A master was explaining the nature of The Tao of Programming to one of his novices. "The Tao is embodied in all software—regardless of how insignificant," said the master.

"Is Tao in a hand-held calculator?" asked the novice.

"It is," came the reply.

"Is the Tao in a video game?" continued the novice.

"It is even in a video game," said the master.

"And is the Tao in the DOS for a personal computer?"

The master coughed and shifted his position slightly. "The lesson is over for today," he said.

The Tao of Programming, Geoffrey James, InfoBooks, 1987

Computing used to be limited only to expensive mainframes and "Big Iron" computer systems like the PDP11. But the advent of the microprocessor brought about a computing revolution in the 1970s. You could finally have a computer in your home—the "personal computer" had arrived!

The earliest personal computers I remember seeing included the Commodore, TRS-80, and Apple. The personal computer became such a hot topic that IBM decided to enter the market. After a rapid development cycle, IBM released the IBM 5150 Personal Computer (the original "IBM PC") in August 1981.

Creating a computer from scratch is no easy task, so IBM famously used "off-the-shelf" hardware to build the PC, and licensed other components from outside developers. One of those was the operating system, licensed from Microsoft. In turn, Microsoft acquired 86-DOS from Seattle Computer Products, applied various updates, and debuted the new version with the IBM PC as IBM PC-DOS.

Early DOS

Running in memory up to 640 kilobytes, DOS really couldn't do much more than manage the hardware and allow the user to launch applications. As a result, the PC-DOS 1.0 command line was pretty anemic, only including a few commands to set the date and time, manage files, control the terminal, and format floppy disks. DOS also included a BASIC language interpreter, which was a standard feature in all personal computers of the era.

It wasn't until PC-DOS 2.0 that DOS became more interesting, adding new commands to the command line, and including other useful tools. But for me, it wasn't until MS-DOS 5.0 in 1991 that DOS began to feel "modern." Microsoft overhauled DOS in this release, updating many of the commands and replacing the venerable Edlin editor with a new full-screen editor that was more user-friendly. DOS 5 included other features that I liked, as well, such as a new BASIC interpreter based on Microsoft QuickBASIC Compiler, simply called QBASIC. If you've ever played the Gorillas game on DOS, it was probably in MS-DOS 5.0.

Despite these upgrades, I wasn't entirely satisfied with the DOS command line. DOS never strayed far from the original design, which proved limiting. DOS gave the user a few tools to do some things from the command line—otherwise, you were meant to use the DOS command line to launch applications. Microsoft assumed the user would spend most of their time in a few key applications, such as a word processor or spreadsheet.

But developers wanted a more functional DOS, and a sub-industry sprouted to offer neat tools and programs. Some were full-screen applications, but many were command-line utilities that enhanced the DOS command environment. When I learned a bit of C programming, I started writing my own utilities that extended or replaced the DOS command line. And despite the rather limited underpinnings of MS-DOS, I found that the third-party utilities, plus my own, created a powerful DOS command line.

FreeDOS

In early 1994, I started seeing a lot of interviews with Microsoft executives in tech magazines saying the next version of Windows would totally do away with DOS. I'd used Windows before—but if you remember the era, you know Windows 3.1 wasn't a great platform. Windows 3.1 was clunky and buggy—if an application crashed, it might take down the entire Windows system. And I didn't like the Windows graphical user interface, either. I preferred doing my work at the command line, not with a mouse.

I considered Windows and decided, If Windows 3.2 or Windows 4.0 will be anything like Windows 3.1, I want nothing to do with it.

But what were my options? I'd already experimented with Linux at this point, and thought Linux was great—but Linux didn't have any applications. My word processor, spreadsheet, and other programs were on DOS. I needed DOS.

Then I had an idea! I thought, If developers can come together over the internet to write a complete Unix operating system, surely we can do the same thing with DOS.

After all, DOS was a fairly straightforward operating system compared to Unix. DOS ran one task at a time (single-tasking) and had a simpler memory model. It shouldn't be that hard to write our own DOS.

So on June 29, 1994, I posted an announcement to comp.os.msdos.apps, on a message board network called Usenet:

ANNOUNCEMENT OF PD-DOS PROJECT:

A few months ago, I posted articles relating to starting a public domain version of DOS. The general support for this at the time was strong, and many people agreed with the statement, "start writing!" So, I have...

Announcing the first effort to produce a PD-DOS. I have written up a "manifest" describing the goals of such a project and an outline of the work, as well as a "task list" that shows exactly what needs to be written. I'll post those here, and let discussion follow.

* A note about the name—I wanted this new DOS to be something that everyone could use, and I naively assumed that when everyone could use it, it was "public domain." I quickly realized the difference, and we renamed "PD-DOS" to "Free-DOS"—and later dropped the hyphen to become "FreeDOS."

A few developers reached out to me, to offer utilities they had created to replace or enhance the DOS command line, similar to my own efforts. We pooled our utilities and created a useful system that we released as "Alpha 1" in September 1994, just a few months after announcing the project. Development was pretty swift in those days, and we followed up with "Alpha 2" in December 1994, "Alpha 3" in January 1995, and "Alpha 4" in June 1995.

A modern DOS

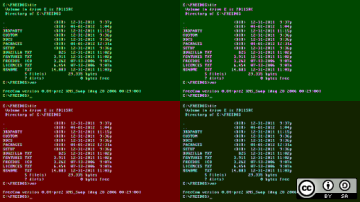

Since then, we've always focused on making FreeDOS a "modern" DOS. And much of that modernization is centered on creating a rich command-line environment. Yes, DOS still needs to support applications, but we believe FreeDOS needs a strong command-line environment, as well. That's why FreeDOS includes dozens of useful tools, including commands to navigate directories, manage files, play music, connect to networks, ... and a collection of Unix-like utilities such as less, du, head, tail, sed, and tr.

While FreeDOS development has slowed, it has not stopped. Developers continue to write new programs for FreeDOS, and add new features to FreeDOS. I'm particularly excited about several great additions to FreeDOS 1.3 RC4, the latest release candidate for the forthcoming FreeDOS 1.3. A few recent updates:

- Mateusz Viste created a new ebook reader called Ancient Machine Book (AMB) that we've leveraged as the new help system in FreeDOS 1.3 RC4

- Rask Ingemann Lambertsen, Andrew Jenner, TK Chia, and others are updating the IA-16 version of GCC, including a new libi86 library that provides some degree of compatibility with the Borland Turbo C++ compiler's C library

- Jason Hood has updated an unloadable CD-ROM redirector substitute for Microsoft's MSCDEX, supporting up to 10 drives

- SuperIlu has created DOjS, a Javascript development canvas with an integrated editor, graphics and sound output, and mouse, keyboard, and joystick input

- Japheth has created a DOS32PAE extender that is able to use huge amounts of memory through PAE paging

Despite all of the new development on FreeDOS, we remain true to our DOS roots. As we continue working toward FreeDOS 1.3 "final," we carry several core assumptions, including:

- Compatibility is key—FreeDOS isn't really "DOS" if it can't run classic DOS applications. While we provide many great open source tools, applications, and games, you can run your legacy DOS applications, too.

- Continue to run on old PCs (XT, '286, '386, etc)—FreeDOS 1.3 will remain 16-bit Intel but will support new hardware with expanded driver support, where possible. For this reason, we continue to focus on a single-user command-line environment.

- FreeDOS is open source software—I've always said that FreeDOS isn't a "free DOS" if people can't access, study, and modify the source code. FreeDOS 1.3 will include software that uses recognized open source licenses as much as possible. But DOS actually pre-dates the GNU General Public License (1989) and the Open Source Definition (1998) so some DOS software might use its own "free with source code" license that isn't a standard "open source" license. As we consider packages to include in FreeDOS, we continue to evaluate any licenses to ensure they are suitably "open source," even if they are not officially recognized.

We welcome your help in making FreeDOS great! Please join us on our email list—we welcome all newcomers and contributors. We communicate over an email list, but the list is fairly low volume so is unlikely to fill up your Inbox.

Visit the FreeDOS website at www.freedos.org.

1 Comment