at least some of the code is proprietary. With proprietary code, a company hires engineers, solves business problems, and charges for that software. For the proprietary portion of the code base, there is no community-based engineering, so there's no process by which a community member can profit by participating. With proprietary code, a dollar invested in engineering is a dollar returned in code. Unlike open source, a proprietary development process can't return more value than the engineering team contributes (see also: Why Red Hat is investing in CRI-O and Podman).

This lack of community profit is really important when analyzing open core. There is no community for that part of the code, so there is no community participation, no community profit. If there is no community, there is no potential for a community member to gain the standard benefits of open source (personal brand, influence, right to use, learning, etc.).

There's no differential value created with open core, so in 18 ways to differentiate open source products from upstream suppliers, I describe it as a methodology for capturing value. Community-driven open source is about value creation, not value capture. This is a fundamental tension between open source and open core.

Open core versus glue code

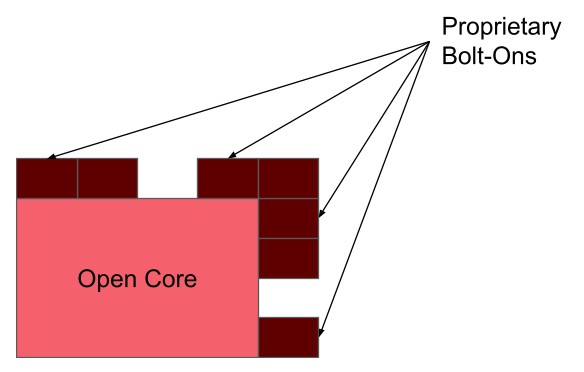

First, let's take a look at what people typically view as open source. As described on Wikipedia, "the open-core model primarily involves offering a 'core' or feature-limited version of a software product as free and open-source software, while offering 'commercial' versions or add-ons as proprietary software." The drawing below shows this model graphically.

An example of this model is SugarCRM, which had a core, open source piece of software as well as a bunch of plugins, many of which were proprietary. Another example of this is the original plan Microsoft had for the Hot Reload feature in .Net (which has since then been reversed).

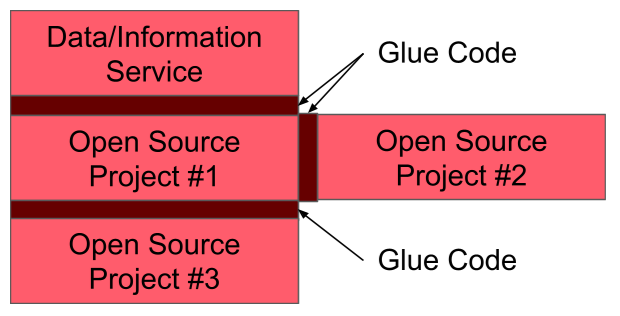

Another related model is what I'll refer to as glue code. Glue code doesn't directly provide a customer business value. Instead, it hangs a bunch of projects together. Notice, in this example, I demonstrate three open source projects, one data-driven API service, and some glue code that holds it all together. Glue code can be open source or proprietary, but this is not what people typically think of when they talk about open core.

An example of open source glue code is Red Hat Satellite Server. It's made up of multiple upstream open source projects like Foreman, Candlepin, Pulp, and Katello, as well as a connection to a data service for updates (as well as connections with tools like Red Hat Insights). In the case of Satellite server, all of the glue code is open source, but one can easily imagine how other companies might make the choice to employ proprietary code for this functionality.

When open core conflicts with community goals

The classic problem with open core is when the upstream community wants to implement a feature that is in one of the proprietary bolt-ons. The company or product which employs the open core model has an incentive to stop this from happening in the open source project on which the proprietary code relies. This creates some serious issues for both the upstream community and for customers.

Potential customers will be incentivized to participate in the community to implement the proprietary features which are perceived as missing. Community members who try to implement these features will be shocked or annoyed when their pull requests are difficult to get accepted or rejected outright.

I've never seen a serious solution for this problem. In this video, How To Do Open Core Well: 6 Concrete Recommendations, Jono Bacon recommends being upfront with community members. He recommends telling them that pull requests which compete with proprietary product features will be rejected. While that's better than not being upfront, it's not a scalable solution. Both the upstream project and the downstream product with proprietary features are constantly changing landscapes. Often, community contributors aren't even paying attention to the downstream product and have no idea which features are implemented downstream, or worse, on the roadmap to be implemented as proprietary features. The upstream community is rarely emotionally engaged with the business problems solved by downstream products, and can easily be confused when their pull requests are rejected.

Even if the community is willing to accept the no-go zones (example: GitLab Features by Paid Tier), this makes it a high probability that the open source project will be a single-vendor endeavor (example: GitLab contributions are primarily GitLab employees). It's highly unlikely that competitors will participate, and this will intrinsically limit the value creation of the community. The open core business could still capture value through thought leadership, technology adoption, and customer loyalty, but arguably they will never truly create more code value than they invest.

Apart from these problems, if an upstream project truly adheres to open governance, there's actually nothing the open core business can do to prevent proprietary features from being implemented. Intra-project (within a single project) proprietary code just doesn't work.

When open core might work

Glue code is a place where open core or proprietary code might work. I'm not advocating for open core, and I often think it's inefficient, but I want to be honest with my analysis. There are indeed natural boundaries between open source projects. Going back to my open source as a supply chain thesis (see also: The Delicate Art of Product Management with Open Source), a fuel injector is a fuel injector; it's not an alternator. These natural demarcation points do make good areas for differentiation of the downstream product from the upstream project (see also: 18 Ways to differentiate open source software products from their upstream projects).

A classic example of proprietary glue code is the original Red Hat Network (RHN), released in the year 2000. RHN was essentially a SaaS offering which provided updates for Red Hat Linux machines, and this was before Red Hat Enterprise Linux was even a thing. For context, when RHN was released, the term open core wasn't even invented yet (coined in 2008), coincidentally the same year that the upstream Spacewalk project was released. Back then, everyone was still learning the core competencies of how to do open source well.

In retrospect, I don't think it's a coincidence that RHN existed at the nexus of the natural demarcation point between an upstream Linux distribution and pay-for offering. This naturally fits the mental model of differentiating a product from the upstream supplier. It might be tempting to conclude - "See!?!? The largest open source company in the world differentiated itself with proprietary code! Open core is the reason Red Hat survived and flourished" - but I'd be careful not to confuse correlation with causation. Red Hat eventually open sourced RHN as Spacewalk and never took a hit to revenue.

Pivoting slightly, one could also make an argument that the cloud providers often follow this model today. It's well known in the industry that most of the large cloud providers carry their own forks of the Linux kernel. These forks have proprietary extensions which make Linux usable in their environments. These features don't solve a customer's business problem directly but instead solve the cloud provider's problems. They're essentially glue code.

Cloud providers have a slightly different motivation for not getting these changes upstream. For them, carrying a fork is often cheaper and/or easier (though not easy) than contributing these features upstream, especially when the changes are often not wanted by the Linux kernel community. Cloud providers are often choosing the best bad idea out of a bunch of bad ideas.

Open core glue code might be called inter-project (between multiple projects) proprietary code. This might work, but arguably, this kind of code is already difficult to implement and doesn't need the perceived "protections" of a proprietary license. Stated another way, open source contributors aren't necessarily incentivized to work on and maintain glue code. It's a natural place where a vendor can differentiate. Often glue code is complex and requires specific integrations between specific versions of upstream projects for specific life cycle requirements. All of these specific requirements make glue code a great place for a product to differentiate itself from the upstream projects without the need for a proprietary license. The velocity (speed and direction) of enterprise integrations are quite different from the velocity needed for collaboration between multiple upstream projects. This velocity mismatch between upstream community needs, and downstream customer needs is a perfect place for differentiation without the need for open core.

Conclusion

Can open core work? Is it better than open source? Should everyone use it? It seems obvious that Open core can work, but only in very specific situations with very specific types of software (ex. glue code). It seems less obvious that there's any argument that open core is actually better for creating value. Therefore, I do not recommend open core for most businesses. Furthermore, I think the percieved protections that it offers are actually unnecessary.

Often, vendors find natural places to compete with each other. For example, SUSE runs the OpenSUSE Build Service, which is based on completely open source code. Even though Red Hat could download the source code and set up a competing build service, they haven't. In fact, the upstream Podman project, which is heavily sponsored by Red Hat, uses the OpenSUSE build service. Though SUSE could easily make this code proprietary, they don't need to. Setting up, running, and maintaining a competing service is a lot of work and doesn't necessarily provide Red Hat customers with a lot of value.

I still think Open Core is a step in the right direction from fully proprietary code (example: GitLab is open core, GitHub is closed source), but I don't see a compelling reason to promote it as a better alternative to completely open source. In fact, I think it's exceedingly difficult to do open core well and likely impossible to genuinely create differentiated value with it (see also: The community-led renaissance of open source and Fauxpen source is bad for business).

This thesis on open core was developed by working with and learning from hundreds of passionate people in Open Source, including engineers, product managers, marketing managers, sales people, and some of the foremost lawyers in this space. To release new features and capabilities in Red Hat Enterprise Linux and OpenShift, like launching Red Hat Universal Base Image, I've worked closely with so many different teams at Red Hat. I've absorbed 25+ years of institutional knowledge, in my 10+ years here. Now, I'm trying to formalize this a bit in public work like The Delicate Art of Product Management with Open Source and follow-on articles like this one.

This work has contributed to my recent promotion to Senior Principal Product Manager of RHEL for Server, arguably the largest open source business in the world. Even with this experience, I'm constantly listening, learning, and seeking truth. I'd love to discuss this subject further in the comments or on Twitter (@fatherlinux).

7 Comments