Let's get one thing straight up front: there's nothing open about the Star Wars franchise in real life (although its owner does publish some open source code). Star Wars is a tightly controlled property with nothing published under a free-culture license. Setting aside any debate of when cultural icons should become the property of the people who've grown up with them, this article invites you to step into the Star Wars universe and imagine you're a computer user a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…

Droids

"But I was going into Tosche Station to pick up some power converters!"

— Luke Skywalker

Before George Lucas made his first Star Wars movie, he directed a movie called American Graffiti, a coming-of-age movie set in the 1960s. Part of the movie's backdrop was the hot-rod and street-racing culture, featuring a group of mechanical tinkerers who spent hours and hours in the garage, endlessly modding their cars. This can still be done today, but most car enthusiasts will tell you that "classic" cars are a lot easier to work on because they use mostly mechanical rather than technological parts, and they use common parts in a predictable way.

I've always seen Luke and his friends as the science fiction interpretation of the same nostalgia. Sure, fancy new battle stations are high tech and can destroy entire planets, but what do you do when a blast door fails to open correctly or when the trash compactor on the detention level starts crushing people? If you don't have a spare R2 unit to interface with the mainframe, you're out of luck. Luke's passion for fixing and maintaining 'droids and his talent for repairing vaporators and X-wings were evident from the first film.

Seeing how technology is treated on Tatooine, I can't help but believe that most of the commonly used equipment was the people's technology. Luke didn't have an end-user license agreement for C-3PO or R2-D2. He didn't void his warranty when he let Threepio relax in a hot oil bath or when Chewbacca reassembled him in Lando's Cloud City. Likewise, Han Solo and Chewbacca never took the Millennium Falcon to the dealership for approved parts.

I can't prove it's all open source technology. Given the amount of end-user repair and customization in the films, I believe that technology is open and common knowledge intended to be owned and repaired by users in the Star Wars universe.

Encryption and steganography

"Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi. You're my only hope."

— Princess Leia

Admittedly, digital authentication in the Star Wars universe is difficult to understand, but if one thing is clear, encryption and steganography are vital to the Rebellion's success. And when you're in a rebellion, you can't rely on corporate standards, suspiciously sanctioned by the evil empire you're fighting. There were no backdoors into Artoo's memory banks when he was concealing Princess Leia's desperate plea for help, and the Rebellion struggles to get authentication credentials when infiltrating enemy territory (it's an older code, but it checks out).

Encryption isn't just a technological matter. It's a form of communication, and there are examples of it throughout history. When governments attempt to outlaw encryption, it's an effort to outlaw community. I assume that this is part of what the Rebellion was meant to resist.

Lightsabers

"I see you have constructed a new lightsaber. Your skills are now complete."

— Darth Vader

In The Empire Strikes Back, Luke Skywalker loses his iconic blue lightsaber, along with his hand, to nefarious overlord Darth Vader. In the next film, Return of the Jedi, Luke reveals—to the absolute enchantment of every fan—a green lightsaber that he constructed himself.

It's not explicitly stated that the technical specifications of the Jedi Knight's laser sword are open source, but there are implications. For example, there's no indication that Luke had to license the design from a copyright-holding firm before building his weapon. He didn't contract a high-tech factory to produce his sword.

He built it all by himself as a rite of passage. Maybe the method for building such a powerful weapon is a secret guarded by the Jedi order; then again, maybe that's just another way of describing open source. I learned all the coding I know from trusted mentors, random internet streamers, artfully written blog posts, and technical talks.

Closely guarded secrets? Or open information for anyone seeking knowledge?

Based on the Jedi order I saw in the original trilogy, I choose to believe the latter.

Ewok culture

"Yub nub!"

— Ewoks

The Ewoks of Endor are a stark contrast to the rest of the Empire's culture. They're ardently communal, sharing meals and stories late into the night. They craft their own weapons, honey pots, and firewalls for security, as well as their own treetop village. As the figurative underdogs, they shouldn't have been able to rid themselves of the Empire's occupation. They did their research by consulting a protocol 'droid, pooled their resources, and rose to the occasion. When strangers dropped into their homes, they didn't reject them. Rather, they helped them (after determining that they were not, after all, food). When they were confronted with frightening technology, they engaged with it and learned from it.

Ewoks are a celebration of open culture and open source within the Star Wars universe. Theirs is the community we should strive for: sharing information, sharing knowledge, being receptive to strangers and progressive technology, and maintaining the resolve to stand up for what's right.

The Force

"The Force will be with you. Always."

— Obi-Wan Kenobi

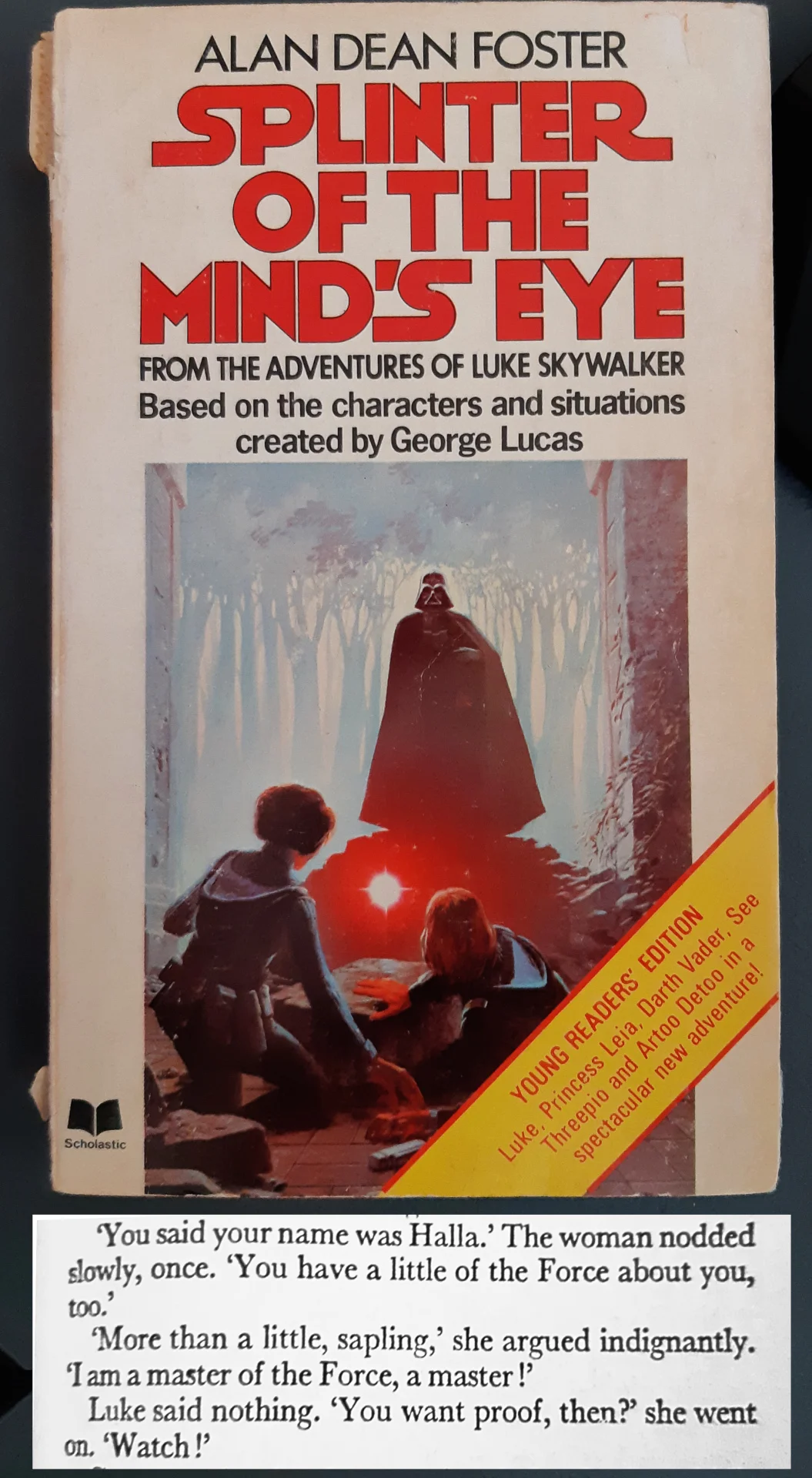

In the original films and even in the nascent Expanded Universe (the original EU novel, and my personal favorite, is Splinter of the Mind's Eye, in which Luke learns more about the Force from a woman named Halla), the Force was just that: a force that anyone can learn to wield. It isn't an innate talent, rather a powerful discipline to master.

By contrast, the evil Sith are protective of their knowledge, inviting only a select few to join their ranks. They may believe they have a community, but it's the very model of seemingly arbitrary exclusivity.

I don't know of a better analogy for open source and open culture. The danger of perceived exclusivity is ever-present because enthusiasts always seem to be in the "in-crowd." But the reality is, the invitation is there for everyone to join. And the ability to go back to the source (literally the source code or assets) is always available to anyone.

May the source be with you

Our task, as a community, is to ask how we can make it clear that whatever knowledge we possess isn't meant to be privileged information and instead, a force that anyone can learn to use to improve their world.

To paraphrase the immortal words of Obi-Wan Kenobi: "Use the source."

1 Comment