Open source and crowdsourcing—uttering these words at a meeting of the United Nations before the year 2010 would have made you persona non grata. In fact, the fastest way to discredit yourself at any humanitarian meeting just five years ago was to suggest the use of open source software and crowdsourcing in disaster response. Then, a tragic earthquake occured in Haiti in 2010, and OpenStreetMap and Ushahidi were deployed in the aftermath.

Their use demonstrated the potential of free and open source crowdsourcing platforms in humanitarian contexts.

Then, Typhoon Ruby in the Philippines occured five years later. What technology was used?

Initially a high-end Category 5 Hurricane, Typhoon Ruby was racing westwards on a direct collision course with the Philippines in December 2014, so the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN/OCHA) activated the Digital Humanitarian Network (DHN). The DHN serves as the official interface between established humanitarian organizations and tech-savvy, digital volunteer groups from all over the world. These Digital Humanitarians aid workers on the ground by making sense of the big data, like satellite imagery data and information from social media, that is generated during major disasters. Both of these data sources can be used to rapidly assess disaster damage and the resulting needs.

Requests from the UN

The UN asked the DHN to look for tweets related to urgent needs in the aftermath of Typhoon Ruby, so we used a free and open source platform called MicroMappers. MicroMappers is a joint QCRI initiative with UN/OCHA used to analyze the social media reports. MicroMappers combines crowdsourcing and artificial intelligence (AI) to make sense of tweets, Instagram pictures, YouTube videos, satellite imagery, and aerial imagery (captured using UAVs).

In short, MicroMappers is an experimental, open source AI platform powered by crowdsourcing. Why take a hybrid human and machine computing approach? Because that’s what it takes to win with big data. More than a million Instagram pictures and 20 million tweets were posted during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. We know from peer-reviewed scientific research (here and here, for example), that social media can accelerate the initial assessment of disaster damage and needs.

Finding the tweets and pictures that are most relevant to relief efforts is like looking for a needle in a growing haystack of information. And, time is a luxury that humanitarians do not have during disasters. It would take one person six years to read each tweet posted during Hurricane Sandy. Of course, if you had 60,000 volunteers, then it would only take about an hour to search through those 20 million tweets. But is 60,000 hours really the best use of human time if computers can do most of this filtering?

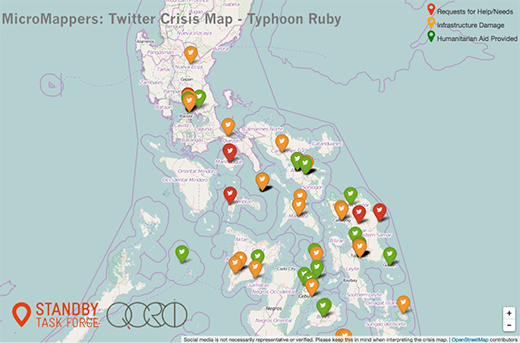

MicroMappers uses crowdsourcing to train algorithms in real-time to automatically identify tweets relevant to aid workers on the ground. The AI component of MicroMappers is called AIDR. Thanks to AIDR/SMS, MicroMappers can also classify SMS/text messages automatically. See this map of relevant tweets:

The UN also asked us to analyze pictures following Typhoon Ruby. More precisely, we were asked to identify all of the pictures posted on Twitter that showed disaster damage, and to rate the level of damage in each picture, then to map the pictures with the most damage.

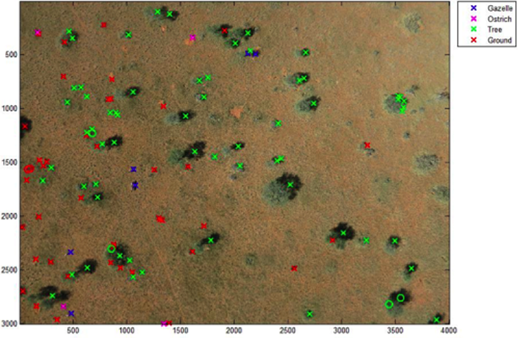

We used MicroMappers to crowdsource this task. And, we’re now looking to collaborate with computer vision experts to automatically identify pictures and videos that show disaster damage. We’re also looking to do the same with satellite and aerial imagery. In fact, we’ve already made some progress with the latter. A few months before Typhoon Ruby, we deployed MicroMappers to support wildlife protection efforts in Namibia. Rangers at the Kuzikus Wildlife Reserve had obtained tens of thousands of aerial images for the reserve in order to carry out a population survey of their wildlife. Because these rangers need to be out in the bush to protect endangered animals like the rhino, it would have taken them months to review all the imagery.

It took MicroMappers less than 24 hours, as noted in this CNN article.

Saving animals in disasters

Our research partners at EPFL, a polytechnic in Switzerland, took the crowdsourced results of the Namibia project and created machine learning classifiers that can automatically identify gazelles, for example, and other animals. (Read more on this research here.) Today, we’re working with computer vision experts to accelerate the process to automate the conversion of crowdsourced results to algorithms for real-time feature detection.

The end product for MicroMappers is a multi-layered map that displays the results of the semi-automated filtering of tweets, pictures, videos, satellite imagery, and aerial imagery integrated into one MicroMap.

The end product for MicroMappers is a multi-layered map that displays the results of the semi-automated filtering of tweets, pictures, videos, satellite imagery, and aerial imagery integrated into one MicroMap.

Previous peer-reviewed scientific studies (like this and this) have clearly demonstrated the value of data-integration for disaster response. To be sure, aerial imagery and other geo-data can substantially enrich social media layers during disasters thus providing additional context for rapid damage and needs assessments.

The future of disaster relief

We still have a long way to go with MicroMappers, and we are always looking to collaborate with new partners. Please get in touch if you’d like to join the team and work directly with the United Nations.

There’s a lot you can contribute to as a software developer. In the meantime, we’re busy making all our code more readily accessible and contributable via GitHub.

Why have we been working so hard on this free and open source crowdsourcing platform? Because it is absolutely unique. It's the only one of it’s kind in the humanitarian technology space and totally on the cutting-edge of next generation humanitarian solutions. Plus, MicroMappers is a formal, joint project with the United Nations—they’re the ones who (literally) called us up in 2013 and expressed the need for a platform like MicroMappers. They’re the ones who activate the Digital Humanitarian Network when they urgently need help to carry out more rapid damage and needs assessments. We don’t deploy MicroMappers because we feel like it or because we suspect it may potentially have impact; we only launch MicroMappers when the UN and others clearly articulate an urgent need and provide compelling evidence that the use of the resulting data will have impact.

The rise of Digital Humanitarians and the impact they continue to have using open source networks and software is vitally important, and thus, the subject of my new book. You too can be a Digital Jedi and make a difference. If you are a developer, a UI/UX guru, or QA, we are seeking your help on various projects. Please check MicroMappers on GitHub. Thank you in advance!

FOSS

This article is part of the HFOSS column coordinated by Jen Wike Huger. To share your projects and stories about how free and open source software is making the world a better place, contact us at open@opensource.com.

Comments are closed.