Hong Kong can be hot and humid, even at night, and many people use air conditioning to make their homes more bearable. When my oldest son was a baby, the air conditioning unit in his bedroom had manual controls and no thermostat functionality. It was either on or off, and allowing it to run continuously overnight caused the room to get cold and wasted energy and money.

I decided to fix this problem with an Internet of Things solution based on a Raspberry Pi. Later I took it a step further with a baby monitor add-on. In this article, I'll explain how I did it, and the code is available on my GitHub page.

Setting up the air conditioner controller

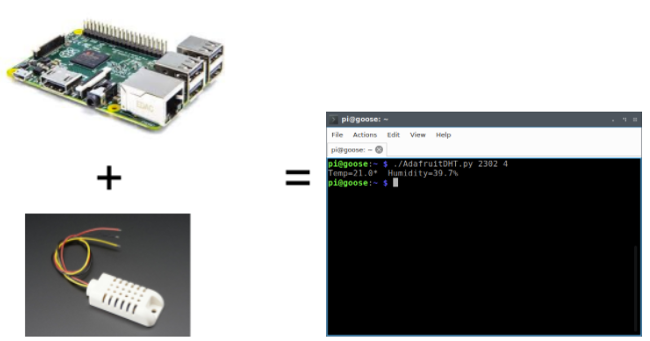

I solved the first part of my problem with an Orvibo S20 WiFi-connected smart plug and smartphone application. Although this allowed me to control the air conditioning unit remotely, it was still a manual process, and I wanted to try and automate it. I found a project on Instructables that seemed to match my requirements: It used a Raspberry Pi to measure local temperature and humidity readings from an AM2302 sensor and record them to a MySQL database.

Using crimp terminal contacts with crimp housings made it a pinch to connect the temperature/humidity sensor to the correct GPIO pins on the Raspberry Pi. Fortunately, the AM2302 sensor has open source software for taking readings, with helpful Python examples.

The software for interfacing with the AM2302 sensor has been updated since I put my project together, and the original code I used is now considered legacy and unmaintained. The code is made up of a small binary object to connect to the sensor and some Python scripts to interpret the readings and return the correct values.

opensource.com

With the sensor connected to the Raspberry Pi, the Python code can correctly return temperature and humidity readings. Connecting Python to a MySQL database is straightforward, and there are plenty of code examples that use the python-mysql bindings. Because I needed to monitor the temperature and humidity continuously, I wrote software to do this.

In fact, I ended up with two solutions, one that would run continuously as a process and periodically poll the sensor (typically at one-minute intervals), and another Python script that ran once and exited. I decided to use the run-once-and-exit approach coupled with cron to call this script every minute. The main reason was that the continuous (looped) script occasionally would not return a reading, which could lead to a buildup of processes trying to read the sensor, and that would eventually cause a system to hang due to lack of available resources.

I also found a convenient Perl script to programmatically control my smart plug. This was an essential piece of the jigsaw, as it meant I could trigger the Perl script if certain temperature and/or humidity conditions were met. After some testing, I decided to create a separate checking script that would pull the latest values from the MySQL database and set the smart plug on or off depending upon the values returned. Separating the logic to run the plug control script from the sensor-reading script also meant that it operated independently and would continue to run, even if the sensor-reading script developed problems.

It made sense to make the temperature at which the air conditioner would switch on/off configurable, so I moved these values to a configuration file that the control script read. I also found that, although the sensor was generally accurate, occasionally it would return incorrect readings. The sensor script was modified to not write temperature or humidity values to the MySQL database that were significantly different from the previous values. Likewise the allowed variance of temperature or humidity between consecutive readings was set in a general configuration file, and if the reading was outside these limits the values would not be committed to the database.

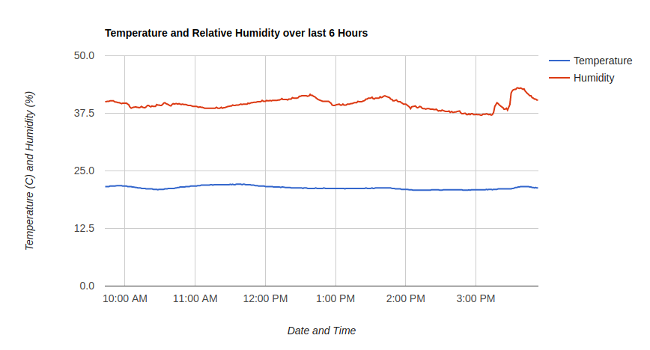

Although this seemed like quite a lot of effort to make a thermostat, recording the data to a MySQL database meant it was available for further analysis to identify usage patterns. There are many graphing options available to present data from a MySQL database, and I decided to use Google Chart to display the data on a web page.

opensource.com

Adding a baby monitor camera

The open nature of the Raspberry Pi meant I could continue to add functionality—and I had plenty of open GPIO pins available. My next idea was to add a camera module to set it up as a baby monitor, given that the device was already in the baby's bedroom.

I needed a camera that works in the dark, and the Pi Noir camera module is perfect for this. The Pi Noir is the same as the Raspberry Pi's regular camera module, except it doesn't have an infrared (IR) filter. This means daytime images may have a slightly purple tint, but it will display images lit with IR light in the dark.

Now I needed a source of IR light. Due to the Pi's popularity and low barrier of entry, there are a huge number of peripherals and add-ons for it. Of the many IR sources available, the one that caught my attention was the Bright Pi. It draws power from the Raspberry Pi and fits around the camera Pi module to provide a source of IR and normal light. The only drawback was I needed to dust off my rusty soldering skills.

It might have taken me longer than most, but my soldering skills were up to it, and I was able to successfully attach all the IR LEDs to the housing and connect the IR light source to the Pi's GPIO pins. This also meant that the Pi could programmatically control when the IR LEDs were lit, as well as their light intensity.

It also made sense to have the video capture exposed via a web stream so I could watch it from the web page with the temperature and humidity readings chart. After further research, I chose to use a streaming software that used M-JPEG captures. Exposing the JPG source via the web page also allowed me to connect camera viewer applications on my smartphone to view the camera output there, as well.

Putting on the finishing touches

No Raspberry Pi project is complete without selecting an appropriate case for the Pi and its various components. After a lot of searching and comparing, there was one clear winner: SmartPi's Lego-style case. The Lego compatibility allowed me to build mounts for the temperature/humidity sensor and camera. Here's the final outcome:

opensource.com

Since then, I've made other changes and updates to my setup:

- I upgraded from a Raspberry Pi 2 Model B to a Raspberry Pi 3, which meant I could do away with the USB WiFi module.

- I replaced the Orvibo S20 with a TP-Link HS110 smart plug.

- I also plugged the Pi into a smart plug so I can do remote reboots/resets.

- I migrated the MySQL database off the Raspberry Pi, and it now runs in a container on a NAS device.

- I added a flexible tripod to allow for the best camera angle.

- I recompiled the USB WiFi module to disable the onboard flashing LED, which was one of the main advantages to upgrading to a Raspberry Pi 3.

- I've since built another monitor for my second child.

- I bought a bespoke night camera for my third child … due to lack of time.

Want to learn more? All the code is available on my GitHub page.

Do you have a Raspberry Pi project to share? Send us your story idea.

Comments are closed.