Classical computing is based on bits. Zeros and ones. This isn't because there's some inherent advantage to a binary logic system over logic systems with more states—or even over analog computers. But on-off switches are easy to make and, with modern semiconductor technology, we can make them very small and very cheap.

But they're not without limits. Some problems just can't be efficiently solved by a classical computer. These tend to be problems where the cost, in time or memory, increases exponentially with the scale (n) of the problem. We say such problems are O(2n) in Big O notation.

Much of modern cryptography even depends on this characteristic. Multiplying two, even large, prime numbers together is fairly cheap computationally (O(n2)). But reversing the operation takes exponential time. Use large enough numbers, and decryption that depends on such a factoring attack is infeasible.

Enter quantum

A detailed primer on the mathematical and quantum mechanical underpinnings of quantum computing is beyond the scope of this article. However, here are some basics.

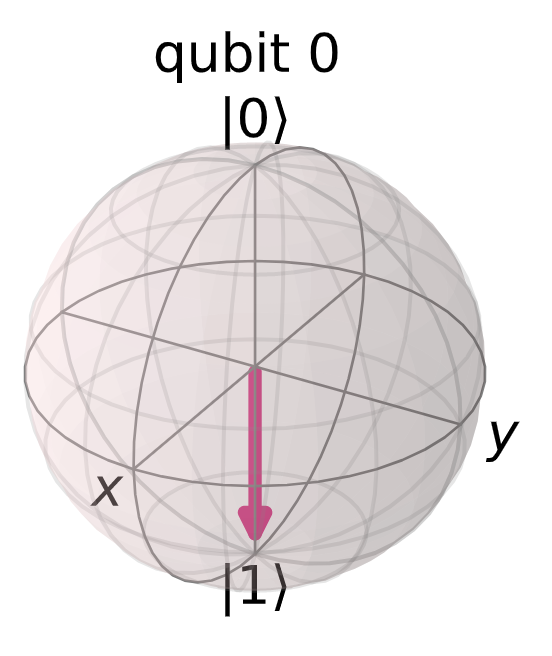

A quantum computer replaces bits with qubits—controllable units of computing that display quantum properties. Qubits are typically made out of either an engineered superconducting component or a naturally occurring quantum object such as an electron. Qubits can be placed into a "superposition" state that is a complex combination of the 0 and 1 states. You sometimes hear that qubits are both 0 and 1, but that's not really accurate. What is true is that, when a measurement is made, the qubit state will collapse into a 0 or 1. Mathematically, the (unmeasured) quantum state of the qubit is a point on a geometric representation called the Bloch sphere.

While superposition is a novel property for anyone used to classical computing, one qubit by itself isn't very interesting. The next unique quantum computational property is "interference." Real quantum computers are essentially statistical in nature. Quantum algorithms encode an interference pattern that increases the probability of measuring a state encoding the solution.

While novel, superposition and interference do have some analogs in the physical world. The quantum mechanical property "entanglement" doesn't, and it's the real key to exponential quantum speedups. With entanglement, measurements on one particle can affect the outcome of subsequent measurements on any entangled particles—even ones not physically connected.

What can quantum do?

Today's quantum computers are quite small in terms of the number of qubits they contain—tens to hundreds. Thus, while algorithms are actively being developed, the hardware needed to run them faster than their classical equivalents doesn't exist.

But there's considerable interest in quantum computing in many fields. For example, quantum computers may offer a good way to simulate natural quantum systems, like molecules, whose complexity rapidly exceeds the ability of classical computers to model them accurately. Quantum computing is also tied mathematically to linear algebra, which underpins machine learning and many other modern optimization problems. Therefore, it's reasonable to think quantum computing could be a good fit there as well.

One commonly cited example of an existing quantum algorithm likely to outperform classical algorithms is Shor's algorithm, which can do the factoring mentioned earlier. Invented by MIT mathematician Peter Shor in 1994, quantum computers can't yet run the algorithm on larger than trivially sized problems. But it's been demonstrated to work in polynomial O(n3) time rather than the exponential time required by classical algorithms.

Getting started with Qiskit

At this point, you may be thinking: "But I don't have a quantum computer, and I really like to get hands-on. Is there any hope?"

Enter an open source (Apache 2.0 licensed) project called Qiskit. It's a software development kit (SDK) for accessing both the quantum computing simulators and the actual quantum hardware (for free) in the IBM Quantum Experience. You just need to sign up for an API key.

Certainly, a deep dive into Qiskit, to say nothing of the related linear algebra, is far beyond what I can get into here. If you seek such a dive, there are many free resources online, including a complete textbook. However, dipping a toe in the water is straightforward, requiring only some surface-level knowledge of Python and Jupyter Notebooks.

To give you a taste, let's do a "Hello, World!" program entirely within the Qiskit textbook.

Begin by installing some tools and widgets specific to the textbook:

pip install git+https://github.com/qiskit-community/qiskit-textbook.git#subdirectory=qiskit-textbook-srcNext, do the imports:

from qiskit import QuantumCircuit, assemble, Aer

from math import pi, sqrt

from qiskit.visualization import plot_bloch_multivector, plot_histogramAer is the local simulator. Qiskit consists of four components: Aer, the Terra foundation, Ignis for dealing with noise and errors on real quantum systems, and Aqua for algorithm development.

# Let's do an X-gate on a |0> qubit

qc = QuantumCircuit(1)

qc.x(0)

qc.draw()An X-gate in quantum computing is similar to a Not gate in classical computing, although the underlying math actually involves matrix multiplication. (It is, in fact, often called a NOT-gate.)

Now, run it and do a measurement. The result is as you would expect because the qubit was initialized in a |0> state, then inverted, and measured. (Use |0> and |1> to distinguish from classic bits.)

# Let's see the result

svsim = Aer.get_backend('statevector_simulator')

qobj = assemble(qc)

state = svsim.run(qobj).result().get_statevector()

plot_bloch_multivector(state)

Bloch sphere showing the expected result. (Gordon Haff, CC-BY-SA 4.0)

Conclusion

In some respects, you can think of quantum computing as a sort of exotic co-processor for classical computers in the same manner as graphics processing units (GPUs) and field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs). One difference is that quantum computers will be accessed almost entirely as network resources for the foreseeable future. Another is that they work fundamentally differently, which makes them unlike most other accelerators you might be familiar with. That's why there's so much interest in algorithm development and significant resources going in to determine where and when quantum fits best. It wouldn't hurt to see what all the fuss is about.

Comments are closed.