How do you install an application on Linux? As with many operating systems, there isn't just one answer to that question. Applications can come from so many sources—it's nearly impossible to count—and each development team may deliver their software whatever way they feel is best. Knowing how to install what you're given is part of being a true power user of your OS.

Repositories

For well over a decade, Linux has used software repositories to distribute software. A "repository" in this context is a public server hosting installable software packages. A Linux distribution provides a command, and usually a graphical interface to that command, that pulls the software from the server and installs it onto your computer. It's such a simple concept that it has served as the model for all major cellphone operating systems and, more recently, the "app stores" of the two major closed source computer operating systems.

opensource.com

Installing from a software repository is the primary method of installing apps on Linux. It should be the first place you look for any application you intend to install.

To install from a software repository, there's usually a command:

$ sudo dnf install inkscape

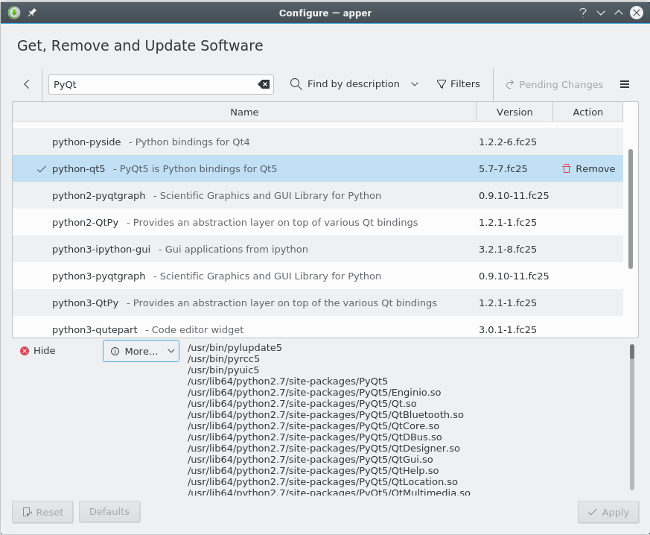

The actual command you use depends on what distribution of Linux you use. Fedora uses dnf, OpenSUSE uses zypper, Debian and Ubuntu use apt, Slackware uses sbopkg, FreeBSD uses pkg_add, and Illumos-based OpenIndiana uses pkg. Whatever you use, the incantation usually involves searching for the proper name of what you want to install, because sometimes what you call software is not its official or solitary designation:

$ sudo dnf search pyqt

PyQt.x86_64 : Python bindings for Qt3

PyQt4.x86_64 : Python bindings for Qt4

python-qt5.x86_64 : PyQt5 is Python bindings for Qt5

Once you have located the name of the package you want to install, use the install subcommand to perform the actual download and automated install:

$ sudo dnf install python-qt5

For specifics on installing from a software repository, see your distribution's documentation.

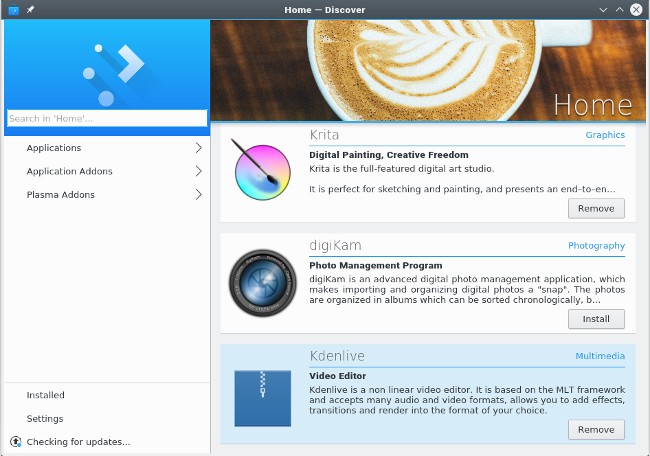

The same generally holds true with the graphical tools. Search for what you think you want, and then install it.

opensource.com

Like the underlying command, the name of the graphical installer depends on what distribution you are running. The relevant application is usually tagged with the software or package keywords, so search your launcher or menu for those terms, and you'll find what you need. Since open source is all about user choice, if you don't like the graphical user interface (GUI) that your distribution provides, there may be an alternative that you can install. And now you know how to do that.

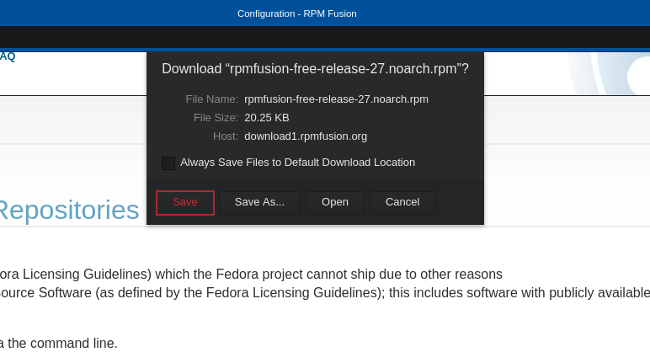

Extra repositories

Your distribution has its standard repository for software that it packages for you, and there are usually extra repositories common to your distribution. For example, EPEL serves Red Hat Enterprise Linux and CentOS, RPMFusion serves Fedora, Ubuntu has various levels of support as well as a Personal Package Archive (PPA) network, Packman provides extra software for OpenSUSE, and SlackBuilds.org provides community build scripts for Slackware.

By default, your Linux OS is set to look at just its official repositories, so if you want to use additional software collections, you must add extra repositories yourself. You can usually install a repository as though it were a software package. In fact, when you install certain software, such as GNU Ring video chat, the Vivaldi web browser, Google Chrome, and many others, what you are actually installing is access to their private repositories, from which the latest version of their application is installed to your machine.

opensource.com

You can also add the repository manually by editing a text file and adding it to your package manager's configuration directory, or by running a command to install the repository. As usual, the exact command you use depends on the distribution you are running; for example, here is a dnf command that adds a repository to the system:

$ sudo dnf config-manager --add-repo=https://example.com/pub/centos/7

Installing apps without repositories

The repository model is so popular because it provides a link between the user (you) and the developer. When important updates are released, your system kindly prompts you to accept the updates, and you can accept them all from one centralized location.

Sometimes, though, there are times when a package is made available with no repository attached. These installable packages come in several forms.

Linux packages

Sometimes, a developer distributes software in a common Linux packaging format, such as RPM, DEB, or the newer but very popular FlatPak or Snap formats. You make not get access to a repository with this download; you might just get the package.

The video editor Lightworks, for example, provides a .deb file for APT users and an .rpm file for RPM users. When you want to update, you return to the website and download the latest appropriate file.

These one-off packages can be installed with all the same tools used when installing from a repository. If you double-click the package you download, a graphical installer launches and steps you through the install process.

Alternately, you can install from a terminal. The difference here is that a lone package file you've downloaded from the internet isn't coming from a repository. It's a "local" install, meaning your package management software doesn't need to download it to install it. Most package managers handle this transparently:

$ sudo dnf install ~/Downloads/lwks-14.0.0-amd64.rpm

In some cases, you need to take additional steps to get the application to run, so carefully read the documentation about the software you're installing.

Generic install scripts

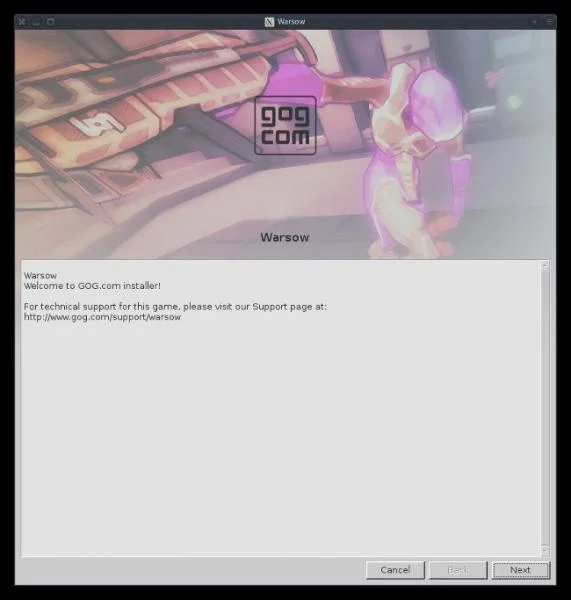

Some developers release their packages in one of several generic formats. Common extensions include .run and .sh. NVIDIA graphic card drivers, Foundry visual FX packages like Nuke and Mari, and many DRM-free games from GOG use this style of installer.

This model of installation relies on the developer to deliver an installation "wizard." Some of the installers are graphical, while others just run in a terminal.

There are two ways to run these types of installers.

- You can run the installer directly from a terminal:

$ sh ./game/gog_warsow_x.y.z.sh

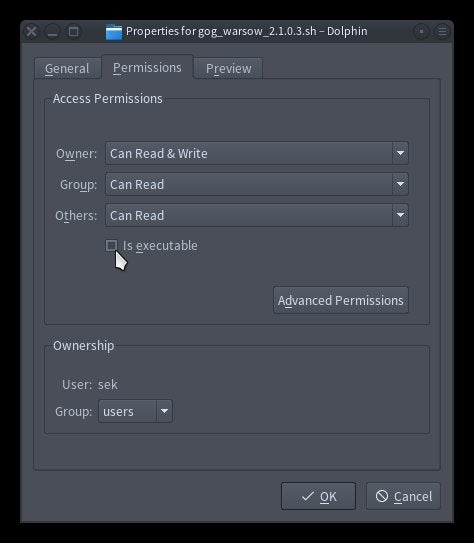

- Alternately, you can run it from your desktop by marking it as executable. To mark an installer executable, right-click on its icon and select Properties.

opensource.com

Once you've given permission for it to run, double-click the icon to start the install.

opensource.com

For the rest of the install, just follow the instructions on the screen.

AppImage portable apps

The AppImage format is relatively new to Linux, although its concept is based on both NeXT and Rox. The idea is simple: everything required to run an application is placed into one directory, and then that directory is treated as an "app." To run the application, you just double-click the icon, and it runs. There's no need or expectation that the application is installed in the traditional sense; it just runs from wherever you have it lying around on your hard drive.

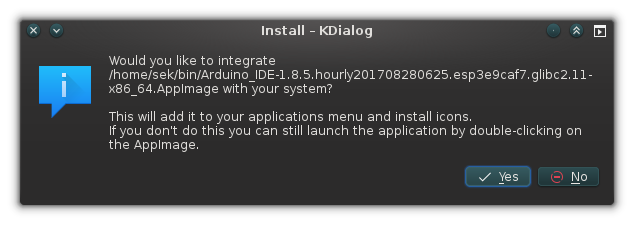

Despite its ability to run as a self-contained app, an AppImage usually offers to do some soft system integration.

opensource.com

If you accept this offer, a local .desktop file is installed to your home directory. A .desktop file is a small configuration file used by the Applications menu and mimetype system of a Linux desktop. Essentially, placing the desktop config file in your home directory's application list "installs" the application without actually installing it. You get all the benefits of having installed something, and the benefits of being able to run something locally, as a "portable app."

Application directory

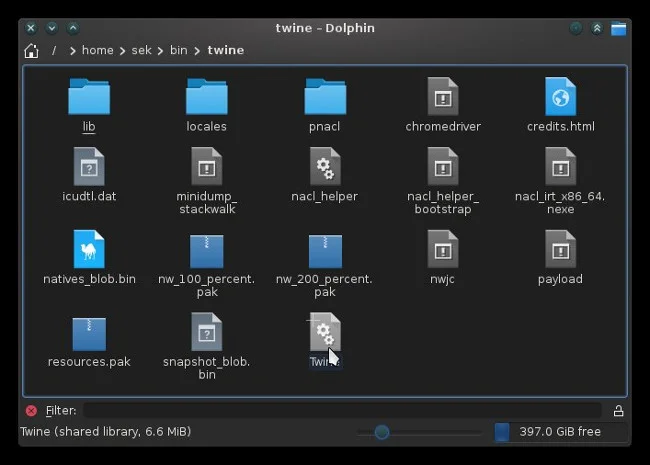

Sometimes, a developer just compiles an application and posts the result as a download, with no install script and no packaging. Usually, this means that you download a TAR file, extract it, and then double-click the executable file (it's usually the one with the name of the software you downloaded).

opensource.com

When presented with this style of software delivery, you can either leave it where you downloaded it and launch it manually when you need it, or you can do a quick and dirty install yourself. This involves two simple steps:

- Save the directory to a standard location and launch it manually when you need it.

- Save the directory to a standard location and create a

.desktopfile to integrate it into your system.

If you're just installing applications for yourself, it's traditional to keep a bin directory (short for "binary") in your home directory as a storage location for locally installed applications and scripts. If you have other users on your system who need access to the applications, it's traditional to place the binaries in /opt. Ultimately, it's up to you where you store the application.

Downloads often come in directories with versioned names, such as twine_2.13 or pcgen-v6.07.04. Since it's reasonable to assume you'll update the application at some point, it's a good idea to either remove the version number or to create a symlink to the directory. This way, the launcher that you create for the application can remain the same, even though you update the application itself.

To create a .desktop launcher file, open a text editor and create a file called twine.desktop. The Desktop Entry Specification is defined by FreeDesktop.org. Here is a simple launcher for a game development IDE called Twine, installed to the system-wide /opt directory:

[Desktop Entry]

Encoding=UTF-8

Name=Twine

GenericName=Twine

Comment=Twine

Exec=/opt/twine/Twine

Icon=/usr/share/icons/oxygen/64x64/categories/applications-games.png

Terminal=false

Type=Application

Categories=Development;IDE;

The tricky line is the Exec line. It must contain a valid command to start the application. Usually, it's just the full path to the thing you downloaded, but in some cases, it's something more complex. For example, a Java application might need to be launched as an argument to Java itself:

Exec=java -jar /path/to/foo.jar

Sometimes, a project includes a wrapper script that you can run so you don't have to figure out the right command:

Exec=/opt/foo/foo-launcher.sh

In the Twine example, there's no icon bundled with the download, so the example .desktop file assigns a generic gaming icon that shipped with the KDE desktop. You can use workarounds like that, but if you're more artistic, you can just create your own icon, or you can search the Internet for a good icon. As long as the Icon line points to a valid PNG or SVG file, your application will inherit the icon.

The example script also sets the application category primarily to Development, so in KDE, GNOME, and most other Application menus, Twine appears under the Development category.

To get this example to appear in an Application menu, place the twine.desktop file into one of two places:

- Place it in

~/.local/share/applicationsif you're storing the application in your own home directory. - Place it in

/usr/share/applicationsif you're storing the application in/optor another system-wide location and want it to appear in all your users' Application menus.

And now the application is installed as it needs to be and integrated with the rest of your system.

Compiling from source

Finally, there's the truly universal install format: source code. Compiling an application from source code is a great way to learn how applications are structured, how they interact with your system, and how they can be customized. It's by no means a push-button process, though. It requires a build environment, it usually involves installing dependency libraries and header files, and sometimes a little bit of debugging.

To learn more about compiling from source code, read my article on the topic.

Now you know

Some people think installing software is a magical process that only developers understand, or they think it "activates" an application, as if the binary executable file isn't valid until it has been "installed." Hopefully, learning about the many different methods of installing has shown you that install is really just shorthand for "copying files from one place to the appropriate places on your system." There's nothing mysterious about it. As long as you approach each install without expectations of how it's supposed to happen, and instead look for what the developer has set up as the install process, it's generally easy, even if it is different from what you're used to.

The important thing is that an installer is honest with you. If you come across an installer that attempts to install additional software without your consent (or maybe it asks for consent, but in a confusing or misleading way), or that attempts to run checks on your system for no apparent reason, then don't continue an install.

Good software is flexible, honest, and open. And now you know how to get good software onto your computer.

1 Comment