The print-on-demand industry is one of my favorite products of technological innovation. It removes gatekeepers and eliminates the bottleneck of physical bulk production. It gives anybody with a good idea and the drive to produce it a way to get their work out into the world.

Print-on-demand combined with open source software is even more powerful, letting independent publishers generate content at whatever price they can afford at the time (or for nothing at all). And the tools are a pleasure to use.

This month, I present self-promotion, cleverly disguised as a case study, of a group of game designers (my creative team and me) using a fully open source stack to create, play test, and publish a tabletop fantasy battle card game.

Petition

I count among my hobbies tabletop gaming. I have designed adventures for role-playing games, I've designed gaming accessories like the Pocket Dice Roller, and I've developed homebrew rules for published games.

I spent the past year developing a game called Petition. In Petition, players build a society consisting of citizens, each of whom supports some number of pillars: art, military, religion, and industry. When a society grows strong enough, these citizens naturally try to spread their influence, dominating their other players. This happens in the form of a good, old-fashioned card battle, with players sending citizens in to battle to see which side is more influential. The winner steals the enemy's cultural pillar, and the game continues until one society is devoid of its own cultural identity.

In other words, it's human nature in the form of a frivolous fantasy game.

The central game mechanic, though, is the petitioning process, because in order for any player to attack another, they must petition for the favor of a god.

A player spends prayer beads and citizens to earn a god's support; however, any other player has the option to challenge a player's temple offering by bidding beads and citizens of their own. The catch is inspired by the classic prisoner's dilemma: A challenger can see how many beads have been offered, but the cards remain secret until all bids are in. The combination of beads and cards sways the gods in different ways, and the gods expect different actions based on what has been bid. It's a dangerous process and one that has thrown play testers into chaos over the past year.

Early development in Nextcloud

There are lots of ways to develop a tabletop card game, and none of them are wrong as long as you learn something from the experience. Most of the early game development for Petition happened in my head during my morning walk to the film studio where I was working. I kept the general idea, a fantasy battle game hinged upon the mechanic of petitioning a pantheon of gods for support, in the back of my mind, taking note of particularly good ideas on my Nextcloud instance while at work so that I could work them out later at home.

Specifically, I found the Notes app very helpful. With it, I could write notes about the game's mechanics, ideas about artwork, modifications to rules, and anything else that came to mind, and store the notes in a notebook-like file structure. The notebook was viewable in a web browser or on a mobile app, and Nextcloud makes it easy to share the notebook with my collaborator.

Once the rules were ironed out, I formalized them in a text document using Emacs. It was too early to consider layout, so I kept the format simple and just concentrated on getting the rules properly structured.

The initial rules were written for 2 to 4 players. Sometimes I design single-player rules first, then extend them out for multiple player, but this game is inherently competitive, so I wanted to concentrate on the battle mechanics. Because a key mechanic of the game is the petitioning process, I especially wanted to concentrate on the capriciousness of the players.

Mock-up in GIMP

For the early mock-up of my game, I downloaded Creative Commons tarot artwork because it looked appropriately fantasy-based. I also downloaded icons from openclipart.org. I did quick and dirty card design in GIMP.

opensource.com

The resulting deck of 108 cards weren't pretty, but they served their purpose as the game deck for the subsequent year of play tests.

Artwork with Krita

Once the game's ruleset was put through its paces, I contacted the Morevna Project, a group of filmmakers I support on Patreon, for a recommendation of an open source illustrator. They referred me to Nikolai Mamashev, an excellent illustrator working in Krita on Linux. I told Nikolai a bit about the game and left him to do what he does best: draw amazing pictures using open source tools. We agreed on a price per image, and I purchased a few initial cards from him.

opensource.com

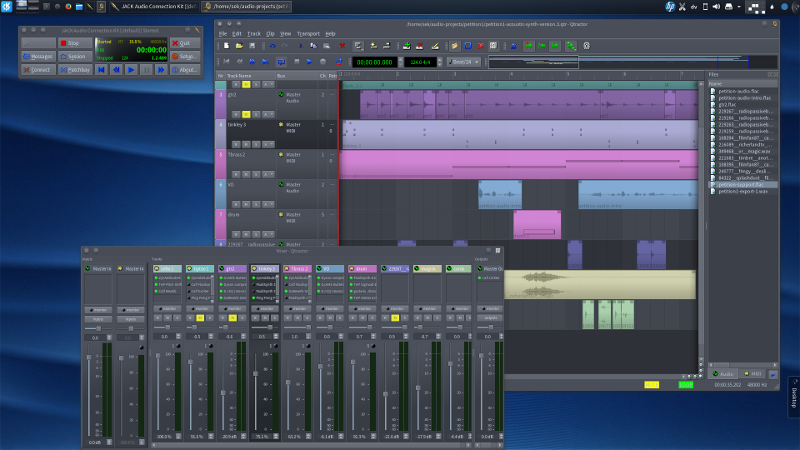

Video with Qtractor and Synfig

I wanted an animated video for promotional purposes. Eventually, this video will be expanded into a quickstart tutorial.

The first step was the soundtrack. I recorded a brief overview of the game into Audacity, then cleaned up the audio where necessary. I imported my vocal track into Qtractor and started composing background music according to the vocal queues.

opensource.com

When I compose, my method, mostly due to incompetence, is to play my initial ideas straight into Qtractor, then mouse what I actually meant to play based on what was captured. The tune went from a synth-heavy track to something acoustic back to synth, but eventually I reached something I liked enough to use.

Next, I worked on the video in Synfig. There are several good open source animation applications available (such as OpenToonz, Krita, and StopGo), but I chose Synfig because I know it well. Also, it doesn't model itself as a digital cell application, and I didn't plan on drawing anything myself. I just needed a good application to handle the movement and manipulation of sprites.

I animated mostly by frame count: I listened to my audio, made note of important frame numbers, and animated to hit those marks.

That took a few days, and when I was done I decided to insert a little bit of modest foley work. I grabbed sound samples, like the sound of a magical burst and the sounds of cards being dealt, from freesound.org. For precise placement, I could have counted frames, but I decided to take the high-tech route, using XJadeo to sync video playback with my soundtrack in Qtractor.

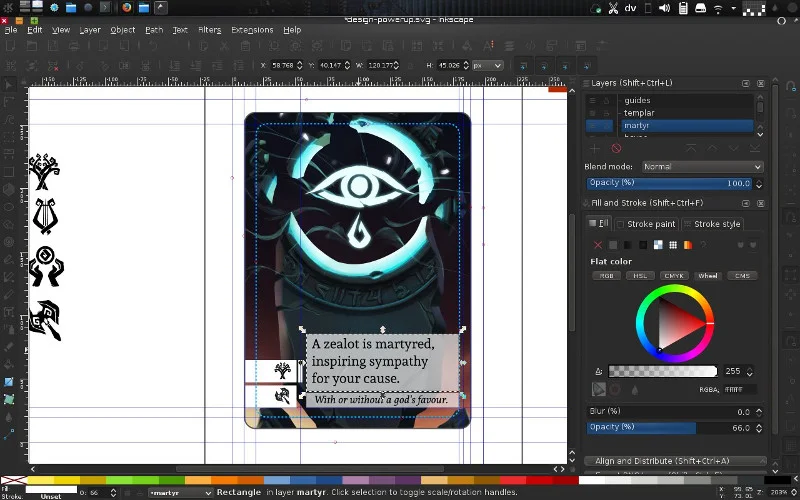

Card design with Inkscape

Although I don't yet have the funds for a full deck, I have enough cards illustrated to design the final look of the game. In my head, this game lives in the tradition of Magic: The Gathering, Munchkin, Dominion, and other great fantasy card games, but in reality it's probably more like fantasy Texas Hold'em, so I decided to keep the card design modest and simple.

In my original game, I had designed several "paragon" cards. These were cards that the players were meant to capture from one another. Each paragon also had a god associated with them, which was why players had to petition the gods before moving in for an attack: A god had to be persuaded by one paragon to attack another paragon who followed the same god. It made sense storywise, but in the play tests it just confused players because there were just too many human elements: gods, paragons, and citizens, all vying to tap into the same powers.

For the final design, I decided to reduce the paragons to icons. These icons were placed on each god card and each citizen card so that players could easily and quickly identify what card could aid in which kind of battle.

I decided to use Inkscape for the final card layout because I knew that there would be a lot of extra vector work on top of the artwork.

opensource.com

I downloaded a card template from the print-on-demand service that I decided I'd most likely use. For each card type, I created one Inkscape file with several layers. Each layer would hold one card. Since I don't have all the art yet, most layers are placeholders, but each card's name and attributes are complete in every layer.

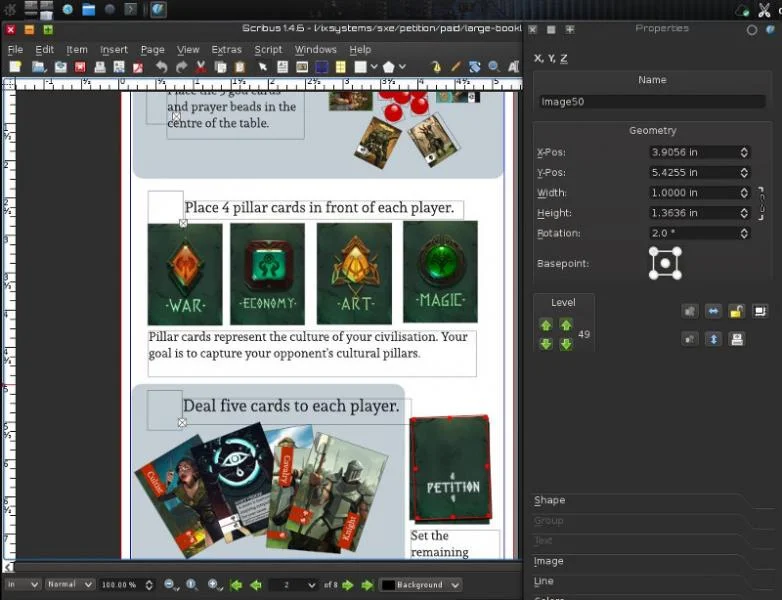

Rulebook with Scribus

Following my own advice about writing documentation like a board game, I wanted to refine the rules of the game. I wanted the rules to enable gameplay rather than be a barrier to it, so I decided to create a friendly, nonthreatening rulebook that would show people how to play, then get out of the way. I didn't want players to have to take a class in logic or game theory to understand my game.

I wanted my rulebook to have big, friendly pictures so that readers with less than stellar reading comprehension could piece together the rules—if not only from the pictures, then from keywords and pictures combined. I wanted the text to be minimal, so even strong readers wouldn't have to invest too much time getting through it, because there's nothing less fun than announcing to your friends that you want to introduce them to a cool new game you just bought, then spending the next 30 minutes deciphering codex.

In a way, my inspiration was the excellent Pathfinder Strategy Guide, an excellent intro to RPG character building by Paizo. It's the friendliest book about how to get started with RPG I've ever read, with lots of charts and pictures breaking down an impossibly complex subject into digestible sections based on when you need to know the information.

opensource.com

This principle changed everything, and Scribus made it easy to rearrange graphic elements and text as I simplified the delivery. Instead of explaining to the reader how to both petition and deal with challenges to a petition all in one go, I broke it down into sections that would apply conditionally based on what was actually happening. The docs assume that all petitions are successful when the mechanic is first introduced, and challenges are explained in a dedicated section that can be read after the petition mechanic has been internalized. This also makes referencing rules easier, because all exceptions are explained independently of when they actually happen; after all, a reader doesn't need to know why or when a challenge happens, they just need to know when a challenge can be made and where to look when a challenge happens.

There was a small snag while designing the booklet. The Scribus template provided by the print-on-demand service had the cut marks incorrectly placed by about 8mm. This didn't become evident until the proofing stage, so I had to go back into Scribus to account for the template's error. Scribus made it easy to make little modifications to fudge the content inward without losing the overall integrity of the design.

Scribus also has a surprisingly robust exporter. From previous experience with printers, I had anticipated exporting to PDF, which I knew Scribus did excellently. It turned out that this printer wanted all pages as PNG files instead. I anticipated exporting to PDF from Scribus, then using ImageMagick to convert to individual PNG files, but Scribus pleasantly surprised me with all the relevant options I could ever need for PNG export. It saved me a few steps, and I appreciated it, especially as I went back and forth from proofing to adjusting.

Creative commons

The entire project is licensed under the Creative Commons, and is being created with open source software. All of it assets are accessible to everyone.

Open source workflow

Open source software offers a full publishing workflow, from concept to graphics to layout, and it's available to everyone. Don't let the lack of a publisher get in your way: If you have an idea, create it.

2 Comments