In my previous series on test-driven development (TDD) and mutation testing, I demonstrated the benefits of relying on examples when building a solution. That begs the question: What does "relying on examples" mean?

In that series, I described one of my expectations when building a solution to determine whether it's daytime or nighttime. I provided an example of a specific hour of the day that I consider to fall in the daytime category. I created a DateTime variable named dayHour and gave it the specific value of August 8, 2019, 7 hours, 0 minutes, 0 seconds.

My logic (or way of reasoning) was: "When the system is notified that the time is exactly 7am on August 8, 2019, I expect that the system will perform the necessary calculations and return the value Daylight."

Armed with such a specific example, it was very easy to create a unit test (Given7amReturnDaylight). I then ran the tests and watched my unit test fail, which gave me the opportunity to work on fixing this early failure.

Iteration is the solution

One very important aspect of TDD (and, by proxy, of agile) is the fact that it is impossible to arrive at an acceptable solution unless you are iterating. TDD is a professional discipline based on the process of relentless iterating. It is very important to note that it mandates that each iteration must begin with a micro-failure. That micro-failure has only one purpose: to solicit immediate feedback. And that immediate feedback ensures we can rapidly close the gap between wanting a solution and getting a solution.

Iteration provides an opportunity to solicit immediate feedback by failing as early as possible. Because that failure is fast (i.e., it is a micro-failure), it is not alarming; even when we fail, we can remain calm, knowing that it will be easy to fix the failure. And the feedback from that failure will guide us toward fixing the failure.

Rinse, repeat, until we completely close the gap and deliver the solution that fully meets the expectation (but keep in mind that the expectation must also be a micro-expectation).

Why micro?

This approach often feels very unambitious. In TDD (and in agile), it's best to pick a tiny, almost trivial challenge, and then do the TDD song-and-dance by failing first, then iterating until we solve that trivial challenge. People who are used to more substantial, beefy engineering and problem solving tend to feel that such an exercise is beneath their level of competence.

One of the cornerstones of agile philosophy relies on reducing the problem space to multiple, smallest-possible surface areas. As Robert C. Martin puts it:

"Agile is a small idea about the small problems of small programming teams doing small things"

But how can making an unimpressive series of such pedestrian, minuscule, and almost insignificant micro-victories ever enable us to reach the big-scale solution?

Here is where sophisticated and elaborate systems thinking comes into play. When building a system, there's always the risk of ending up with a dreaded "monolith." A monolith is a system built on the principle of tight coupling. Any part of the monolith is highly dependent on many other parts of the same monolith. That arrangement makes the monolith very brittle, unreliable, and difficult to operate, maintain, troubleshoot, and fix.

The only way to avoid this trap is to minimize or, better yet, completely remove coupling. Instead of investing heroic efforts into building elaborate parts that will be assembled into a system, it is much better to take humble, baby steps toward building tiny, micro parts. These micro parts have very little capability on their own, and will, by virtue of such arrangement, not be dependent on other components. This will minimize and even remove any coupling.

The desired end game in building a useful, elaborate system is to compose it from a collection of generic, completely independent components. The more generic each component is, the more robust, resilient, and flexible the resulting system will be. Also, having a collection of generic components enables them to be repurposed to build brand new systems by reconfiguring those components.

Consider a toy castle made out of Lego blocks. If we pick almost any block from that castle and examine it in isolation, we won't be able to find anything on that block that specifies it is a Lego block meant for building a castle. The block itself is sufficiently generic, which makes it suitable for building other contraptions, such as toy cars, toy airplanes, toy boats, etc. That's the power of having generic components.

TDD is a proven discipline for delivering generic, independent, and autonomous components that can be safely used to assemble large, sophisticated systems expediently. As in agile, TDD is focused on micro-activities. And because agile is based on the fundamental principle known as "the Whole Team," the humble approach illustrated here is also important when specifying business examples. If the example used for building a component is not modest, it will be difficult to meet the expectations. Therefore, the expectations must be humble, which makes the resulting examples equally humble.

For instance, if a member of the Whole Team (a requester) provides the developer with an expectation and an example that reads:

"When processing an order, make sure to apply appropriate discount for orders made by loyal customers, or for orders over certain monetary value, or both."

The developer should recognize that this example is too ambitious. That's not a humble expectation. It is not sufficiently micro, if you will. The developer should always strive to guide a requester in being more specific and micro-level when crafting examples. Paradoxically, the more specific the example, the more generic the resulting solution will be.

A much better, more effective expectation and example would be:

"Discount made for an order greater than $100.00 is $18.00."

Or:

"Discount made for an order greater than $100.00 that was made by a customer who already placed three orders is $25.00."

Such micro-examples make it easy to turn them into automated micro-expectations (read: unit tests). Such expectations will make us fail, and then we will pick ourselves up and iterate until we deliver the solution—a robust, generic component that knows how to calculate discounts based on the micro-examples supplied by the Whole Team.

Writing quality unit tests

Merely writing unit tests without any concern about their quality is a fool's errand. Shoddily written unit tests will result in bloated, tightly coupled code. Such code is brittle, difficult to reason about, and often nearly impossible to fix.

We need to lay down some ground rules for writing quality unit tests. These ground rules will help us make swift progress in building robust, reliable solutions. The easiest way to do that is to introduce a mnemonic in the form of an acronym: FIRST, which says unit tests must be:

- F = Fast

- I = Independent

- R = Repeatable

- S = Self-validating

- T = Thorough

Fast

Since a unit test describes a micro-example, it should expect very simple processing from the implemented code. This means that each unit test should be very fast to run.

Independent

Since a unit test describes a micro-example, it should describe a very simple process that does not depend on any other unit test.

Repeatable

Since a unit test does not depend on any other unit test, it must be fully repeatable. What that means is that each time a certain unit test runs, it produces the same results as the previous time it ran. Neither the number of times the unit tests run nor the order in which they run should ever affect the expected output.

Self-validating

When unit tests run, the outcome of the testing should be instantly visible. Developers should not be expected to reach for some other source(s) of information to find out whether their unit tests failed or passed.

Thorough

Unit tests should describe all the expectations as defined in the micro-examples.

Well-structured unit tests

Unit tests are code. And the same as any other code, unit tests need to be well-structured. It is unacceptable to deliver sloppy, messy unit tests. All the principles that apply to the rules governing clean implementation code apply with equal force to unit tests.

A time-tested and proven methodology for writing reliable quality code is based on the clean code principle known as SOLID. This acronym that helps us remember five very important principles:

- S = Single responsibility principle

- O = Open–closed principle

- L = Liskov substitution principle

- I = Interface segregation principle

- D = Dependency inversion principle

Single responsibility principle

Each component must be responsible for performing only one operation. This principle is illustrated in this meme

Pumping septic tanks is an operation that must be kept separate from filling swimming pools.

Applied to unit tests, this principle ensures that each unit test verifies one—and only one—expectation. From a technical standpoint, this means each unit test must have one and only one Assert statement.

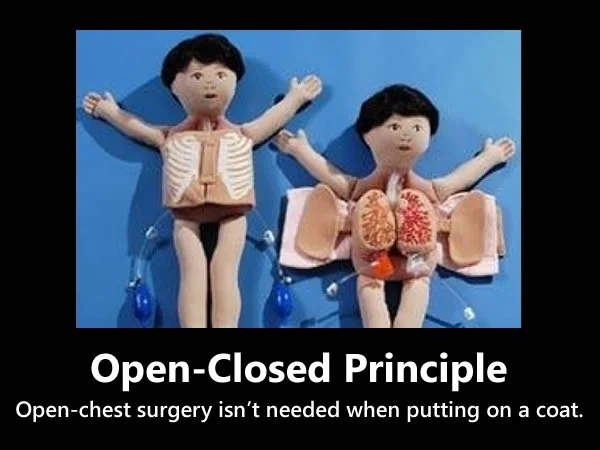

Open–closed principle

This principle states that a component should be open for extensions, but closed for any modifications.

Applied to unit tests, this principle ensures that we will not implement a change to an existing unit test in that unit test. Instead, we must write a brand new unit test that will implement the changes.

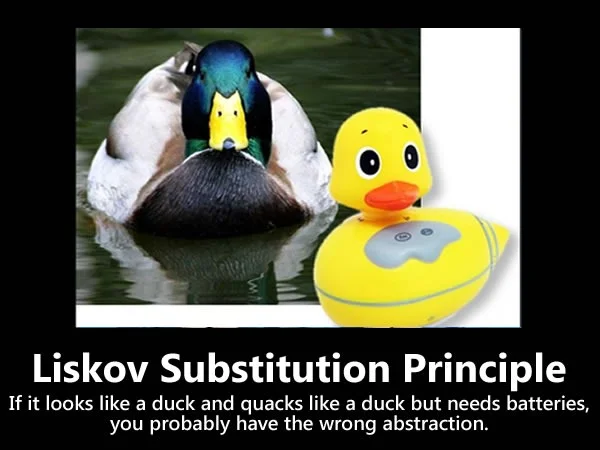

Liskov substitution principle

This principle provides a guide for deciding which level of abstraction may be appropriate for the solution.

Applied to unit tests, this principle guides us to avoid tight coupling with dependencies that depend on the underlying computing environment (such as databases, disks, network, etc.).

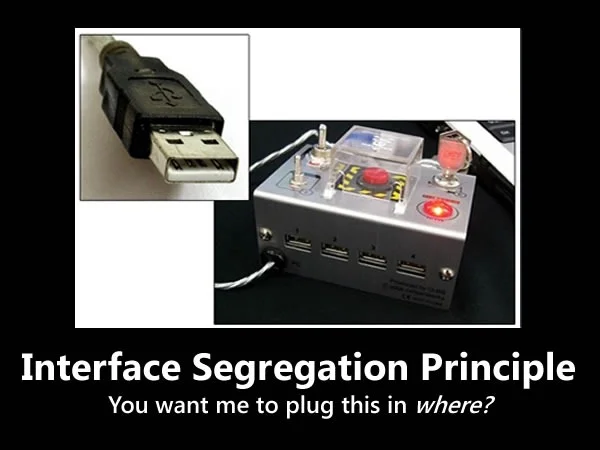

Interface segregation principle

This principle reminds us not to bloat APIs. When subsystems need to collaborate to complete a task, they should communicate via interfaces. But those interfaces must not be bloated. If a new capability becomes necessary, don't add it to the already defined interface; instead, craft a brand new interface.

Applied to unit tests, removing the bloat from interfaces helps us craft more specific unit tests, which, in turn, results in more generic components.

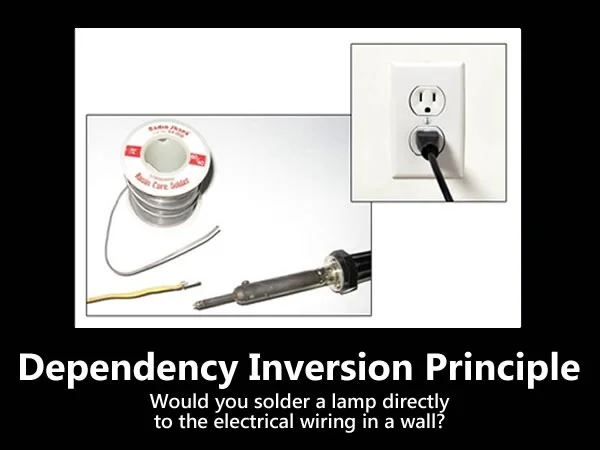

Dependency inversion principle

This principle states that we should control our dependencies, instead of dependencies controlling us. If there is a need to use another component's services, instead of being responsible for instantiating that component within the component we are building, it must instead be injected into our component.

Applied to the unit tests, this principle helps separate the intention from the implementation. We must strive to inject only those dependencies that have been sufficiently abstracted. That approach is important for ensuring unit tests are not mixed with integration tests.

Testing the tests

Finally, even if we manage to produce well-structured unit tests that fulfill the FIRST principles, it does not guarantee that we have delivered a solid solution. TDD best practices rely on the proper sequence of events when building components/services; we are always and invariably expected to provide a description of our expectations (supplied in the micro-examples). Only after those expectations are described in the unit test can we move on to writing the implementation code. However, two unwanted side effects can, and often do, happen while writing implementation code:

- Implemented code enables the unit tests to pass, but they are written in a convoluted way, using unnecessarily complex logic

- Implemented code gets tagged on AFTER the unit tests have been written

In the first case, even if all unit tests pass, mutation testing uncovers that some mutants have survived. As I explained in Mutation testing by example: Evolving from fragile TDD, that is an extremely undesirable situation because it means that the solution is unnecessarily complex and, therefore, unmaintainable.

In the second case, all unit tests are guaranteed to pass, but a potentially large portion of the codebase consists of implemented code that hasn't been described anywhere. This means we are dealing with mysterious code. In the best-case scenario, we could treat that mysterious code as deadwood and safely remove it. But more likely than not, removing this not-described, implemented code will cause some serious breakages. And such breakages indicate that our solution is not well engineered.

Conclusion

TDD best practices stem from the time-tested methodology called extreme programming (XP for short). One of the cornerstones of XP is based on the three C's:

- Card: A small card briefly specifies the intent (e.g., "Review customer request").

- Conversation: The card becomes a ticket to conversation. The whole team gets together and talks about "Review customer request." What does that mean? Do we have enough information/knowledge to ship the "review customer request" functionality in this increment? If not, how do we further slice this card?

- Concrete confirmation examples: This includes all the specific values plugged in (e.g., concrete names, numeric values, specific dates, whatever else is pertinent to the use case) plus all values expected as an output of the processing.

Starting from such micro-examples, we write unit tests. We watch unit tests fail, then make them pass. And while doing that, we observe and respect the best software engineering practices: the FIRST principles, the SOLID principles, and the mutation testing discipline (i.e., kill all surviving mutants).

This ensures that our components and services are delivered with solid quality built in. And what is the measure of that quality? Simple—the cost of change. If the delivered code is costly to change, it is of shoddy quality. Very high-quality code is structured so well that it is simple and inexpensive to change and, at the same time, does not incur any change-management risks.

3 Comments