In everyday life, I'm a web developer. Or, to be precise, I run a business that develops websites for a wide range of clients, from small businesses to large organizations. Every one of these sites comes with a CMS of some sort. Which CMS we use to develop the sites depends on a lot of factors, including what the client wants, the size of the website, and the required functionality. In this article, I'll cover the lessons learned when we developed our open source Bolt content management system.

Keep the customer in mind

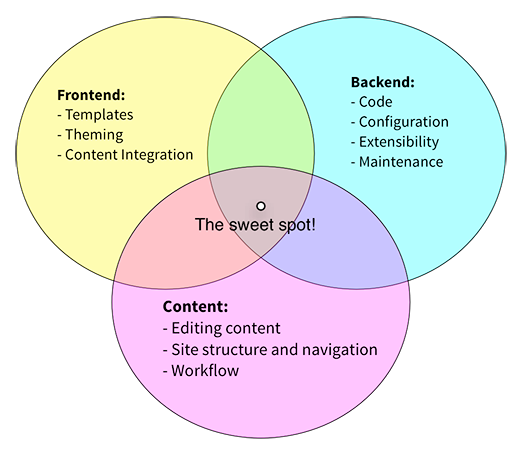

Often when working on larger site, you'll work with a small group of people with different job descriptions and skill sets. This overlap between people with different areas of expertise can cause some problems when interests collide:

- An editor doesn't want to know about database structures. They don't care if something is XML, JSON, or Mediumtext.

- The backend developer shouldn't concern themselves with the exact markup that's used on the website. <b> or <strong>, that's pretty much the same, right?

- Front end developers shouldn't need to know about scheduling new articles or whether or not the editor-in-chief has approved a change to an older article.

I strongly believe that there's no single CMS that's well suited to run all websites, and I'm always surprised that there are a lot of web development agencies that use the same CMS for every single project they do. If I were a client of an agency like that, I'd wonder if the CMS I'm getting is really the best fit for my website, or if it just happens to be the CMS they use for all their clients.

Because this is not how we would like to work, we've been looking around for CMSs that fit our workflow and, at the same time, complement each other. This way we have a few options to better help our clients without falling back to the same system every time. For most of the larger projects we develop, we use Drupal. It's a great system with a lot of functionality. Because of this, it's also a rather complex system (Especially for the editors, who eventually have to work in the system on a daily basis). We've done a lot of research to find a system that complements this: A simpler, more lightweight system for sites that don't require the extensive functionality offered by Drupal.

Every system that we've evaluated when looking for this had one or more major downsides. It seems like every single CMS out there is written by a certain kind of person for a certain kind of person. Because we couldn't find a system that really fit the needs of ourselves and our clients, we decided to develop our own. In doing so, we've learned a lot about what a good CMS should do, what it shouldn't do, and how to know the difference between these two options. This led us to develop our CMS called Bolt, and I invite you to check it out. It's pretty awesome, and for us it certainly fills a need in our daily work. But that's not what this article is about.

When developing our CMS, we've found that there are three main "audiences" for a CMS in general. Broadly speaking:

- Developers: These are the backend-developers. The people who install the CMS, configure it, and build any custom functionality.

- Implementors: These are the "frontend developers". The people who structure the content, set up the contenttypes, and implement the theming of the website in HTML/CSS in the templating language provided by the CMS.

- Editors: These are the people who work in the CMS on a daily basis. They write new content, edit existing pages, etc.

There's also a small group of people who are slightly outside of this group, namely the decision makers. The people who decide which CMS will be used for a project, and then hand it over to the developers to make it happen. These people—although important in the process—are not really part of the audience of the site or the CMS.

As it turns out, most CMSs focus strongly on one of these audiences, and thereby neglect the others to a degree. This has been bugging me for years now—Most well-known CMSs excel in one of these areas, but never in all three.

People who work with content a lot are usually people who are good with words—writing is what they're good at. Often, they work best and most efficiently when the CMS gets out of their way as much as possible. Every action they need to take, every extra button to click, and every choice to make is something that might break the flow of their work.

At the same time, the back-end developers are usually very technically proficient. These people know how databases work, and have a good understanding of what happens on servers. Because of this, this group has a good understanding of what happens under the hood of the CMS, and they prefer configuration over convention.

The front-end developers who do the implementation are usually knowledgable in what makes a good website—structure, navigation, usability—but they often also have the skill to implement the design in proper HTML and CSS.

These people with different skill sets need to work together to build one coherent, solid, good-looking website that works well and is easy to navigate. It's often very hard to place yourself in somebody else's shoes, so it requires discipline for this to work well.

By definition, the people who create the CMS are people who fall into the back-end developer category. It turns out that a lot of CMSs out there are obviously developed by programmers and for programmers. While this makes it easy to get a site up and running quickly, it might be met with resistance from the editors and the front-end developers.

Similarly, if the choice is made to use a certain well-known CMS with a very end-user focused interface, it's likely that the back-end developers will revolt because they predict there will be issues with future updates, scalability, and the development of custom modules.

Don't get me wrong, nobody is to blame here. It's just that we can not expect every user to judge a system by the same standards. What is critical in one person's judgment of a system might seem completely irrelevant to another.

This is what makes building a CMS hard: You, as a developer, might be able to build the most secure, most reliable, and most elegantly coded CMS, but if the editors don't understand how it works it's not going to be considered a success.

On the other hand, if you deliver the sloppiest code ever, but it provides the editors with exactly what they need, they will love it. At the same time, you will feel like you've done a crappy job for delivering that. The trick is to find a good balance in these things, and this leads to the next big lesson.

Avoid complexity

I've mentioned it earlier: a lot of CMSs are too complicated and too complex. The root of this problem is that it's really, really, hard to build something that's easy. It might sound like a given, but the best way to prevent something from becoming too complicated is to make a deliberate choice to keep something simple and to make sure it stays that way.

When a CMS evolves, it usually comes with more options and more features, which inherently leads to the users having too make more choices and to take more steps to do basic actions.

When you're developing a CMS (or a module for a CMS), you will often have to make choices on how to provide a specific bit of functionality to users. You might be tempted to say "Let's just make it an option for the end user," but this forces your users to make the choice. As mentioned above: Every time you present a choice to a user, they'll have to stop what they're doing for a short while in order to decide. There's a chance they lose concentration, and it might take them a short while to get back in the flow. This is a good example of a situation where you, as a developer, think you're providing a service to your users by giving them an option. In a lot of cases, it's better to pick the better option yourself to keep your users' workflow more straightforward. For more information about this, you should read Your app makes me fat.

Be consistent

Consistency is important when it comes to product development. The consistency of a product makes the difference between having it feel like a polished, well rounded experience, and having something that feels like it can break apart at any moment.

This is not something that's easily measurable or quantifiable, but it is something your users will notice.

There are three important aspects to keep in mind when you want to keep your product consistent:

- Dare to say no. Don't just do things because you _can_. With every new feature you should ask yourself if people really need this, and if it will not add more complexity for other users.

- Don't make assumptions about what users want or need. If they want something, they will absolutely let you know. It's much better to deliver a product that leaves people wanting more, than it is to have features that are never used.

- Have "sensible defaults". This is of course a very vague notion, but in general: If it's obvious to do something in a certain way, just do it that way. Don't add options for something obscure, or just to be quirky or different.

Be ready to say "no"

To put it simply: Saying no is important. If you don't say no enough, your product will lose its focus and consistency in the features it provides.

In practice, this happens a LOT. Not just in CMSs, but in all areas of software development. For example, Spotify used to be a perfectly fine music player, but over the years all kinds of social features and other silliness was introduced. I don't know anybody who prefers the current version of Spotify over the old one.

Why does this happen so often? CMS developers often lose sight of one of their target audiences. This could be because they lack the ability to place themselves in the shoes of the other groups, or because the client lacks technical expertise and asks for the wrong features. Or perhaps the people in the marketing department have a very compelling reason to include some silly feature. Regardless of the reason, you should always try to keep the bigger picture in mind: Will adding a certain feature make the CMS as a whole more pleasant and easy to use? If the answer is no, you should reconsider adding the feature.

At the same time, you should always try to keep in mind those who are not affected by a specific feature or change. If you build a new feature that's for the benefit of a certain member of the team, but it somehow gets in the way of others who don't need that feature, that's not good.

It's often very hard to say no. Especially if you like the person requesting some feature, or just because you like building new stuff more than maintaining old code. All software developers know that feeling. The following article has a lot of good arguments that will make it easier to say no, without sounding like a stubborn basement-dweller: Product strategy means saying no

Conclusion

As I mentioned before: Making something simple is hard. Very hard. The best way to prevent things from slowly turning your project into a inconsistent and complicated mess is to always keep in mind who you're building your products for. This is equally true for when you're building a website in your CMS of choice, or when you're building the CMS itself.

Try to put yourself into the shoes of the people you're doing it for, and keep the long-term goals in mind: Build a consistent product or website that appeals to all of your users. Keep them happy and they will continue using your products.

CMS

This article is part of the The Open CMS column coordinated by Robin Muilwijk. Share your stories about working with open source content management systems (CMS) and platforms like Drupal, Joomla, Plone, WordPress, and more.

1 Comment