Storytelling is an innate part of human nature. It's an idle pastime, it's an art form, it's a communication tool, it's a form of therapy and bonding. We all love to tell stories—you're reading one now—and the most powerful technologies we have are generally the things that enable us to express our creative ideas. The open source project Twine is a tool for doing just that.

Twine is an interactive story generator. It uses HTML, CSS, and Javascript to create self-contained adventure games, in the spirit of classics like Zork and Colossal Cave. Since Twine is largely an amalgamation of several open technologies, it is flexible enough to do a lot of multimedia tricks, rendering games a lot more like HyperCard than you might normally expect from HTML.

Installing Twine

You can use Twine online or download it locally from its website. Unzip the download and click the Twine application icon to start it.

The default starting interface is pretty intuitive. Read its introductory material, then click the big green +Story button on the right to create a new story.

Hello world

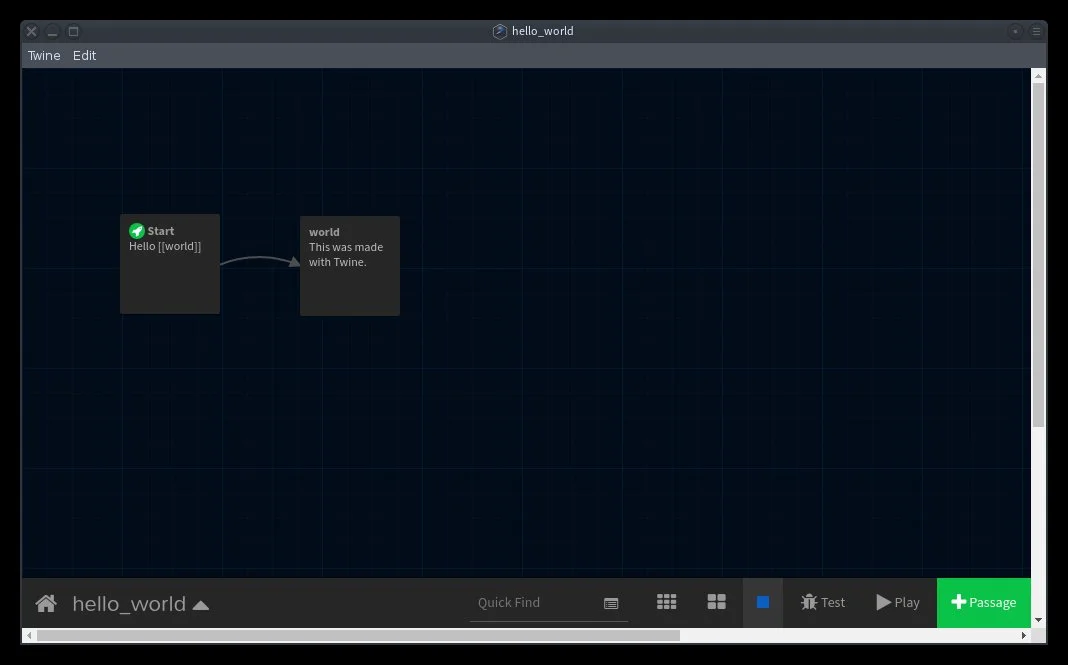

The basics are simple. A new storyboard contains one node, or "passage" in Twine's terminology, called Untitled passage. Roll over this passage to see the node's options, then click the pencil icon to edit its contents.

Name the passage something to indicate its position in your story. In the previous version of Twine, the starting passage had to be named Start, but in Twine 2, any title will work. It's still a good idea to make it sensible, so stick with something like Start or Home or init.

For the text contents of this story, type:

Hello [[world]]If you're familiar with wikitext, you can probably already guess that the word "world" in this passage is actually a link to another passage.

Your edits are saved automatically, so you can just close the editing dialogue box when finished. Back in your storyboard, Twine has detected that you've created a link and has provided a new passage for you, called world.

Developing a story in Twine

Open the new passage for editing and enter the text:

This was made with Twine.

To test your very short story, click the play button in the lower-right corner of the Twine window.

It's not much, but it's a start!

You can add more navigational choices by adding another link in double brackets, which generates a new passage, until you tell whatever tale you want to tell. It really is as simple as that.

To publish your adventure, click the story title in the lower-left corner of the storyboard window and select Publish to file. This saves your whole project as one HTML file. Upload that one file to your website, or send it to friends and have them open it in a web browser, and you've just made and delivered your very first text adventure.

Advanced Twineage

Knowing only enough to build this hello world story, you can make a great text-based adventure consisting of exploration and choices. As quick starts go, that's not too bad. Like all good open source technology, there's no ceiling on this, and you can take it much much farther with a few additional tricks.

Twine projects work as well as they do partly because of a JavaScript backend called Harlowe. It adds all the pretty transitions and some UI styling, handles basic multimedia functions, and provides some special macros to reduce the amount of code you would have to write for some advanced tasks. This is open source, though, so naturally there are alternatives.

SugarCube is an alternate JavaScript library for Twine that handles media, media playback functions, advanced linking for passages, UI elements, save files, and much more. It can turn your basic text adventure into a multimedia extravaganza rivaling such adventure games as Myst or Beneath the Steel Sky.

Installing SugarCube

To install the SugarCube backend for your project:

- Download the SugarCube library. Even though Twine ships with an earlier version of SugarCube, you should download the latest version.

-

Once you've downloaded it, unzip the archive and place it in a sensible location. If you're not used to keeping files organized or managing creative assets for project development, put the unzipped SugarCube directory into your Twine directory for safekeeping.

-

The SugarCube directory contains only a few files, with the actual code in

format.js. If you're on Linux, right-click on the file and select Copy. -

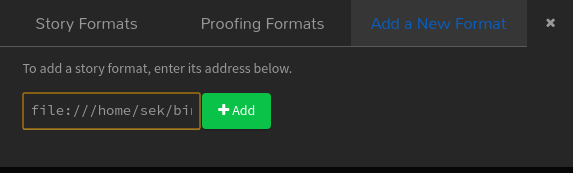

In Twine, return to your project library by clicking the house icon in the lower-left corner of the Twine window.

-

Click the Formats button in the right sidebar of Twine. In the Add a New Format tab, paste in the file path to

format.jsand click the green Add button.

Installing Sugarcube: Click the Add button to add a new format in Twine

If you're not on Linux, type the file path manually in this format:

file:///home/your-username/path/to/SugarCube-2/format.js

Using SugarCube

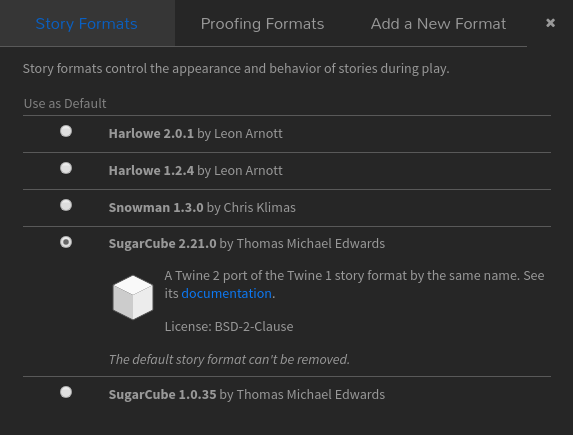

To switch a project to SugarCube, enter the storyboard mode of your project.

In the story board view, click the title of your storyboard in the lower-left corner of the Twine window and select Change Story Format.

In the Story format window that appears, select the SugarCube 2.x option.

Select SugarCube in the Story Format window

Images

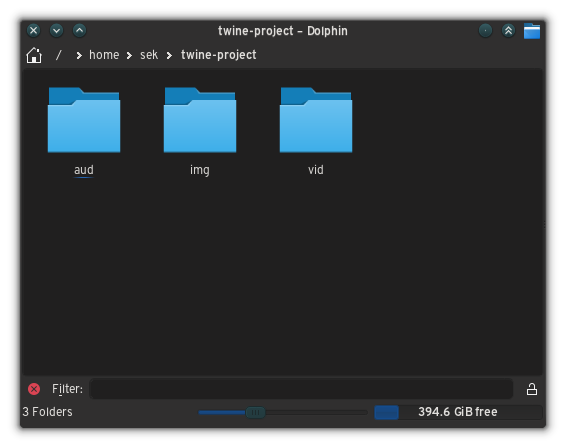

Before adding images, audio, or video to a Twine project, create a project directory in which to keep copies of your assets. This is vital, because these assets remain separate from the HTML file that Twine exports, so the final step of creating your story will be to take your exported HTML file and drop it in place alongside all the media it needs. If you're used to programming, video editing, or web design, this is a familiar discipline, but if you're new to this kind of content creation, you may not have encountered this before, so be especially diligent in organizing your assets.

Create a project directory somewhere. Inside this directory, create a subdirectory called img for your images, audio for your audio, video for video, and so on.

Create subdirectories for your project files in Twine

For this example, I use an image from openclipart.org. You can use this, or something similar. Regardless of what you use, place your image in your img directory.

Continuing with the hello_world project, you can add an image to one of the passages using SugarCube's image syntax:

<img src="https://opensource.com/img/earth.svg" alt="An image of the world." />

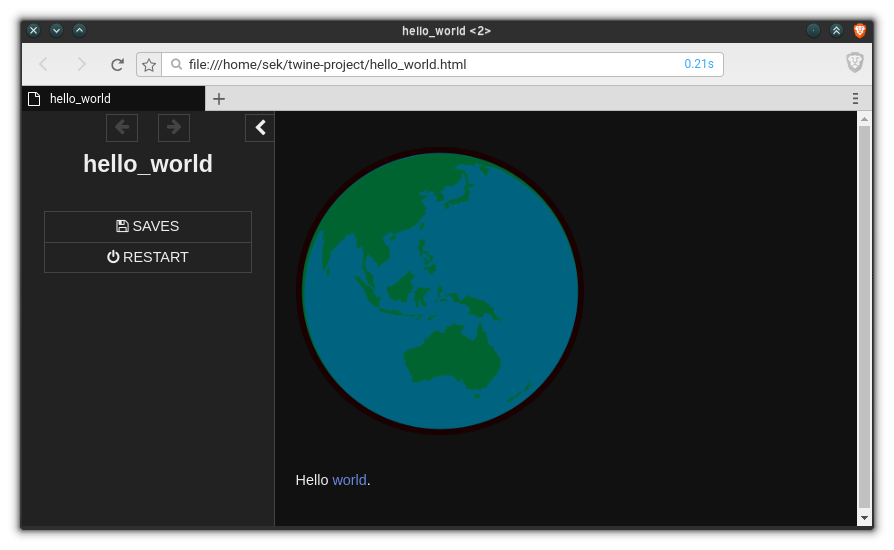

Hello [[world]].If you try to play your project after adding your images, you'll find that all the image links are broken. This is because Twine is located outside of your project directory. To test a multimedia Twine project, export it as a file and place the file in your project directory. Don't put it inside any of the subdirectories you created; simply place it in your project directory and open it in a web browser.

Previewing media files added to Twine project

Other media files function in basically the same way, utilizing HTML5 media tags to display the media and SugarCube macros to control when playback begins and ends.

Variables and programming

You can do a lot by leading a player to one passage or another depending on what choices they have made, but you can cut down on how many passages you need by using variables.

If you have never programmed before, take a moment to read through my introduction to programming concepts. The article uses Python, but all the same concepts apply to Twine and basically any other programming language you're likely to encounter.

For example, since the hello_world story is initially set on Earth, the next step in the story could be to offer a variety of trips to other worlds. Each time the reader returns to Earth, the game can display a tally of the worlds they have visited. This would be essentially impossible to do linearly, because you would never be able to tell which path a reader has taken in their exploration. For instance, one reader might visit Mars first, then Mercury. Another might never go to Mars at all, instead visiting Jupiter, Saturn, and then Mercury. You would have to make one passage for every possible combination, and that solution simply doesn't scale.

With variables, however, you can track a reader's progress and display messages accordingly.

To make this work, you must set a variable each time a reader reaches a new planet. In the game universe of the hello_world game, planets are actually open source projects, so each time a user visits a passage about an open source project, set a variable to "prove" that the reader has visited.

Variables in SugarCube syntax are set with the <<set>> macro. SugarCube has lots of macros, and they're all handy. This example project uses a few.

Change the second passage you created to provide the reader a few new options for exploration:

This was made in [[Twine]] on [[Linux]].

<<choice Start "Return to Earth.">>

You're using the <<choice>> macro here, which links any string of text straight back to a given passage. In this case, the <<choice>> macro links the string "Return to Earth" to the Start passage.

In the new passage, insert this text:

Twine is an interactive story framework. It runs on all operating systems, but I prefer to use it on [[Linux]].

<<set $twine to true>>

<<choice Start "Return to Earth.">>

In this code, you use the <<set>> macro to create a new variable called $twine. This variable is a Boolean, because you're just setting it to "true". You'll see why that's significant soon.

In the Linux passage, enter this text:

Linux is an open source [[Unix]]-like operating system.

<<set $linux to true>>

<<choice Start "Return to Earth.">>

And in the Unix passage:

BSD is an open source version of AT&T's Unix operating system.

<<set $bsd to true>>

<<choice Start "Return to Earth.">>

Now that the story has five passages for a reader to explore, it's time to use SugarCube to detect which variable has been set each time a reader returns to Earth.

To detect the state of a variable and generate HTML accordingly, use the <<if>> macro.

<img src="https://opensource.com/img/earth.png" alt="An image of the world." />

Hello [[world]].

<<nobr>>

<<ul>>

<<if $twine is true>><<li>>Planet Twine<</li>><</if>>

<<if $linux is true>><<li>>Planet Linux<</li>><</if>>

<<if $bsd is true>><<li>>Planet BSD<</li>><</if>>

<</ul>>

For testing purposes, you can press the Play button in the lower-right corner. You won't see your image, but look past that in the interest of testing.

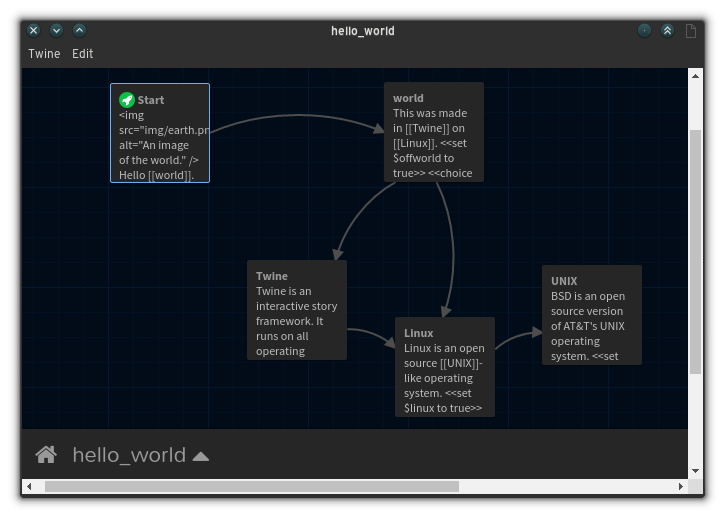

A more complex story board

Navigate through the story, returning to Earth periodically. Notice that a tally of each place you visited appears at the bottom of the Start passage each time you return.

There's nothing explaining why the list of places visited is appearing, though. Can you figure out how to explain the tally of explored passages to the reader?

You could just preface the tally list with an introductory sentence like "So far you have visited:" but when the user first arrives, the list will be empty so your introductory sentence will be introducing nothing.

A better way to manage it is with one more variable to indicate that the user has left Earth.

Change the world passage:

This was made in [[Twine]] on [[Linux]].

<<set $offworld to true>>

<<choice Start "Return to Earth.">>

Then use another <<if>> macro to detect whether or not the $offworld variable is set to true.

The way Twine parses wikitext sometimes results in more blank lines than you intend, so to compress the list of places visited, use the <<nobr>> macro to prevent line breaks.

<img src="https://opensource.com/img/earth.png" alt="An image of the world." />

Hello [[world]].

<<nobr>>

<<ul>>

<<if $twine is true>><<li>>Planet Twine<</li>><</if>>

<<if $linux is true>><<li>>Planet Linux<</li>><</if>>

<<if $bsd is true>><<li>>Planet BSD<</li>><</if>>

<</ul>>

<</nobr>> Try playing the story again. Notice that the reader isn't welcomed back to Earth until they have left Earth.

Explore everything

SugarCube is a powerful engine. Using it is often a question of knowing what's available rather than not having the ability to do something. Luckily, its documentation is very good, so refer to its macro list often.

You can make further modifications to your project by changing the CSS stylesheet. To do this, click the title of your project in story board mode and select Edit Story Stylesheet. If you're familiar with JavaScript, you can also script your stories with the Edit Story JavaScript.

There's no limit to what Twine can do as your interactive fiction engine. It can create text adventures, and it can serve as a prototype for more complex games, point-and-click RPGs, business presentations, late night talk show supplements, and just about anything else you can imagine. Explore the Twine wiki, take a look at other people's works on the Interactive Fiction Database, and then make your own.

2 Comments