In the early days, computers were big and expensive. There were few users in the world, and they had to reserve time on a computer (and show up in person) to have their punchcards processed. Systems called mainframes made many innovations and enabled time-shared tasks on terminals (like desktop computers, but without their own CPU).

Skip forward to today, when powerful computation is as cheap as US$35 and no larger than a credit card. That doesn't even begin to cover all the little devices in modern life that gather and process data. Take a high-level view of this collection of computers, and you can imagine all of these devices outnumbering grains of sands or particles in a cloud.

It so happens that the term "cloud computing" is already occupied, so there needs to be a unique name for the network comprised of the Internet of Things (IoT) and other strategically situated servers. And besides, if there's already a cloud representing nodes of a data center, then there's surely something unique about the nodes intermingling with us folk outside that cloud.

Welcome to fog computing

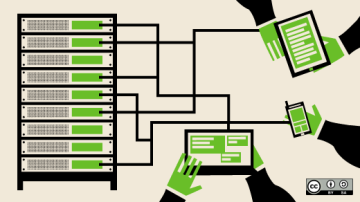

The cloud delivers computing services over the internet. But the data centers that make up the cloud are big and relatively few compared to their number of potential clients. This suggests potential bottlenecks when data is sent back and forth between the cloud and its many users.

Fog computing, by contrast, can outnumber its potential clients without risking a bottleneck because the devices perform much of the data collection or computation. It's the outer "edge" of the cloud, the part of a cloud that touches down to the ground.

Fog and edge computing

Fog computing and edge computing are essentially synonymous. Both have strong associations with both the cloud and IoT and make the same architectural assumptions:

- The closer you are to the CPU doing the work, the faster the data transfer.

- Like Linux, there's a strong advantage to having small, purpose-built computers that can "do one thing and do it well." (Of course, our devices actually do more than just one thing, but from a high-level view, a smartwatch you bought to monitor your health is essentially doing "one" thing.)

- Going offline is inevitable, but a good device can function just as effectively in the interim and then sync up when reconnected.

- Local devices can be simpler and cheaper than large data centers.

Networking on the edge

It's tempting to view fog computing as a completely separate entity from the cloud, but they're just two parts of the whole. The cloud needs the infrastructure of the digital enterprise, including public cloud providers, telecommunication companies, and even specialized corporations running their own services. Localized services are also important to provide waystations between the cloud core and its millions and millions of clients.

[Read next: An Architect's guide to edge computing essentials]

Fog computing, located at the edge of the cloud, intermingles with clients wherever they are located. Sometimes, this is a consumer setting, such as your own home or car, while other times, it's a business interest, such as price-monitoring devices in a retail store or vital safety sensors on a factory floor.

Fog computing is all around you

Fog computing is built up of all the connected devices in our lives: drones, phones, watches, fitness monitors, security monitors, home automation, portable gaming devices, gardening automation, weather sensors, air-quality monitors, and much, much more. Ideally, the data it provides helps to build a better and more informed future. There are lots of great open source projects out there that are working toward improving health and wellness—or even just making life a little more entertaining—and it's all happening thanks to fog and cloud computing. Our job, however, is to make sure it stays open.

Comments are closed.