This is part 11 in an ongoing series about creating video games in Python 3 using the Pygame module. Previous articles are:

- Learn how to program in Python by building a simple dice game

- Build a game framework with Python using the Pygame module

- How to add a player to your Python game

- Using Pygame to move your game character around

- What's a hero without a villain? How to add one to your Python game

- Add platforms to your game

- Simulate gravity in your Python game

- Add jumping to your Python platformer game

- Enable your Python game player to run forward and backward

- Using Python to set up loot in Pygame

If you've followed along with this series, you've learned all the essential syntax and patterns you need to create a video game with Python. However, it still lacks one vital component. This component isn't important just for programming games in Python; it's something you must master no matter what branch of computing you explore: Learning new tricks as a programmer by reading a language's or library's documentation.

Luckily, the fact that you're reading this article is a sign that you're comfortable with documentation. For the practical purpose of making your platform game more polished, in this article, you will add a score and health display to your game screen. But the not-so-secret agenda of this lesson is to teach you how to find out what a library offers and how you can use new features.

Displaying the score in Pygame

Now that you have loot that your player can collect, there's every reason to keep score so that your player sees just how much loot they've collected. You can also track the player's health so that when they hit one of the enemies, it has a consequence.

You already have variables that track score and health, but it all happens in the background. This article teaches you to display these statistics in a font of your choice on the game screen during gameplay.

Read the docs

Most Python modules have documentation, and even those that do not can be minimally documented by Python's Help function. Pygame's main page links to its documentation. However, Pygame is a big module with a lot of documentation, and its docs aren't exactly written in the same approachable (and friendly and elucidating and helpful) narrative style as articles on Opensource.com. They're technical documents, and they list each class and function available in the module, what kind of inputs each expects, and so on. If you're not comfortable referring to descriptions of code components, this can be overwhelming.

The first thing to do, before bothering with a library's documentation, is to think about what you are trying to achieve. In this case, you want to display the player's score and health on the screen.

Once you've determined your desired outcome, think about what components are required for it. You can think of this in terms of variables and functions or, if that doesn't come naturally to you yet, you can think generically. You probably recognize that displaying a score requires some text, which you want Pygame to draw on the screen. If you think it through, you might realize that it's not very different from rendering a player or loot or a platform on screen.

Technically, you could use graphics of numbers and have Pygame display those. It's not the easiest way to achieve your goal, but if it's the only way you know, then it's a valid way. However, if you refer to Pygame's docs, you see that one of the modules listed is font, which is Pygame's method for making printing text on the screen as easy as typing.

Deciphering technical documentation

The font documentation page starts with pygame.font.init(), which it lists as the function that is used to initialize the font module. It's called automatically by pygame.init(), which you already call in your code. Once again, you've reached a point that that's technically good enough. While you don't know how yet, you know that you can use the pygame.font functions to print text on the screen.

If you read further, however, you find that there's yet an even better way to print fonts. The pygame.freetype module is described in the docs this way:

The pygame.freetype module is a replacement for pygame.fontpygame module for loading and rendering fonts. It has all of the functionality of the original, plus many new features.

Further down the pygame.freetype documentation page, there's some sample code:

import pygame

import pygame.freetypeYour code already imports Pygame, but modify your import statements to include the Freetype module:

import pygame

import sys

import os

import pygame.freetypeUsing a font in Pygame

From the description of the font modules, it's clear that Pygame uses a font, whether it's one you provide or a default font built into Pygame, to render text on the screen. Scroll through the pygame.freetype documentation to find the pygame.freetype.Font function:

pygame.freetype.Font

Create a new Font instance from a supported font file.

Font(file, size=0, font_index=0, resolution=0, ucs4=False) -> Font

pygame.freetype.Font.name

Proper font name.

pygame.freetype.Font.path

Font file path

pygame.freetype.Font.size

The default point size used in renderingThis describes how to construct a font "object" in Pygame. It may not feel natural to you to think of a simple object onscreen as the combination of several code attributes, but it's very similar to how you built your hero and enemy sprites. Instead of an image file, you need a font file. Once you have a font file, you can create a font object in your code with the pygame.freetype.Font function and then use that object to render text on the screen.

Asset management

Because not everyone in the world has the exact same fonts on their computers, it's important to bundle your chosen font with your game. To bundle a font, first create a new directory in your game folder, right along with the directory you created for your images. Call it fonts.

Even though several fonts come with your computer, it's not legal to give those fonts away. It seems strange, but that's how the law works. If you want to ship a font with your game, you must find an open source or Creative Commons font that permits you to give the font away along with your game.

Sites that specialize in free and legal fonts include:

When you find a font that you like, download it. Extract the ZIP or TAR file and move the .ttf or .otf file into the fonts folder in your game project directory.

You aren't installing the font on your computer. You're just placing it in your game's fonts folder so that Pygame can use it. You can install the font on your computer if you want, but it's not necessary. The important thing is to have it in your game directory, so Pygame can "trace" it onto the screen.

If the font file has a complicated name with spaces or special characters, just rename it. The filename is completely arbitrary, and the simpler it is, the easier it is for you to type into your code.

Using a font in Pygame

Now tell Pygame about your font. From the documentation, you know that you'll get a font object in return when you provide at least the path to a font file to pygame.freetype.Font (the docs state explicitly that all remaining attributes are optional):

Font(file, size=0, font_index=0, resolution=0, ucs4=False) -> FontCreate a new variable called myfont to serve as your font in the game, and place the results of the Font function into that variable. This example uses the amazdoom.ttf font, but you can use whatever font you want. Place this code in your Setup section:

font_path = os.path.join(os.path.dirname(os.path.realpath(__file__)),"fonts","amazdoom.ttf")

font_size = tx

pygame.freetype.init()

myfont = pygame.freetype.Font(font_path, font_size)Displaying text in Pygame

Now that you've created a font object, you need a function to draw the text you want onto the screen. This is the same principle you used to draw the background and platforms in your game.

First, create a function, and use the myfont object to create some text, setting the color to some RGB value. This must be a global function; it does not belong to any specific class. Place it in the objects section of your code, but keep it as a stand-alone function:

def stats(score,health):

myfont.render_to(world, (4, 4), "Score:"+str(score), BLACK, None, size=64)

myfont.render_to(world, (4, 72), "Health:"+str(health), BLACK, None, size=64)Of course, you know by now that nothing happens in your game if it's not in the Main loop, so add a call to your stats function near the bottom of the file:

stats(player.score,player.health) # draw textTry your game. If you've been following the sample code in this article exactly, you'll get an error when you try to launch the game now.

Interpreting errors

Errors are important to programmers. When something fails in your code, one of the best ways to understand why is by reading the error output. Unfortunately, Python doesn't communicate the same way a human does. While it does have relatively friendly errors, you still have to interpret what you're seeing.

In this case, launching the game produces this output:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/home/tux/PycharmProjects/game_001/main.py", line 41, in <module>

font_size = tx

NameError: name 'tx' is not definedPython is aserting that the variable tx is not defined. You know this isn't true, because you've used tx in several places by now and it's worked as expected.

But Python also cites a line number. This is the line that caused Python to stop executing the code. It is not necessarily the line containing the error.

Armed with this knowledge, you can look at your code in an attempt to understand what has failed.

Line 41 attempts to set the font size to the value of tx. However, reading through the file in reverse, up from line 41, you might notice that tx (and ty) are not listed. In fact, tx and ty were placed haphazardly in your setup section because, at the time, it seemed easy and logical to place them along with other important tile information.

Moving the tx and ty lines from your setup section to some line above line 41 fixes the error.

When you entcounter errors in Python, take note of the hints it provides, and then read your source code carefully. It can take time to find an error, even for experienced programmers, but the better you understand Python the easier it becomes.

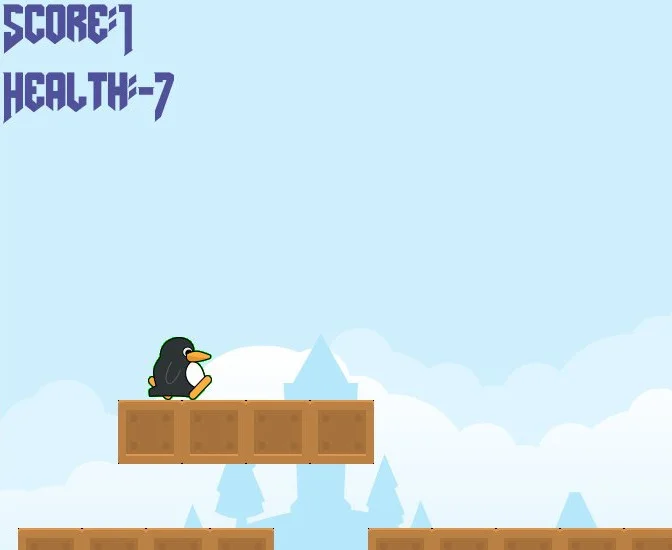

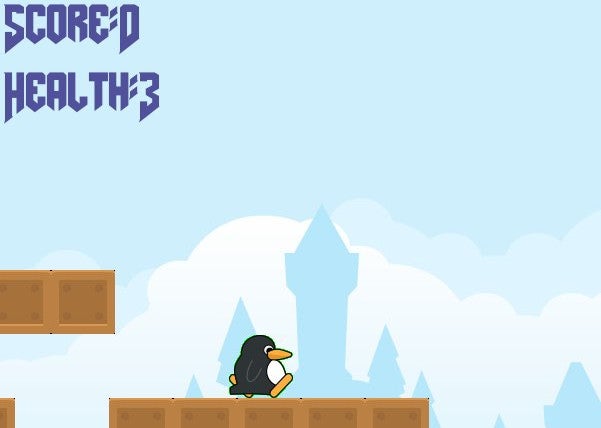

Running the game

When the player collects loot, the score goes up. When the player gets hit by an enemy, health goes down. Success!

There is one problem, though. When a player gets hit by an enemy, health goes way down, and that's not fair. You have just discovered a non-fatal bug. Non-fatal bugs are those little problems in applications that don't keep the application from starting up or even from working (mostly), but they either don't make sense, or they annoy the user. Here's how to fix this one.

Fixing the health counter

The problem with the current health point system is that health is subtracted for every tick of the Pygame clock that the enemy is touching the player. That means that a slow-moving enemy can take a player down to –200 health in just one encounter, and that's not fair. You could, of course, just give your player a starting health score of 10,000 and not worry about it; that would work, and possibly no one would mind. But there is a better way.

Currently, your code detects when a player and an enemy collide. The fix for the health-point problem is to detect two separate events: when the player and enemy collide and, once they have collided, when they stop colliding.

First, in your Player class, create a variable to represent when a player and enemy have collided:

self.frame = 0

self.health = 10

self.damage = 0In the update function of your Player class, remove this block of code:

for enemy in enemy_hit_list:

self.health -= 1

#print(self.health)And in its place, check for collision as long as the player is not currently being hit:

if self.damage == 0:

for enemy in enemy_hit_list:

if not self.rect.contains(enemy):

self.damage = self.rect.colliderect(enemy)You might see similarities between the block you deleted and the one you just added. They're both doing the same job, but the new code is more complex. Most importantly, the new code runs only if the player is not currently being hit. That means that this code runs once when a player and enemy collide and not constantly for as long as the collision happens, the way it used to.

The new code uses two new Pygame functions. The self.rect.contains function checks to see if an enemy is currently within the player's bounding box, and self.rect.colliderect sets your new self.damage variable to one when it is true, no matter how many times it is true.

Now even three seconds of getting hit by an enemy still looks like one hit to Pygame.

I discovered these functions by reading through Pygame's documentation. You don't have to read all the docs at once, and you don't have to read every word of each function. However, it's important to spend time with the documentation of a new library or module that you're using; otherwise, you run a high risk of reinventing the wheel. Don't spend an afternoon trying to hack together a solution to something that's already been solved by the framework you're using. Read the docs, find the functions, and benefit from the work of others!

Finally, add another block of code to detect when the player and the enemy are no longer touching. Then and only then, subtract one point of health from the player.

if self.damage == 1:

idx = self.rect.collidelist(enemy_hit_list)

if idx == -1:

self.damage = 0 # set damage back to 0

self.health -= 1 # subtract 1 hpNotice that this new code gets triggered only when the player has been hit. That means this code doesn't run while your player is running around your game world exploring or collecting loot. It only runs when the self.damage variable gets activated.

When the code runs, it uses self.rect.collidelist to see whether or not the player is still touching an enemy in your enemy list (collidelist returns negative one when it detects no collision). Once it is not touching an enemy, it's time to pay the self.damage debt: deactivate the self.damage variable by setting it back to zero and subtract one point of health.

Try your game now.

Now that you have a way for your player to know their score and health, you can make certain events occur when your player reaches certain milestones. For instance, maybe there's a special loot item that restores some health points. And maybe a player who reaches zero health points has to start back at the beginning of a level.

You can check for these events in your code and manipulate your game world accordingly.

Level up

You already know how to do so much. Now it's time to level up your skills. Go skim the documentation for new tricks and try them out on your own. Programming is a skill you develop, so don't stop with this project. Invent another game, or a useful application, or just use Python to experiment around with crazy ideas. The more you use it, the more comfortable you get with it, and eventually it'll be second nature.

Keep it going, and keep it open!

Here's all the code so far:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# by Seth Kenlon

# GPLv3

# This program is free software: you can redistribute it and/or

# modify it under the terms of the GNU General Public License as

# published by the Free Software Foundation, either version 3 of the

# License, or (at your option) any later version.

#

# This program is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but

# WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of

# MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. See the GNU

# General Public License for more details.

#

# You should have received a copy of the GNU General Public License

# along with this program. If not, see <https://www.gnu.org/licenses/>.

import pygame

import pygame.freetype

import sys

import os

'''

Variables

'''

worldx = 960

worldy = 720

fps = 40

ani = 4

world = pygame.display.set_mode([worldx, worldy])

forwardx = 600

backwardx = 120

BLUE = (80, 80, 155)

BLACK = (23, 23, 23)

WHITE = (254, 254, 254)

ALPHA = (0, 255, 0)

tx = 64

ty = 64

font_path = os.path.join(os.path.dirname(os.path.realpath(__file__)), "fonts", "amazdoom.ttf")

font_size = tx

pygame.freetype.init()

myfont = pygame.freetype.Font(font_path, font_size)

'''

Objects

'''

def stats(score,health):

myfont.render_to(world, (4, 4), "Score:"+str(score), BLUE, None, size=64)

myfont.render_to(world, (4, 72), "Health:"+str(health), BLUE, None, size=64)

# x location, y location, img width, img height, img file

class Platform(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

def __init__(self, xloc, yloc, imgw, imgh, img):

pygame.sprite.Sprite.__init__(self)

self.image = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images', img)).convert()

self.image.convert_alpha()

self.image.set_colorkey(ALPHA)

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

self.rect.y = yloc

self.rect.x = xloc

class Player(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

"""

Spawn a player

"""

def __init__(self):

pygame.sprite.Sprite.__init__(self)

self.movex = 0

self.movey = 0

self.frame = 0

self.health = 10

self.damage = 0

self.score = 0

self.is_jumping = True

self.is_falling = True

self.images = []

for i in range(1, 5):

img = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images', 'hero' + str(i) + '.png')).convert()

img.convert_alpha()

img.set_colorkey(ALPHA)

self.images.append(img)

self.image = self.images[0]

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

def gravity(self):

if self.is_jumping:

self.movey += 3.2

def control(self, x, y):

"""

control player movement

"""

self.movex += x

def jump(self):

if self.is_jumping is False:

self.is_falling = False

self.is_jumping = True

def update(self):

"""

Update sprite position

"""

# moving left

if self.movex < 0:

self.is_jumping = True

self.frame += 1

if self.frame > 3 * ani:

self.frame = 0

self.image = pygame.transform.flip(self.images[self.frame // ani], True, False)

# moving right

if self.movex > 0:

self.is_jumping = True

self.frame += 1

if self.frame > 3 * ani:

self.frame = 0

self.image = self.images[self.frame // ani]

# collisions

enemy_hit_list = pygame.sprite.spritecollide(self, enemy_list, False)

if self.damage == 0:

for enemy in enemy_hit_list:

if not self.rect.contains(enemy):

self.damage = self.rect.colliderect(enemy)

if self.damage == 1:

idx = self.rect.collidelist(enemy_hit_list)

if idx == -1:

self.damage = 0 # set damage back to 0

self.health -= 1 # subtract 1 hp

ground_hit_list = pygame.sprite.spritecollide(self, ground_list, False)

for g in ground_hit_list:

self.movey = 0

self.rect.bottom = g.rect.top

self.is_jumping = False # stop jumping

# fall off the world

if self.rect.y > worldy:

self.health -=1

print(self.health)

self.rect.x = tx

self.rect.y = ty

plat_hit_list = pygame.sprite.spritecollide(self, plat_list, False)

for p in plat_hit_list:

self.is_jumping = False # stop jumping

self.movey = 0

if self.rect.bottom <= p.rect.bottom:

self.rect.bottom = p.rect.top

else:

self.movey += 3.2

if self.is_jumping and self.is_falling is False:

self.is_falling = True

self.movey -= 33 # how high to jump

loot_hit_list = pygame.sprite.spritecollide(self, loot_list, False)

for loot in loot_hit_list:

loot_list.remove(loot)

self.score += 1

print(self.score)

plat_hit_list = pygame.sprite.spritecollide(self, plat_list, False)

self.rect.x += self.movex

self.rect.y += self.movey

class Enemy(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

"""

Spawn an enemy

"""

def __init__(self, x, y, img):

pygame.sprite.Sprite.__init__(self)

self.image = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images', img))

self.image.convert_alpha()

self.image.set_colorkey(ALPHA)

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

self.rect.x = x

self.rect.y = y

self.counter = 0

def move(self):

"""

enemy movement

"""

distance = 80

speed = 8

if self.counter >= 0 and self.counter <= distance:

self.rect.x += speed

elif self.counter >= distance and self.counter <= distance * 2:

self.rect.x -= speed

else:

self.counter = 0

self.counter += 1

class Level:

def ground(lvl, gloc, tx, ty):

ground_list = pygame.sprite.Group()

i = 0

if lvl == 1:

while i < len(gloc):

ground = Platform(gloc[i], worldy - ty, tx, ty, 'tile-ground.png')

ground_list.add(ground)

i = i + 1

if lvl == 2:

print("Level " + str(lvl))

return ground_list

def bad(lvl, eloc):

if lvl == 1:

enemy = Enemy(eloc[0], eloc[1], 'enemy.png')

enemy_list = pygame.sprite.Group()

enemy_list.add(enemy)

if lvl == 2:

print("Level " + str(lvl))

return enemy_list

# x location, y location, img width, img height, img file

def platform(lvl, tx, ty):

plat_list = pygame.sprite.Group()

ploc = []

i = 0

if lvl == 1:

ploc.append((200, worldy - ty - 128, 3))

ploc.append((300, worldy - ty - 256, 3))

ploc.append((550, worldy - ty - 128, 4))

while i < len(ploc):

j = 0

while j <= ploc[i][2]:

plat = Platform((ploc[i][0] + (j * tx)), ploc[i][1], tx, ty, 'tile.png')

plat_list.add(plat)

j = j + 1

print('run' + str(i) + str(ploc[i]))

i = i + 1

if lvl == 2:

print("Level " + str(lvl))

return plat_list

def loot(lvl):

if lvl == 1:

loot_list = pygame.sprite.Group()

loot = Platform(tx*5, ty*5, tx, ty, 'loot_1.png')

loot_list.add(loot)

if lvl == 2:

print(lvl)

return loot_list

'''

Setup

'''

backdrop = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images', 'stage.png'))

clock = pygame.time.Clock()

pygame.init()

backdropbox = world.get_rect()

main = True

player = Player() # spawn player

player.rect.x = 0 # go to x

player.rect.y = 30 # go to y

player_list = pygame.sprite.Group()

player_list.add(player)

steps = 10

eloc = []

eloc = [300, worldy-ty-80]

enemy_list = Level.bad(1, eloc)

gloc = []

i = 0

while i <= (worldx / tx) + tx:

gloc.append(i * tx)

i = i + 1

ground_list = Level.ground(1, gloc, tx, ty)

plat_list = Level.platform(1, tx, ty)

enemy_list = Level.bad( 1, eloc )

loot_list = Level.loot(1)

'''

Main Loop

'''

while main:

for event in pygame.event.get():

if event.type == pygame.QUIT:

pygame.quit()

try:

sys.exit()

finally:

main = False

if event.type == pygame.KEYDOWN:

if event.key == ord('q'):

pygame.quit()

try:

sys.exit()

finally:

main = False

if event.key == pygame.K_LEFT or event.key == ord('a'):

player.control(-steps, 0)

if event.key == pygame.K_RIGHT or event.key == ord('d'):

player.control(steps, 0)

if event.key == pygame.K_UP or event.key == ord('w'):

player.jump()

if event.type == pygame.KEYUP:

if event.key == pygame.K_LEFT or event.key == ord('a'):

player.control(steps, 0)

if event.key == pygame.K_RIGHT or event.key == ord('d'):

player.control(-steps, 0)

# scroll the world forward

if player.rect.x >= forwardx:

scroll = player.rect.x - forwardx

player.rect.x = forwardx

for p in plat_list:

p.rect.x -= scroll

for e in enemy_list:

e.rect.x -= scroll

for l in loot_list:

l.rect.x -= scroll

# scroll the world backward

if player.rect.x <= backwardx:

scroll = backwardx - player.rect.x

player.rect.x = backwardx

for p in plat_list:

p.rect.x += scroll

for e in enemy_list:

e.rect.x += scroll

for l in loot_list:

l.rect.x += scroll

world.blit(backdrop, backdropbox)

player.update()

player.gravity()

player_list.draw(world)

enemy_list.draw(world)

loot_list.draw(world)

ground_list.draw(world)

plat_list.draw(world)

for e in enemy_list:

e.move()

stats(player.score, player.health)

pygame.display.flip()

clock.tick(fps)

5 Comments