Cloud-init is a widely utilized industry-standard method for initializing cloud instances. Cloud providers use Cloud-init to customize instances with network configuration, instance information, and even user-provided configuration directives. It is also a great tool to use in your "private cloud at home" to add a little automation to the initial setup and configuration of your homelab's virtual and physical machines—and to learn more about how large cloud providers work. For a bit more detail and background, see my previous article on Cloud-init and why it is useful.

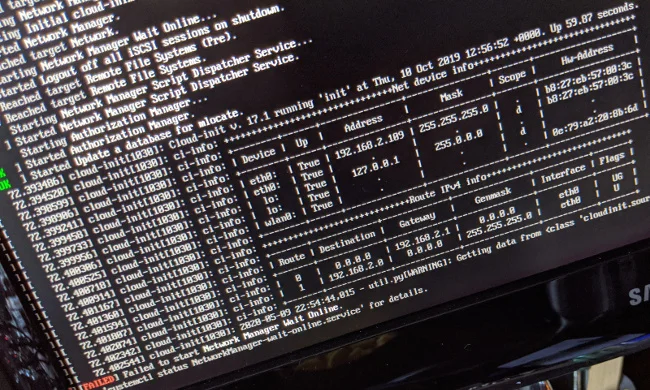

Boot process for a Linux server running Cloud-init (Chris Collins, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Admittedly, Cloud-init is more useful for a cloud provider provisioning machines for many different clients than for a homelab run by a single sysadmin, and much of what Cloud-init solves might be a little superfluous for a homelab. However, getting it set up and learning how it works is a great way to learn more about this cloud technology, not to mention that it's a great way to configure your devices on first boot.

This tutorial uses Cloud-init's "NoCloud" datasource, which allows Cloud-init to be used outside a traditional cloud provider setting. This article will show you how to install Cloud-init on a client device and set up a container running a web service to respond to the client's requests. You will also learn to investigate what the client is requesting from the web service and modify the web service's container to serve a basic, static Cloud-init service.

Set up Cloud-init on an existing system

Cloud-init probably is most useful on a new system's first boot to query for configuration data and make changes to customize the system as directed. It can be included in a disk image for Raspberry Pis and single-board computers or added to images used to provision virtual machines. For testing, it is easy to install and run Cloud-init on an existing system or to install a new system and then set up Cloud-init.

As a major service used by most cloud providers, Cloud-init is supported on most Linux distributions. For this example, I will be using Fedora 31 Server for the Raspberry Pi, but it can be done the same way on Raspbian, Ubuntu, CentOS, and most other distributions.

Install and enable the cloud-init services

On a system that you want to be a Cloud-init client, install the Cloud-init package. If you're using Fedora:

# Install the cloud-init package

dnf install -y cloud-initCloud-init is actually four different services (at least with systemd), and each is in charge of retrieving config data and performing configuration changes during a different part of the boot process, allowing greater flexibility in what can be done. While it is unlikely you will interact much with these services directly, it is useful to know what they are in the event you need to troubleshoot something. They are:

- cloud-init-local.service

- cloud-init.service

- cloud-config.service

- cloud-final.service

Enable all four services:

# Enable the four cloud-init services

systemctl enable cloud-init-local.service

systemctl enable cloud-init.service

systemctl enable cloud-config.service

systemctl enable cloud-final.serviceConfigure the datasource to query

Once the service is enabled, configure the datasource from which the client will query the config data. There are a large number of datasource types, and most are configured for specific cloud providers. For your homelab, use the NoCloud datasource, which (as mentioned above) is designed for using Cloud-init without a cloud provider.

NoCloud allows configuration information to be included a number of ways: as key/value pairs in kernel parameters, for using a CD (or virtual CD, in the case of virtual machines) mounted at startup, in a file included on the filesystem, or, as in this example, via HTTP from a specified URL (the "NoCloud Net" option).

The datasource configuration can be provided via the kernel parameter or by setting it in the Cloud-init configuration file, /etc/cloud/cloud.cfg. The configuration file works very well for setting up Cloud-init with customized disk images or for testing on existing hosts.

Cloud-init will also merge configuration data from any *.cfg files found in /etc/cloud/cloud.cfg.d/, so to keep things cleaner, configure the datasource in /etc/cloud/cloud.cfg.d/10_datasource.cfg. Cloud-init can be told to read from an HTTP datasource with the seedfrom key by using the syntax:

seedfrom: https://ip_address:port/The IP address and port are the web service you will create later in this article. I used the IP of my laptop and port 8080; this can also be a DNS name.

Create the /etc/cloud/cloud.cfg.d/10_datasource.cfg file:

# Add the datasource:

# /etc/cloud/cloud.cfg.d/10_datasource.cfg

# NOTE THE TRAILING SLASH HERE!

datasource:

NoCloud:

seedfrom: https://ip_address:port/That's it for the client setup. Now, when the client is rebooted, it will attempt to retrieve configuration data from the URL you entered in the seedfrom key and make any configuration changes that are necessary.

The next step is to set up a webserver to listen for client requests, so you can figure out what needs to be served.

Set up a webserver to investigate client requests

You can create and run a webserver quickly with Podman or other container orchestration tools (like Docker or Kubernetes). This example uses Podman, but the same commands work with Docker.

To get started, use the Fedora:31 container image and create a Containerfile (for Docker, this would be a Dockerfile) that installs and configures Nginx. From that Containerfile, you can build a custom image and run it on the host you want to act as the Cloud-init service.

Create a Containerfile with the following contents:

FROM fedora:31

ENV NGINX_CONF_DIR "/etc/nginx/default.d"

ENV NGINX_LOG_DIR "/var/log/nginx"

ENV NGINX_CONF "/etc/nginx/nginx.conf"

ENV WWW_DIR "/usr/share/nginx/html"

# Install Nginx and clear the yum cache

RUN dnf install -y nginx \

&& dnf clean all \

&& rm -rf /var/cache/yum

# forward request and error logs to docker log collector

RUN ln -sf /dev/stdout ${NGINX_LOG_DIR}/access.log \

&& ln -sf /dev/stderr ${NGINX_LOG_DIR}/error.log

# Listen on port 8080, so root privileges are not required for podman

RUN sed -i -E 's/(listen)([[:space:]]*)(\[\:\:\]\:)?80;$/\1\2\38080 default_server;/' $NGINX_CONF

EXPOSE 8080

# Allow Nginx PID to be managed by non-root user

RUN sed -i '/user nginx;/d' $NGINX_CONF

RUN sed -i 's/pid \/run\/nginx.pid;/pid \/tmp\/nginx.pid;/' $NGINX_CONF

# Run as an unprivileged user

USER 1001

CMD ["nginx", "-g", "daemon off;"]Note: The example Containerfile and other files used in this example can be found in this project's GitHub repository.

The most important part of the Containerfile above is the section that changes how the logs are stored (writing to STDOUT rather than a file), so you can see requests coming into the server in the container logs. A few other changes enable you to run the container with Podman without root privileges and to run processes in the container without root, as well.

This first pass at the webserver does not serve any Cloud-init data; just use this to see what the Cloud-init client is requesting from it.

With the Containerfile created, use Podman to build and run a webserver image:

# Build the container image

$ podman build -f Containerfile -t cloud-init:01 .

# Create a container from the new image, and run it

# It will listen on port 8080

$ podman run --rm -p 8080:8080 -it cloud-init:01This will run the container, leaving your terminal attached and with a pseudo-TTY. It will appear that nothing is happening at first, but requests to port 8080 of the host machine will be routed to the Nginx server inside the container, and a log message will appear in the terminal window. This can be tested with a curl command from the host machine:

# Use curl to send an HTTP request to the Nginx container

$ curl https://localhost:8080After running that curl command, you should see a log message similar to this in the terminal window:

127.0.0.1 - - [09/May/2020:19:25:10 +0000] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 5564 "-" "curl/7.66.0" "-"Now comes the fun part: reboot the Cloud-init client and watch the Nginx logs to see what Cloud-init requests from the webserver when the client boots up.

As the client finishes its boot process, you should see log messages similar to:

2020/05/09 22:44:28 [error] 2#0: *4 open() "/usr/share/nginx/html/meta-data" failed (2: No such file or directory), client: 127.0.0.1, server: _, request: "GET /meta-data HTTP/1.1", host: "instance-data:8080"

127.0.0.1 - - [09/May/2020:22:44:28 +0000] "GET /meta-data HTTP/1.1" 404 3650 "-" "Cloud-Init/17.1" "-"Note: Use Ctrl+C to stop the running container.

You can see the request is for the /meta-data path, i.e., https://ip_address_of_the_webserver:8080/meta-data. This is just a GET request—Cloud-init is not POSTing (sending) any data to the webserver. It is just blindly requesting the files from the datasource URL, so it is up to the datasource to identify what the host is asking. This simple example is just sending generic data to any client, but a larger homelab will need a more sophisticated service.

Here, Cloud-init is requesting the instance metadata information. This file can include a lot of information about the instance itself, such as the instance ID, the hostname to assign the instance, the cloud ID—even networking information.

Create a basic metadata file with an instance ID and a hostname for the host, and try serving that to the Cloud-init client.

First, create a metadata file that can be copied into the container image:

instance-id: iid-local01

local-hostname: raspberry

hostname: raspberryThe instance ID can be anything. However, if you change the instance ID after Cloud-init runs and the file is served to the client, it will trigger Cloud-init to run again. You can use this mechanism to update instance configurations, but you should be aware that it works that way.

The local-hostname and hostname keys are just that; they set the hostname information for the client when Cloud-init runs.

Add the following line to the Containerfile to copy the metadata file into the new image:

# Copy the meta-data file into the image for Nginx to serve it

COPY meta-data ${WWW_DIR}/meta-dataNow, rebuild the image (use a new tag for easy troubleshooting) with the metadata file, and create and run a new container with Podman:

# Build a new image named cloud-init:02

podman build -f Containerfile -t cloud-init:02 .

# Run a new container with this new meta-data file

podman run --rm -p 8080:8080 -it cloud-init:02With the new container running, reboot your Cloud-init client and watch the Nginx logs again:

127.0.0.1 - - [09/May/2020:22:54:32 +0000] "GET /meta-data HTTP/1.1" 200 63 "-" "Cloud-Init/17.1" "-"

2020/05/09 22:54:32 [error] 2#0: *2 open() "/usr/share/nginx/html/user-data" failed (2: No such file or directory), client: 127.0.0.1, server: _, request: "GET /user-data HTTP/1.1", host: "instance-data:8080"

127.0.0.1 - - [09/May/2020:22:54:32 +0000] "GET /user-data HTTP/1.1" 404 3650 "-" "Cloud-Init/17.1" "-"You see that this time the /meta-data path was served to the client. Success!

However, the client is looking for a second file at the /user-data path. This file contains configuration data provided by the instance owner, as opposed to data from the cloud provider. For a homelab, both of these are you.

There are a large number of user-data modules you can use to configure your instance. For this example, just use the write_files module to create some test files on the client and verify that Cloud-init is working.

Create a user-data file with the following content:

#cloud-config

# Create two files with example content using the write_files module

write_files:

- content: |

"Does cloud-init work?"

owner: root:root

permissions: '0644'

path: /srv/foo

- content: |

"IT SURE DOES!"

owner: root:root

permissions: '0644'

path: /srv/barIn addition to a YAML file using the user-data modules provided by Cloud-init, you could also make this an executable script for Cloud-init to run.

After creating the user-data file, add the following line to the Containerfile to copy it into the image when the image is rebuilt:

# Copy the user-data file into the container image

COPY user-data ${WWW_DIR}/user-dataRebuild the image and create and run a new container, this time with the user-data information:

# Build a new image named cloud-init:03

podman build -f Containerfile -t cloud-init:03 .

# Run a new container with this new user-data file

podman run --rm -p 8080:8080 -it cloud-init:03Now, reboot your Cloud-init client, and watch the Nginx logs on the webserver:

127.0.0.1 - - [09/May/2020:23:01:51 +0000] "GET /meta-data HTTP/1.1" 200 63 "-" "Cloud-Init/17.1" "-"

127.0.0.1 - - [09/May/2020:23:01:51 +0000] "GET /user-data HTTP/1.1" 200 298 "-" "Cloud-Init/17.1" "-Success! This time both the metadata and user-data files were served to the Cloud-init client.

Validate that Cloud-init ran

From the logs above, you know that Cloud-init ran on the client host and requested the metadata and user-data files, but did it do anything with them? You can validate that Cloud-init wrote the files you added in the user-data file, in the write_files section.

On your Cloud-init client, check the contents of the /srv/foo and /srv/bar files:

# cd /srv/ && ls

bar foo

# cat foo

"Does cloud-init work?"

# cat bar

"IT SURE DOES!"

Success! The files were written and have the content you expect.

As mentioned above, there are plenty of other modules that can be used to configure the host. For example, the user-data file can be configured to add packages with apt, copy SSH authorized_keys, create users and groups, configure and run configuration-management tools, and many other things. I use it in my private cloud at home to copy my authorized_keys, create a local user and group, and set up sudo permissions.

What you can do next

Cloud-init is useful in a homelab, especially a lab focusing on cloud technologies. The simple service demonstrated in this article may not be super useful for a homelab, but now that you know how Cloud-init works, you can move on to creating a dynamic service that can configure each host with custom data, making a private cloud at home more similar to the services provided by the major cloud providers.

With a slightly more complicated datasource, adding new physical (or virtual) machines to your private cloud at home can be as simple as plugging them in and turning them on.

1 Comment