Dozens of new self-tracking wearable devices appear every month. They target health and quality of life applications, from sleep to physical activity. And, they are packaged as smart watches or as standalone pieces, launched under the umbrella of startups and industry leaders alike. Currently, there is no shortage of thoughtfully designed wearable devices promising to improve our health and quality of life, but amidst the ongoing technological deluge—do you think the future will be wearable or anti-wearable?

With major players such as Qualcomm rushing in to clear away the fad clouds, and in the aftermath of CES 2015, one is led to think that self-tracking using wearables is the next big thing, right? Think again. Wearables are nice, but have their share of inconveniences; we need to remember to wear them, they need to be frequently recharged, they may cramp up our style, and when too many are worn simultaneously, we end up looking more like a walking Christmas tree than a hip, cool techie.

The pros of wearable tech

Don’t get me wrong; self-tracking wearables have definitely worked out for me so far. When I first started using a Polar heart rate monitor a few years ago, it made a night and day difference between over-exhaustion and going uphill smoothly within healthy limits on my mountain bike.

If not for other reasons, open hardware projects and consumer devices for this space have had a truly transformative role in bringing knowledge, which would otherwise be bound to a hospital or clinical setting, to multiple aspects of our daily lives. Today we are increasingly empowered, more aware, and compelled like never before to check in on what’s going on with our body.

Still, most of us know our share of people that end up having their devices snugly forgotten in the back of a drawer. And we can all relate to the fact that we only get in-sync with our vitals when something is not quite right. Add to this discussion the latest news from projects like the Google Glass that point to a phasing out, and things become less than sharp for wearables. But is there a better solution?

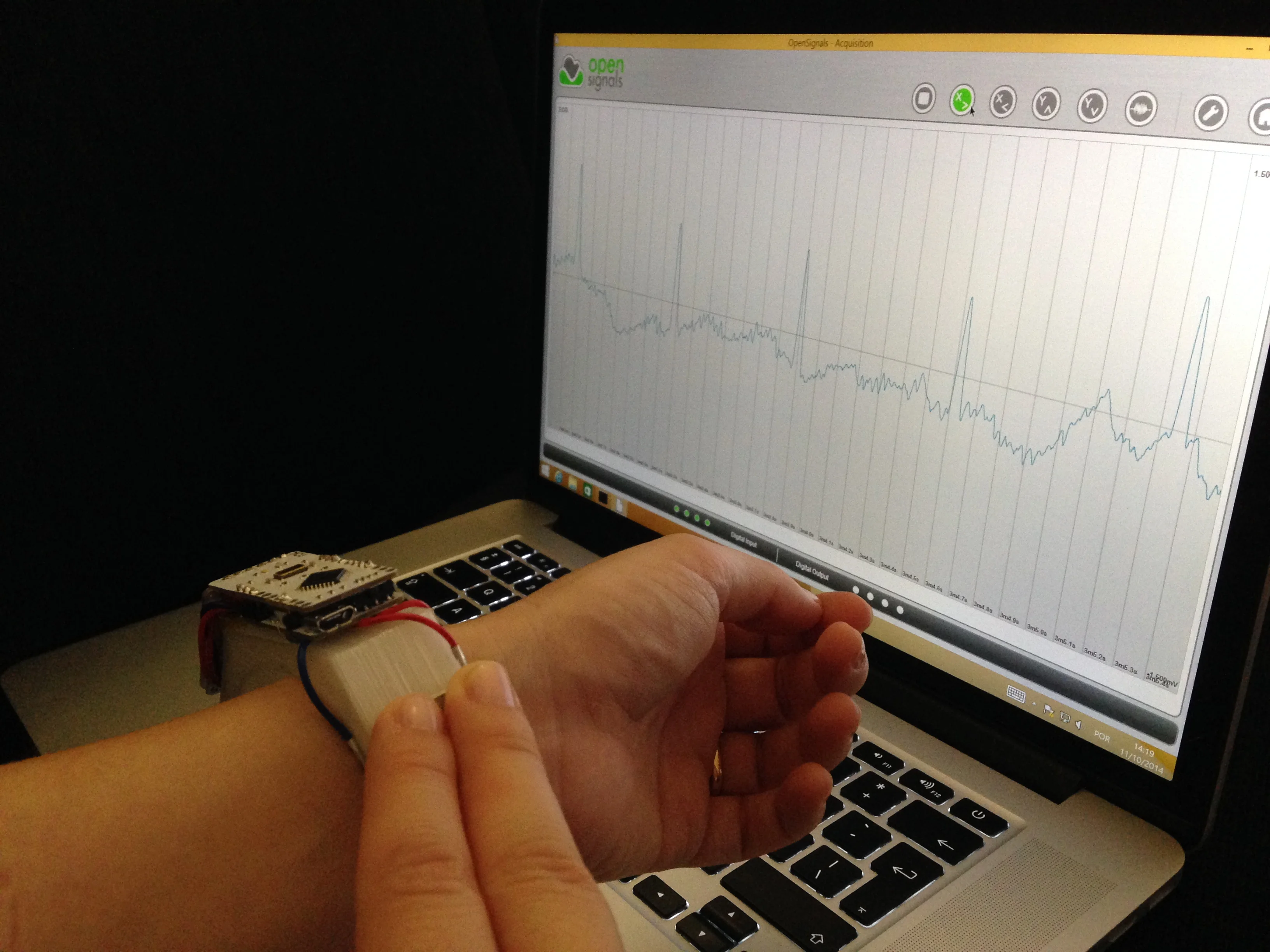

PulseCheck: Wearable bracelet created using open hardware that monitors your Electrocardiographic (ECG) signals in real-time.

The pros of anti-wearable tech

I believe that, as consumers, we generally tend to value practicality and peace of mind more than anything. Let’s face it, if using a device is too much trouble or a big change to our otherwise easy-going routines, chances are it’ll end up lying around more often than not even if our quality of life depends on it (of course I can only speak for myself).

This holds true for health and self-tracking as for any other things, and its where "anti-wearables" (or as MIT scholar and entrepreneur David Rose more gently refers to as 'enchanted objects') can make the difference. Anti-wearables are all about embedding health and self-tracking devices into the surrounding environment rather than the body of the user.

Although anti-wearables come with their fair share of challenges, the hype is already seeing its way through to consumer products. Some include:

- an app for contactless heart rate measurement, recently launched by Philips

- a computer keyboard that continuously monitors the ECG of the user, developed by CardioID (a startup company based out of Lisbon, Portugal)

- a car seatbelt for heart rate and respiration monitoring, developed by research center IBV together with biomedical engineering company PLUX and other partners

Existing open hardware tools now make it easy for anyone to greatly contribute to this change. For example, the team at BITalino recently completed a series of anti-wearable biohacking projects that resulted in things like a bicycle handlebar fitted with a 3-axis accelerometer and an Electrocardiography (ECG) sensor. The ECG sensor leads are connected to conductive textile electrodes on the left and right grips of the handlebar. Whenever the rider holds the grips with each of his/her hands, the data is streamed via Bluetooth to a smartphone that shows the heart rate.

BITalino on the MOOF: Open hardware BITalino-powered bicycle handlebars that monitor your heart rate without requiring a chest strap (the electronics are on the frame just to showcase the underlying hardware being used).

Wearable vs. Anti-wearable

Long story short, both have their place in our lives. We will surely continue to value the inputs from wearable devices when we’re jogging, exercising in the gym, or doing other free-moving activities. The trend, however, will be to see more and more everyday objects sporting health and self-tracking sensors on them. Alongside all the work being done around big data, anti-wearables make self-tracking more seamlessly integrated with, and a part of, our normal daily lives.

The pace of change is surely due to increase fueled by the open source community, as open hardware for biomedical sensing becomes more readily available. Projects like BITalino, OpenBCI, and others, are contributing to get this expertise out of the hands of a few medical device companies and to empower hundreds of creative and enthusiastic makers and developers around the world.

Why does this matter? Let’s consider cardiovascular diseases for example; according to the World Health Organization (WHO), this is the leading cause of death worldwide both in developed and developing countries. Whereas today one only seeks medical attention sporadically or only when things go wrong, in a near future anti-wearables will lead to things like mobile phones, TV remote controls, car steering wheels, and many other items that act in a preventive way, automatically alerting you to changes in your normal vitals.

Hardware

Connection

This article is part of the Open Hardware Connection column coordinated by Jason Hibbets. Share your stories about the growing open hardware community and the fantastic projects coming from makers and tinkers around the world by contacting us at open@opensource.com.

1 Comment