There is a sea of game engines available on the internet. Some specialize in 2D, some 3D. The languages vary. Some are Java based, Javascript, C#, C++, or perhaps their own special scripting language. The licenses vary. Some are free to use but pay on sales. Some are completely free to do anything you like with.

Some have large communities, rich toolsets, and big businesses behind them. And very occasionally, you come across a project in a quiet corner of the internet that just ticks all the right boxes. Yet, the majority of the crowd has simply passed it by.

Orx is one such project.

Developed since 2007, and with roots going back to 2002, Orx is an engine for C, C++, or Objective-C developers to create top performance 2D games. There are two sides to this little engine. One side is the clean code of the API, developed entirely in C, but with an object-orientated design. The other side is something quite clever: the configuration system.

The configuration system is designed to replace large chunks of code, timers, and event listeners with user-defined data configuration. Yes, that is a major mouthful and probably does little to describe what it is for.

It would be better to describe a typical game development scenario, and how Orx's configuration system could make the task much easier.

Coding

Imagine you want to destroy an alien on the screen. You would place an explosion sprite on top of your alien ship, then destroy the alien ship itself. If the explosion object triggered a few smaller explosion objects, you would need a loop to create them all, then set up events to track each one and update their positions. Your event code would then also need to time the life of the explosion and sub-explosions and remove them after their lifetime has been exceeded.

That's a lot of complicated code. How can Orx deal with this in a better way and make the developer's life easier? By constructing object configuration that would resemble something like this:

ExplosionObject

ExplosionObjectGraphic

Spawner

SpawnerObject

SpawnerObjectGraphic

Direction: 360 degrees random, 5 units of velocity

LifeTime: 2 seconds

FadeOutToAlphaFX

FadeOutToAlphaFX

LifeTime: 1 secondThis is pseudo-configuration. But it simply means: define an object with a graphic. Give it a spawner. The spawner will expel Spawner Objects, which in turn have their own graphic. But send these objects in any direction with a certain speed, only live for two seconds each, and fade out before being removed.

In the same way, the main object will also fade out before being removed after one second.

The upshot of all this is: Create a single ExplosionObject on the screen, and everything defined under it will happen automatically for you. No code to manage the object if you don't want to. No code to track its lifetime or what it is expected to do.

That is the absolute beauty of Orx's configuration system in one small but complicated example. But that is only the tip of the iceberg in terms of what power is available to the indie game developer.

Community

Orx has a very small, but friendly community. There is a forum, as you would expect, with many years of advice and answers to developer questions. The forum acts as a treasure trove of information and tips.

In recent times, the Orx community has opened an active chat room on Gitter. This has helped accelerate changes to the Orx engine and Orx-based projects and games, as well as enabled faster communication between users.

The head of the community is Romain Killian, the developer of Orx. Rom has been on hand, supporting the community for years. AI game development is his day job. He is held in high regard, having worked for the likes of Ubisoft and Nihilistic. He's also incredibly friendly and humble. This has been one of the major drawcards for myself and others to be enticed into the community and play active roles. Rom's support for his users has led to the community expanding the Orx wiki into an active learning center where examples and tutorials for using Orx are there in abundance. The lists grow every week.

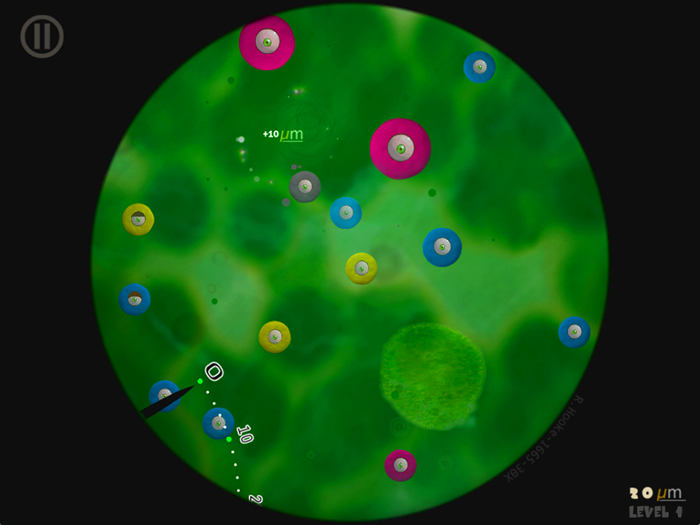

Little Cells. Fully Bugged, CC BY

Small fish in a big pond

While the majority of indie developers head almost immediately in the direction of C# and Unity, largely based on the influence and recommendation of fellow developers, Orx is different. It is a C-based engine and can outperform the output from Unity in many respects.

Choosing for higher performance does come at a cost. The Orx community is smaller. Therefore there are none of the game-builder style tools that you expect to come packaged with offerings like Unity. One could argue that with the configuration system that Orx offers, editors are simply not necessary.

But this doesn't sit well when you are used to designing with an editor and have come to rely on it. While such an offering would be beneficial, it is not a deal breaker when developing a game in Orx.

That is not to say there are no tools for Orx. Many tools like Inkscape, Tiled MapEditor, or DarkFunction sprite animation editor can be used, and converters are available for all these. Also, Orx does have its own editor dedicated to the design of alien wave formations for games in the style of Galaga, 1942, or Raiden.

Endless Flip Runner. Volcano Mobile, CC BY

Speed

Did I mention that Orx is fast? Very fast. The engine is very well optimized. Games written with Orx have been tested at 1920 x 1080 doing a solid 60FPS on an Intel NUC with a Pentium N3700 CPU/Intel HD Graphics. I am not sure of other engines that can match these low-end specs.

Of course, on higher spec'ed machines, the performance is outstanding.

Flexibility

There are no set patterns to using Orx, there are no hidden gotchas. You would be hard pressed to find a 2D game development concept that Orx cannot support. You won't get weeks into a project and discover that there is something missing from the engine. No dealbreakers.

Features you would expect from a top-shelf engine are there: graphics, animation, sound, shaders, events, clocks and timelines, file IO, effects, fonts, input, physics, and of course the configuration system. There's a lot more than this of course. To get a full appreciation of what is available, the API is available online.

Freedom

Orx is not attached to any company or business interest. You can simply take the engine, develop whatever you like for whatever platform, and sell your game in any way without any acknowledgment to Orx whatsoever.

What's the catch? Well, nothing.

You're simply free to do what you like. However, acknowledgment of the engine in your game is always a polite way to say thank you.

This is in contrast to other engines that are backed with a commercial interest and are in strong competition with each other. Many of these pay models allow you to use and develop on an engine for free, but only pay royalties after so many thousand sales. That's not a bad deal. But it's not complete freedom either.

Horses for courses.

Final words

It has been interesting to welcome newcomers to Orx over the years. Some stay and some move on. Many head off with the crowd to the likes of Unity or Löve. But while the bigger name engines fight it out in the public arena, the quiet engine on the fringe of the internet will keep doing what it has been doing best for years.

The small Orx community will keep meeting up and churning out games for desktop and mobile.

And of course, the door is always open to welcome new indie developers who are keen to try their hand on the best little C/C++ based 2D engine there is.

Get started

If you are interested in writing games with Orx, a Beginner's Guide is available on the learning wiki. This will guide you to downloading and setting up Orx then writing a simple game.

The forum contains a lot of help and advice. There are examples and tutorials on the wiki. The Gitter chat room is great for live help from the community.

You can get the latest Orx news from the official website or the Twitter feed.

7 Comments