Growstuff is an open source project to build a crop database from growers' knowledge, crowdsourcing information about who plants what food, when and where they plant it, and how they harvest it. Find it on GitHub.

Let's not think about how open source can change the world of food. Let's think about how open food can change the way we approach technology.

Agriculture is one of the world's most ancient technologies as well as humanity's most established open culture.

Only in the last decades in Western countries has it become closed. Since industrialisation, and especially since the intensification brought by synthetic fertilizers in the mid 20th century, we've become distanced from the technology that brings our food from field to table. Few people now know the steps to turn a chicken into a McNugget, or a tomato into ketchup—just as few know how to write their own software, or care about having the freedom to do so.

Nevertheless, agriculture continues along traditional lines throughout much of the world. Even in developed countries small-scale growers, heritage breeders, and organisations such as seed banks, community gardens, and slow food groups continue to openly share food knowledge within their communities. The open source community can learn from existing food movements. They are some of the longest-running open communities in the world, with a level of diversity and experience in grassroots organising that should be the envy of most open source projects.

Open data from the world's food growers

In 2012, Alex Bayley gave a keynote speech about what open source can learn from other open communities, including mostly-offline ones like seed banks and community gardens. Another speaker, GNOME founder Federico Mena Quintero was thinking along similar lines: he was making connections between open source and peer production in communities such as Permaculture and the traditional woodworking scene. Living in Mexico, Federico had trouble finding gardening advice to suit his local climate, and approached Alex for suggestions of where to find open crop data. Unfortunately, most available data was US-specific or aimed at broad-scale agriculture or scientists. Even if the data had been suitable, there was no way to connect the disparate data sets together into something a backyard gardener could use.

Top-down open data, from governments and other large organisations, seldom serves niche needs and can't address the needs of a diverse food community. If we want useful open food data, we need crowdsourcing, peer-to-peer networks, and distributed approaches. Open food projects need to be bottom-up endeavours, reflecting the diversity of the food system itself—a diversity that the UN recognises will lead us to a more sustainable future than larger, centralised efforts.

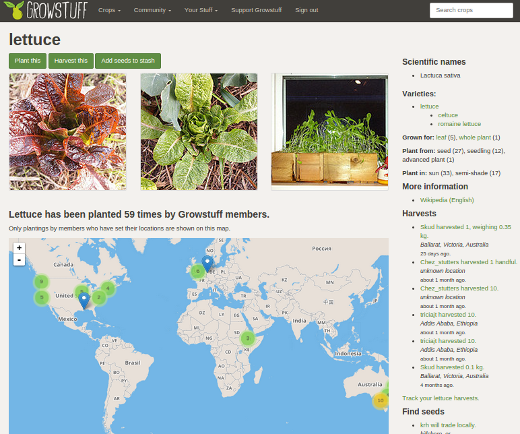

This realisation led Alex to create Growstuff, an open source project to build a crop database from growers' knowledge: crowdsourcing information about who plants what food, when and where they plant it, and how they harvest it. Growstuff recognizes that food-growing knowledge, such as planting times, suitable crops for microclimates, and pest identification, already exists inside the heads of growers around the world. This knowledge is hard to access unless you already have good social connections with your local growing community. Growstuff helps aggregate local growing information and build connections between growers, to encourage small-scale agriculture worldwide.

Welcoming a diverse food community

Open source food projects must connect to the wider, non-technical open food world. Food people and organisations share a huge body of domain knowledge, gathered through careful practice and observation over time. We need to meet them where they are, to be familiar with their language, practices, and conceptual frameworks, and to bridge the gap between our two worlds with mutual respect and collaboration. The open source community can be unwelcoming, elitist, and jargon-laden; we need to resist this, and make our open food projects inclusive and approachable for people with food skills as well as tech skills.

Open source's gender problem is particularly urgent here, as women produce more than half the world's food. As a project, Growstuff started with the premise that there is a lot to learn from existing food communities. From day one, the project was designed to include growers as well as coders, and to focus as much on transparent communication as on code. The result is a project with a notably diverse contributor base with members across six continents and a crop database that reflects a wide range of food cultures. It's easy, as technologists, to make assumptions about the way food should work. But, food is culture as much as it is technology. A scientist sees crops as species, and a gardener or cook knows that kale, brussels sprouts, and broccoli are all distinct vegetables even if they share a binomial name.

An open food ecosystem

Our projects need to interoperate, too. The open food puzzle is strongest when the pieces are all connected together. Groups like the Open Food Foundation are helping food projects connect with each other and discuss how we can collaborate on code, data, and strategy. At present, simply identifying active projects and understanding their place in the ecosystem is one of our biggest tasks. Part of our work is to encourage open food projects to provide open APIs and data, to use widely accepted licenses, and to work together on some of the key aspects of interoperability, such as linking food crops and products between projects. One measure of success will be when we can track food from planting to consumption, through connected applications like Growstuff for growing food, Open Food Network for food distribution, OpenFoodFacts for nutrition, and so on.

Empowerment, not disruption

As technologists, we have an urge to "disrupt" existing industries, but the food world has already been badly disrupted by intensive commercial agriculture and all its attendant problems. Let's look instead at using technology, and the open source community's established experience with distributed online collaboration, to empower food producers and consumers and to strengthen the food community's existing work. While we're at it, let's open ourselves up to disruption and see what improvements humanity's longest-running open community can bring to open source software.

This article was co-authored by Alex Bayley.

1 Comment