There are several minor tools and applications out there that keep popping up in my toolkit. You might not call any of them "killer apps," but darn it, they're fun to play around with and they sometimes take you in interesting directions. Some are creative and encourage productivity, and others just inspire creativity. Some are just plain silly.

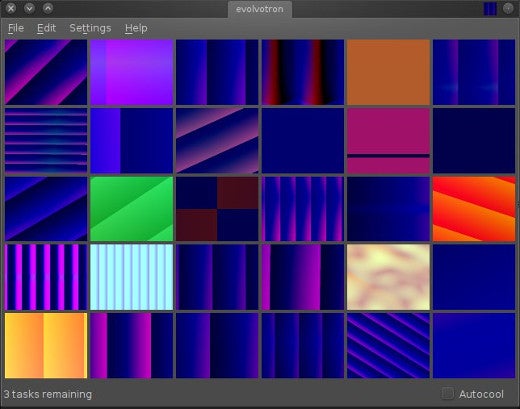

Evolvotron

Do you like generative art? Evolvotron!

Do you like unsolvable puzzles? Evolvotron!

Does the click of a mouse and blink of lights hypnotize you? Evolvotron!

Yes, Evolvotron is an interactive generative art application for Linux that forces the evolution of texture and pattern. Simply put, it's the lava lamp of Linux.

Fact is, a lot of cool things can be done with Evolvotron. As random and wacky as it might seem, it's obviously creating images through computation. Evolvotron gives you access to everything, and not just in the sense that it's open source software; it's packed with hidden options.

Using Evolvotron appears simple at first. You open the application and click. This loads random renders of graphical patterns in a six-by-five matrix. Click again and a new matrix is calculated and formed based on the cell that you clicked. You can click any cell; sometimes it's fun to follow the path of the deviations, other times it's fun to follow the constant seed, and still others a random selection of any given spawn takes you in unexpected directions.

That's the intro-level Evolvotron. The walk-in-the-park Evolvotron. But the pro Evolvotron artists (all three of them) bring in a little math.

The Settings menu of Evolvotron has several options that you can use to influence how Evolvotron generates its artwork. I have not traced back all the math in the source code, but from an artistic viewpoint, your options are:

- Mutation parameters: Set the percentage of deviation from the base image. You can set these values manually or you can use descriptors, such as Heat, Cool, Shield, Irradiate, and so on. You can also toggle the Autocool feature, which controls how long the mutation endures.

- Function weighting: Set the intensity of the mathematical functions at play. There must be at least a hundred functions spread across the Core set, plus Iterative, Fractal, Dilution, and more.

- Favorite function: Define (or leave un-defined) the function you prefer the root image to start with.

If you see an image that you particularly like, right-click on it. From there, you can spawn new versions of the image, lock it into place, analyze the function that generated it, or enlarge it and save it as an work of collaborative art between you and math.

Evolvotron is multi-threaded, but even so, some images may take longer than you expect to fully render. If you're trying to save an image and you get an error that it can't be saved yet, just be patient and save again later after the render is complete.

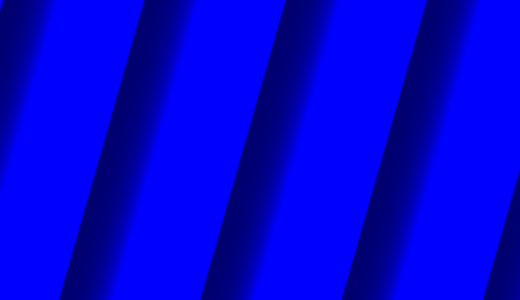

Fred's ImageMagick scripts

You know ImageMagick, whether you know it or not. It's the photo editor of the Unix shell; it processes images without the burden of a GUI interface. If you've ever uploaded a picture to an online forum or social network site and had the picture resized and cropped, you're quite possibly using ImageMagick indirectly.

Admittedly, it's probably not an afternoon's worth of fun to sit and run ImageMagick scripts on photos. But ImageMagick can be scripted, so it's trivial to run random ImageMagick functions on a directory full of photos overnight or during the day while you're away at work so that you can sit down at your computer and see what exciting accidental art you've managed to create.

To make that process a little less accidental, a guy named Fred Weinhaus maintains over 200 ImageMagick scripts available to use "for non-commercial use, ONLY." What gets defined as "commercial" is not terribly clear on his site (What if you don't intend to make money from using the script, but do? Can you make money from the resulting product of a script?), so their real-world usefulness depends on your interpretation of his restrictions (or your email correspondence with him, if in doubt).

However, as a fun diversion, the scripts definitely qualify.

Not all scripts are perfect, and not all produce the results you'll expect. They are easy to use, though, and being scripts, you can set them loose on a directory full of photos and come back hours later to sift through the results. Many scripts take quite a long time (they're complex!) and I haven't found a terribly graceful way to multi-thread them aside from launching dedicated processes.

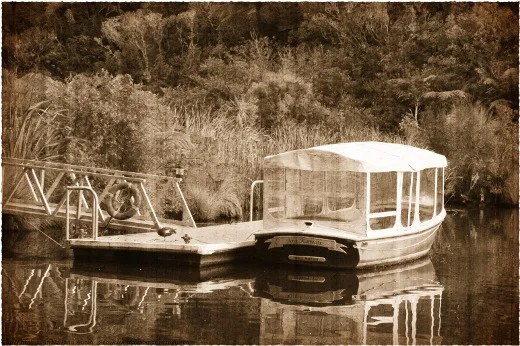

Each script has its own -help command, so for syntax consult the script you are running. Here's an example using the vintage3 script:

$ ./vintage3 -T torn -L 23 -B 33 -M 23 ./IMG_0559.JPG texture18.jpg oldboat.jpgIn this example, the options are placed at the front, with the input file plus a texture file (I use a picture of sand or dried mud to suggest film grain, but you can try anything), followed by the output target.

To "multi-thread" that on my desktop overnight on a directory, I just do something silly, like launching a separate command in three separate xterms (or rxvt tabs, if you prefer):

tab1_$ ./vintage3 -Blah blah blah ./IMG_???{0,1,2}.JPG texture18.jpg oldphoto-`date +%s`.JPG

tab2_$ ./vintage3 -Blah blah blah ./IMG_???{3,4,5}.JPG texture18.jpg oldphoto-`date +%s`.JPG

tab3_$ ./vintage3 -Blah blah blah ./IMG_???{6,7,8,9}.JPG texture18.jpg oldphoto-`date +%s`.JPGYou can also use GNU Parallel (although the syntax is a little more advanced than Bash commands cobbled together.)

The results are fun, and letting the photos process is a great way to spend CPU cycles that would otherwise go to waste. It's also a fun way to tax your computer for benchmarks and for learning more about photo manipulation.

Before:

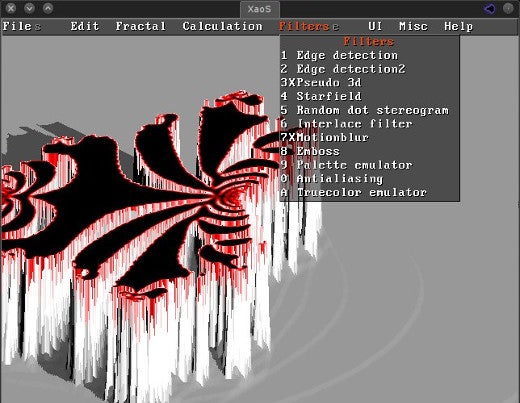

Xaos

Have you ever tried to explain to someone what a fractal is? It's really difficult to describe, and I've found that rough sketches on napkins rarely capture the awe and wonder that a good Julia set inspires. With Xaos, you can stop describing fractals to your friends and just show them.

Xaos is one of those curious applications that looks pretty simple at first and then surprises you with a whole hidden secret world of options. For instance, when you launch Xaos, the first thing you see is a fairly run-of-the-mill Mandelbrot set. When I first discovered Xaos, that was good enough for me; I'd been searching for a fractal generator for years, so finding an application that actually rendered a fractal for me was worth the price of admission into the Linux world for me. However, if you poke around for a few moments, you learn that clicking and dragging on the fractal moves you closer to it, dynamically rendering the intricate details of the shape as you get closer.

If that's not enough, you'll find myriad options bound to both the onscreen menu (visible only when the mouse cursor is hovered near the top of the Xaos window), and several hotkeys. For instance, you can create your own Julia sets on-the-fly by pressing j, or change the type of set to render from the Fractal > Formulae menu. But that's just technical options. Xaos is all about rendering fractals, so there are plenty of options to change how the fractal is presented; change from 2D to pseudo-3D, alter the colors, force constant rotation, enable autopilot to fly you along the fractal's paths, add motion blur, and enter VJ mode so you can manipulate and control Xaos without text rendering for public presentation.

Xaos in pseudo-3D mode.

Xaos in pseudo-3D mode.

Xaos is a fun and educational journey through fractal geometry. Try it out for fun, walk away a little smarter.

Netcat the band

With all this randomized art you'll be spending your time on, you'll want a little background music. Luckily, a geek-friendly band called Netcat released an album as a Linux kernel module on GitHub.

So, how exactly can an album be a kernel module? Well, the album, called Cycles Per Instruction, gets compiled into a kernel module (specifically, netcat.ko). When the module is added to your environment, it manifests itself as /dev/netcat. Piping the output of that "device" into a media player like ffplay plays the album.

If it sounds too amazing to be true, you're welcome to try it for yourself. The instructions are straightforward, but I'll reiterate them here with a few notes:

$ git clone https://github.com/usrbinnc/netcat-cpi-kernel-module.git

$ cd netcat*module

$ make -j4

$ su -c 'insmod ./netcat.ko'

$ ffplay - < /dev/netcatI've successfully compiled and listened to this album on both a Linux 2.6.x series kernel and a 3.x kernel. The band's GitHub page recommends ogg123, but lately some users have reported playback issues. I found ffplay to solve the playback issue, but you can also try mpv, legacy mplayer, or others.

The album itself is beautiful. It's well worth a listen. It will, however, continue to play until you remove the module:

$ su -c 'rmmod ./netcat.ko'Open source randomness

There's so many more fun projects out there to explore, so don't let my modest list be the end of the adventure. Too often in the open source world, we suffer from people looking in, scrutinizing what we make, and seeking practical and clear paths toward monetization. But that's not what open source is about, really; open source is supposed to be fun and inspiring. It empowers everyone to follow their vaguest notion to completion, no matter how "useless" or "frivolous" it may be.

Take an afternoon or two and do something pointless. Have a go with a generative art application, write some code and see what it produces, play a geeky album, or make a geeky album. There are plenty of "toys" out there, and playing is what really drives innovation. Make some stuff and share it.

This article originally published in June 2016 and has been updated with new information.

Comments are closed.