When I became CIO at the University of Alabama at Birmingham in 2015, I confronted the same mandate every new IT leader faces when assuming the role: outlining, developing, and executing a strategic plan. The pressure to do this swiftly and immediately can be immense—and I think many CIOs feel compelled to articulate and hand down fully formed plans on Day 1. After all, that's typically the quickest way to assert your position and vision as a leader.

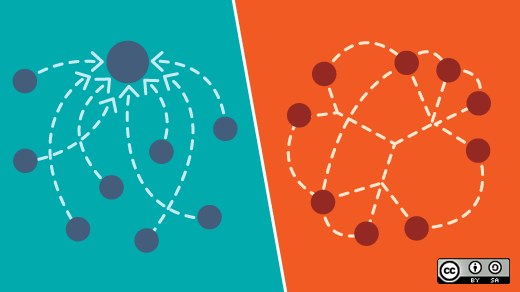

But I like to take a different approach. I don't dictate my team's initial goals. I open them up.

Working this way felt especially important in my new role at UAB, which I knew was going to be the last gig of my career. I wanted to make the largest contribution I could—not only to the university, but also to higher education in general.

What better way to do this than to let them openly contribute to the goals my team would be tackling during my tenure?

So I let the entire university community help me determine and prioritize our most pressing IT problems. The results were astounding, a perfect example of the benefits of taking an iterative, adaptive approach to this kind of development.

Let me share what happened.

Just a SPARK

My first day as CIO at UAB was June 1, 2015. That was also the day we launched a new, university-wide idea collecting and brainstorming platform. The platform (which we code-named "SPARK," in honor of UAB's mascot, Blaze the Dragon), was a crowdsource-style tool for collecting and surfacing the best ideas for ways IT could improve the lives of students, administrators, and faculty.

Anyone could use the platform to submit an idea. "Help us understand the issues you're facing and what would make the biggest difference in your life," we told anyone interested in participating. "You can submit an idea that anyone can comment on, and as long as you play nice, everything is in scope."

Our goal was ambitious but clear: Identify 100 potential "wins"—100 things we could do to improve university life—in 100 days, then implement all of them within a year.

Within the initiative's first 55 days, 386 users posted 73 ideas, made 367 comments, and cast 1,747 votes. (Keep in mind, too, that this activity was spurred almost entirely by word of mouth during the summer, when a sizable portion of the faculty and students aren't even on campus.) As a result, we became aware of issues and ideas like:

- Electronic signature of documents as part of moving to a paperless system

- One gigabit bandwidth to the desktop

- Technology training and certification for IT pros and IT consultants

- Unlimited storage for all students, faculty, and staff

- Orientation for new IT employees

And those are just a few. While the ideas were flooding in, my team and I were taking meetings—hundreds of meetings (collectively), including several town hall-style gatherings to solicit feedback from the university community in an open forum.

In the end, we amassed an unbelievable amount of data. How were we going to sort it so the best ideas could rise to the top?

Making sense of it all

We began by arranging our crowdsourced suggestions into four primary categories:

- Ideas that are great, but not directly applicable to the customer/community

- Ideas for solutions that were actually already available as part of our current IT infrastructure and resources

- Ideas that were clearly "quick wins," something we could implement in a day (or less)

- Ideas that were groundbreaking and needed to be rolled into a broader strategic plan with a longer timeline

Believe it or not, most of the ideas we received fell into the first three categories. So our list of priorities was already becoming clear.

At the same time, our team was working with the insightful feedback we'd gleaned from our in-person meetings. Using mind-mapping software, we charted common responses and pain points, and connected these to our broader strategic goals and imperatives. All senior members of the IT leadership team contributed to this effort.

With that, we'd found our 100 potential wins. And true to our word, we got to work acting on all of them within the year.

The results are in

I'm proud to report that we actually achieved 147 wins before the following June. I can't possibly recount all of them here. Many, however, were so startlingly simple—and yet so profoundly game-changing—that they seem almost laughably obvious in hindsight.

For example, take our approach to passwords on campus. Our policy really was outdated and ineffective, and we quickly learned that people disliked our approach to password security. So we modified aspects of it—first, our requirements for acceptable passwords (making them much stronger) and, second, our required interval for mandatory password changes (lengthening and aligning it with the operational rhythm of a university, so users needed to switch passwords less frequently). Members of the campus community appreciated these changes so much that they were literally hugging me on the street in gestures of pure joy—the first time in my career, I can honestly say, that's ever happened to me.

In line with another frequently received request, we worked diligently to increase the data storage limits for users on campus. This work seemed especially pressing—and the need so very obvious—when I learned from faculty researching Parkinson's disease that they weren't able to store all the high-resolution brain scans they needed to do their work efficiently and effectively. Once we removed their data caps, they told me they were finally able to spend more time seeking a cure for Parkinson's and less time sorting through data files to make space for new work.

As we were steadily chipping away at our 100-win checklist, people around the campus couldn't help but take notice. My provost threw my team a surprise party (complete with delicious cake) to celebrate our crossing the 100-win milestone. Even the most skeptical members of the faculty senate stood up and applauded my team at a budget meeting (and our fiercest critics began saying things like "Well, while I don't think this is going to last long-term, I'm suspending disbelief because you've demonstrated you can achieve results"). And in another career-first moment for me, I got to serve as an honorary coach during the opening home football game. That's really when I realized that our community now viewed the IT staff as trusted partners in campus innovation. How many other IT organizations get recognized on the football field?

Lessons learned

I learned some valuable lessons during those 100 busy days. Here are a few of the most valuable:

Trust the community. Opening a feedback platform to anyone on campus seems risky, but in hindsight I'd do it again in a heartbeat. The responses we received were very constructive; in fact, I rarely received negative and unproductive remarks. When people learned about our honest efforts at improving the community, they responded with kindness and support. By giving the community a voice—by really democratizing the effort—we achieved a surprising amount of campus-wide buy-in in a short period of time.

Transparency is best. By keeping as many of our efforts as public as possible, we demonstrated that we were truly listening to our customers and understanding the effects of the outdated technology policies and decisions that were keeping them from doing their best work. I've always been a proponent of the idea that everyone is an agent of innovation; we just needed a tool that allowed everyone to make suggestions.

Iterate, iterate, iterate. Crowdsourcing our first-year IT initiatives helped us create the most flexible and customer-centric plan we possibly could. The pressure to move quickly and lay down a comprehensive strategic plan is very real; however, by delaying that work and focusing on the evolving set of data flowing from our community, we were actually able to better demonstrate our commitment to our customers. That helped us build critical reputational capital, which paid off when we did eventually present a long-term strategic plan—because people already knew we could achieve results. It also helped us recruit strong allies and learn who we could trust to advance more complicated initiatives.

It's more work. Sure, acting alone to sketch a roadmap for my first 100 days would have been easier. But it wouldn't have generated the results the crowdsourced version did. Without a doubt, collaborative approaches like ours require more work than solitary, draconian ones. You'll need to think strategically and long-term. (Case in point: Launching SPARK on June 1 actually required three months of planning and development leading up to that critical day.) But if you really seize this opportunity to engage with your community, you'll realize better results.

Our yearlong lesson in community-focused crowdsourcing revealed the benefits that adaptive approaches to strategic planning can have for our organization. I'm sure they can do the same for yours.

This article is part of the Open Organization Workbook project.

Comments are closed.