Google v. Oracle has finally concluded in a sweeping 6-2 decision by the US Supreme Court favoring Google and adding further clarity on the freedom to use application programming interfaces (APIs). Software developers can benefit from this decision.

The open source community has closely followed the litigation between Google and Oracle due to its potential impact on the reuse of APIs. It has been assumed for many decades that APIs are not protected by copyright and are free to use by anyone to both create new and improved software modules and to integrate with existing modules that use such interfaces.

This case involves Google's use of a certain portion of the API from Oracle's Java SE when Google created Android. This case went through over 10 years of protracted litigation in the lower courts. The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) had previously held that 1) Oracle's copyright in a portion of the Java SE API copied by Google was copyrightable, and 2) Google's use was not excused as fair use under the law. This meant that Google would have been liable for copyright infringement for that portion of Oracle's Java SE API used in Android. If this holding were left to stand, it would not only have been a loss for Google but also for the software development community, including open source.

Unrestricted use of APIs has been the norm for decades and a key driver of innovation, including the modern internet and countless software modules and devices that communicate with each other using such interfaces. The fact is, the software industry was rarely concerned about the use of APIs until Oracle decided to make a federal case about it.

It is unfortunate that the software industry was put through this turmoil for over a decade. However, the Supreme Court's decision provides a new explanation and framework for analyzing use of software interfaces, and it is largely good news. In short, while the court did not overturn the copyrightability ruling, which would have been the best news from the perspective of software developers, it ruled strongly in favor of Google on whether Google's use was a fair use as a matter of law.

What is an API? It depends who you ask

Before I begin a more detailed description of this case and what the result means for software developers, I need to define an API. This is a significant source of confusion and made worse by the court adopting a definition that does not reflect the conventional meaning.

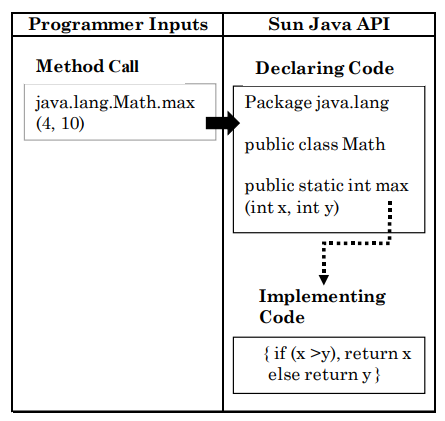

The Supreme Court uses the following diagram to describe what it refers to as an API:

(Source: Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., No. 18-956, US Apr. 5, 2021; pg. 38)

In the court's definition, an API includes both "declaring code" and "implementing code"—terms adopted by the court, although they are not used by developers in Java or other programming languages. The declaring code (what Java developers call the method declaration) declares the name of the method and its inputs and outputs. In the example above, the declaring code declares the method name, "max," and further declares that it receives two integers, "x" and "y," and returns an integer of the result.

Implementing code (what Java developers call the method body) consists of instructions that implement the functions of the method. So in the example above, the implementing code would use computer instructions and logic to determine whether x or y is the larger number and return the larger number.

At issue in this case was the declaring code only. Google was accused of copying portions of the declaring code of Java SE for use in Android and the "structure, sequence, and organization" of that declaring code. In the final stages of this case, Google was not accused of copying any implementing code. The parties in the case acknowledged that Google wrote its own implementing code for Android.

The declaring code is what most people would refer to as an API; not the court's definition of an API that combines the declaring code and implementing code. The declaring code is, in essence, a "software interface" allowing access to a software module's various methods. Said another way, it allows one software module to interface, pass information to/from, and control another software module.

I will refer to the declaring code as a "software interface," as that is what concerns the industry in this case. Software interfaces under this definition exclude any implementing code.

Now, with that out the way….

Here is a more detailed explanation of what the Supreme Court case specifically means.

Google was accused of copying certain declaring code of Java SE for use in Android. Not only did it copy the names of many of the methods but, in doing so, it copied the structure, sequence, and organization of that declaring code (e.g., how the code was organized into packages, classes, and the like). Structure, sequence, and organization (SSO) may be protectable under US copyright law. This case bounced around the courts for many years, and the history is fascinating for legal scholars. However, for our purposes, I'll just cut to the chase.

If a work is not protected by copyright, then it generally may be used without restriction. Google argued strenuously that the declaring code it copied was just that—not protectable by copyright. Arguments to support its non-copyrightability include that it is an unprotectable method or system of operation that is clearly written in US copyright laws as outside the scope of protection. In fact, this is an argument Red Hat and IBM made in their "friend of the court" brief filed with the Supreme Court in January 2020. If the court held that the declaring code copied by Google was not copyrightable, this would have been the end of the story and the absolute best situation for the developer community.

Unfortunately, we did not get that from the court, but we got the next best thing.

As a corollary to what I just said, you may get yourself in legal jeopardy by copying or modifying someone else's copyrighted work, such as a book, picture, or even software, without permission from the copyright owner. This is because the owner of the copyrighted work has the exclusive right to copy and make changes (also known as derivative works). So unless you have a license (which could be an open source license or a proprietary license) or a fair use defense, you cannot copy or change someone else's copyrighted work. Fair use is a defense to using someone's copyrighted work, which I'll discuss shortly.

The good news is that the Supreme Court did not rule that Oracle's declaring code was copyrightable. It explicitly chose to sidestep this question and to decide the case on narrower grounds. But it also seemed to indicate support for the position that declaring code, if copyrightable at all, is further from what the court considers to be the core of copyright.1 It is possible that future lower courts may hold that software interfaces are not copyrightable. (See the end of this article for a fuller description of this issue.) This is good news.

What the Supreme Court did instead is to assume for argument's sake that Oracle had a valid copyright on the declaring code (i.e., software interface) and, on this basis, it asked whether Google's use was a fair-use defense. The result was a resounding yes!

When is fair use fair?

The Supreme Court decision held that Google's use of portions of Java SE declaring code is fair use. Fair use is a defense to copyright infringement in that if you are technically violating someone's copyright, your use may be excused under fair use. Academia is one example (among many) where fair use can provide a strong defense in many cases.

This is where the court began to analyze each factor of fair use to see if and how it could apply to Google's situation. Being outside academia, where it is relatively easier to decide such issues, this situation required a more careful analysis of each of the fair-use factors under the law.

Fair use is a factor test. There are four factors described in US copyright law that are used to determine whether fair use is applicable (although other factors can also be considered by the court). For a fuller description of fair use, see this article by the US Copyright Office. The tricky thing with fair use is that not all factors need to be present, and one factor may not have as much weight as another. Some factors may even be related and push and pull against each other, depending on the facts in the case. The fortunate result of the Supreme Court decision is it decided in favor of Google on fair use on all four of the statutory factors and in a 6-2 decision. This is not a situation that was right on the edge; far from it.

Implications for software developers

Below, I will provide my perspective on what a software developer or attorney should consider when evaluating whether the reuse of a software interface is fair use under the law. This perspective is based on the recent Supreme Court ruling. The following should serve as guideposts to help you provide more opportunities for a court to view your use as fair use in the unlikely scenario that 1) your use of a software interface is ever challenged, and 2) that the software interface is held to be copyrightable…which it may never be since the Supreme Court did not hold that they are copyrightable. It instead leaves this question to the lower courts to decide.

Before I jump into this, a brief discussion of use cases is in order.

There are two major use cases for software interface usage. In the Google case, it was reimplementing portions of the Java SE software interface for Android. This means it kept the same declaring code and rewrote all of the applicable implementation code for each method declaration. I refer to that as "reimplementation," and it is akin to the right side of the diagram above used in the Supreme Court decision. This is very common in the open source community: a module has a software interface that many other software systems and modules may utilize, and a creative developer improves that module by creating new and improved implementations in the form of new implementing code. By using the same declaring code for each improved method, the preexisting software systems and modules may use the improved module without rewriting any of the code, or perhaps doing minimal rewriting. This is a huge benefit and supercharges the open source development ecosystem.

A second common use case, shown on the left side of the diagram, uses a software interface to enable communication and control between one software module and another. This allows one module to invoke the various methods in another module using that software interface. Although this second use case was not specifically addressed in the Supreme Court decision, it is my view that such use may have an even stronger argument for non-copyrightability and a fair-use defense in all but the most unusual circumstances.

4 tips for complying with fair use

Whether you are simply using a software interface to effectuate control and communication to another software module or reimplementing an existing software module with your own new and improved implementation code, the following guidelines will help you maintain your usage within fair use based on the Supreme Court's latest interpretation.

- For both use cases described above, use no more of the software interface than what is required to enable interaction with another software module. Also, be aware of how much of the work you are copying. The less you copy of the whole, the greater the weight of this fair-use factor bends in your favor.

- Write your own implementation code when reimplementing and improving an existing module.

- Avoid using any of the other module's implementation code, except any declaring code that may have been replicated in whole or in part in the other module's implementation code. This happens sometimes, and it is often unavoidable.

- Make your implementation as transformative as possible. This means adding something new with a further purpose or different character. In Google's situation, it transformed portions of Java SE to be better utilized in a mobile environment. This was seen as a factor in the case.

Can APIs be copyrighted?

So what about copyrightability of APIs and this odd situation of the Supreme Court not ruling on the issue? Does this mean that APIs are actually copyrightable? Otherwise, why do we have to do a fair-use analysis? Excellent questions!

The answer is maybe, but in my view, unlikely in most jurisdictions. In a weird quirk, this case was appealed from the initial trial court to the CAFC and not to the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals, which would have been the traditional route of appeal for cases heard in the San Francisco-based trial court. The CAFC does not ordinarily hear copyright cases like Oracle v. Google.2 While the CAFC applied 9th Circuit law in deciding the case, the 9th Circuit should not be bound by that decision.

There are 13 federal appellate courts in the United States. So although the CAFC (but not the US Supreme Court) decided that software interfaces are protected by copyright, its decision is not binding on other appellate courts or even on the CAFC, except in the rare circumstance where the CAFC is applying 9th Circuit law. The decision, however, could be "persuasive" in other cases examining copyrightability in the 9th Circuit. There is only a very small subset of cases and situations where the CAFC ruling on copyrightability would be binding in our appellate court system.

But even if the CAFC hears a case on software interfaces based on 9th (or another) Circuit law and decides that a certain software interface is protected by copyright under such law, we still have this very broad and powerful Supreme Court decision that provides a clear framework and powerful message on the usefulness of the fair-use doctrine as a viable defense to such use.

Will your use of another's software interface ever be challenged? As I stated, reuse of software interfaces has been going on for decades with little fanfare until this case.

1. “In our view, ... the declaring code is, if copyrightable at all, further than are most computer programs (such as the implementing code) from the core of copyright.” Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., No. 18-956, (US, Apr. 5, 2021)

2. The CAFC heard the case only because it was originally tied to a patent claim, which eventually dropped off the case. If not for the patent claim, this case would have been heard by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

1 Comment