Many people consider hard drives secure because they physically own them. It's difficult to read the data on a hard drive that you don't have, and many people think that protecting their computer with a passphrase makes the data on the drive unreadable.

This isn't always the case, partly because, in some cases, a passphrase serves only to unlock a user session. In other words, you can power on a computer, but because you don't have its passphrase, you can't get to the desktop, and so you have no way to open files to look at them.

The problem, as many a computer technician understands, is that hard drives can be extracted from computers, and some drives are already external by design (USB thumb drives, for instance), so they can be attached to any computer for full access to the data on them. You don't have to physically separate a drive from its computer host for this trick to work, either. Computers can be booted from a portable boot drive, which separates a drive from its host operating system and turns it into, virtually, an external drive available for reading.

The answer is to place the data on a drive into a digital vault that can't be opened without information that only you have access to.

Linux Unified Key Setup (LUKS) is a disk-encryption system. It provides a generic key store (and associated metadata and recovery aids) in a dedicated area on a disk with the ability to use multiple passphrases (or key files) to unlock a stored key. It's designed to be flexible and can even store metadata externally so that it can be integrated with other tools. The result is full-drive encryption, so you can store all of your data confident that it's safe—even if your drive is separated, either physically or through software, from your computer.

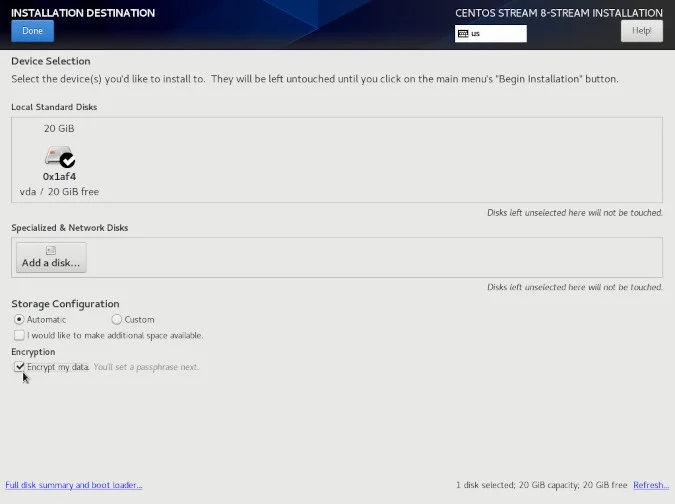

Encrypting during installation

The easiest way to implement full-drive encryption is to select the option during installation. Most modern Linux distributions offer this as an option, so it's usually a trivial process.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

This establishes everything you need: an encrypted drive requiring a passphrase before your system can boot. If the drive is extracted from your computer or accessed from another operating system running on your computer, the drive must be decrypted by LUKS before it can be mounted.

Encrypting external drives

It's not common to separate an internal hard drive from its computer, but external drives are designed to travel. As technology gets smaller and smaller, it's easier to put a portable drive on your keychain and carry it around with you every day. The obvious danger, however, is that these are also pretty easy to misplace. I've found abandoned drives in the USB ports of hotel lobby computers, business center printers, classrooms, and even a laundromat. Most of these didn't include personal information, but it's an easy mistake to make.

You can mitigate against misplacing important data by encrypting your external drives.

LUKS and its frontend cryptsetup provide a way to do this on Linux. As Linux does during installation, you can encrypt the entire drive so that it requires a passphrase to mount it.

How to encrypt an external drive with LUKS

First, you need an empty external drive (or a drive with contents you're willing to erase). This process overwrites all the data on a drive, so if you have data that you want to keep on the drive, back it up first.

1. Find your drive

I used a small USB thumb drive. To protect you from accidentally erasing data, the drive referenced in this article is located at the imaginary location /dev/sdX. Attach your drive and find its location:

$ lsblk

sda 8:0 0 111.8G 0 disk

sda1 8:1 0 111.8G 0 part /

sdb 8:112 1 57.6G 0 disk

sdb1 8:113 1 57.6G 0 part /mydrive

sdX 8:128 1 1.8G 0 disk

sdX1 8:129 1 1.8G 0 partI know that my demo drive is located at /dev/sdX because I recognize its size (1.8GB), and it's also the last drive I attached (with sda being the first, sdb the second, sdc the third, and so on). The /dev/sdX1 designator means the drive has 1 partition.

If you're unsure, remove your drive, look at the output of lsblk, and then attach your drive and look at lsblk again.

Make sure you identify the correct drive because encrypting it overwrites everything on it. My drive is not empty, but it contains copies of documents I have copies of elsewhere, so losing this data isn't significant to me.

2. Clear the drive

To proceed, destroy the drive's partition table by overwriting the drive's head with zeros:

$ sudo dd if=/dev/zero of=/dev/sdX count=4096This step isn't strictly necessary, but I like to start with a clean slate.

3. Format your drive for LUKS

The cryptsetup command is a frontend for managing LUKS volumes. The luksFormat subcommand creates a sort of LUKS vault that's password-protected and can house a secured filesystem.

When you create a LUKS partition, you're warned about overwriting data and then prompted to create a passphrase for your drive:

$ sudo cryptsetup luksFormat /dev/sdX

WARNING!

========

This will overwrite data on /dev/sdX irrevocably.

Are you sure? (Type uppercase yes): YES

Enter passphrase:

Verify passphrase:4. Open the LUKS volume

Now you have a fully encrypted vault on your drive. Prying eyes, including your own right now, are kept out of this LUKS partition. So to use it, you must open it with your passphrase. Open the LUKS vault with cryptsetup open along with the device location (/dev/sdX, in my example) and an arbitrary name for your opened vault:

$ cryptsetup open /dev/sdX vaultdriveI use vaultdrive in this example, but you can name your vault anything you want, and you can give it a different name every time you open it.

LUKS volumes are opened in a special device location called /dev/mapper. You can list the files there to check that your vault was added:

$ ls /dev/mapper

control vaultdriveYou can close a LUKS volume at any time using the close subcommand:

$ cryptsetup close vaultdriveThis removes the volume from /dev/mapper.

5. Create a filesystem

Now that you have your LUKS volume decrypted and open, you must create a filesystem there to store data in it. In my example, I use XFS, but you can use ext4 or JFS or any filesystem you want:

$ sudo mkfs.xfs -f -L myvault /dev/mapper/vaultdriveMount and unmount a LUKS volume

You can mount a LUKS volume from a terminal with the mount command. Assume you have a directory called /mnt/hd and want to mount your LUKS volume there:

$ sudo cryptsetup open /dev/sdX vaultdrive

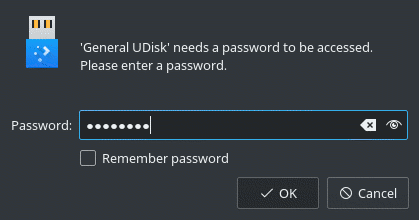

$ sudo mount /dev/mapper/vaultdrive /mnt/hdLUKS also integrates into popular Linux desktops. For instance, when I attach an encrypted drive to my workstation running KDE or my laptop running GNOME, my file manager prompts me for a passphrase before it mounts the drive.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Encryption is protection

Linux makes encryption easier than ever. It's so easy, in fact, that it's nearly unnoticeable. The next time you format an external drive for Linux, consider using LUKS first. It integrates seamlessly with your Linux desktop and protects your important data from accidental exposure.

Comments are closed.