I first installed Linux in 1993. I ran MS-DOS at the time, but I really liked the Unix systems in our campus computer lab, where I spent much of my time as an undergraduate university student. When I heard about Linux, a free version of Unix that I could run on my 386 computer at home, I immediately wanted to try it out. My first Linux distribution was Softlanding Linux System (SLS) 1.03, with Linux kernel 0.99 alpha patch level 11. That required a whopping 2MB of RAM, or 4MB if you wanted to compile programs, and 8MB to run X windows.

I thought Linux was a huge step up from the world of MS-DOS. While Linux lacked the breadth of applications and games available on MS-DOS, I found Linux gave me a greater degree of flexibility. Unlike MS-DOS, I could now do true multi-tasking, running more than one program at a time. And Linux provided a wealth of tools, including a C compiler that I could use to build my own programs.

A year later, I upgraded to SLS 1.05, which sported the brand-new Linux kernel 1.0. More importantly, Linux 1.0 introduced kernel modules. With modules, you no longer needed to completely recompile your kernel to support new hardware; instead you loaded one of the 63 included Linux kernel modules. SLS 1.05 included this note about modules in the distribution's README file:

Modularization of the kernel is aimed squarely at reducing, and eventually eliminating, the requirements for recompiling the kernel, either for changing/modifying device drivers or for dynamic access to infrequently required drivers. More importantly, perhaps, the efforts of individual working groups need no longer affect the development of the kernel proper. In fact, a binary release of the official kernel should now be possible.

On August 25, the Linux kernel will reach its 26th anniversary. To celebrate, I reinstalled SLS 1.05 to remind myself what the Linux 1.0 kernel was like and to recognize how far Linux has come since the 1990s. Join me on this journey into Linux nostalgia!

Installation

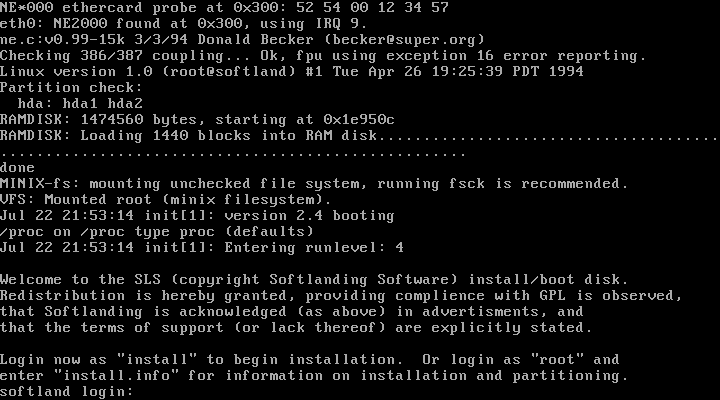

Softlanding Linux System was the first true "distribution" that included an install program. Yet the install process isn't the same smooth process you find in modern distributions. Instead of booting from an install CD-ROM, I needed to boot my system from an install floppy, then run the install program from the login prompt.

opensource.com

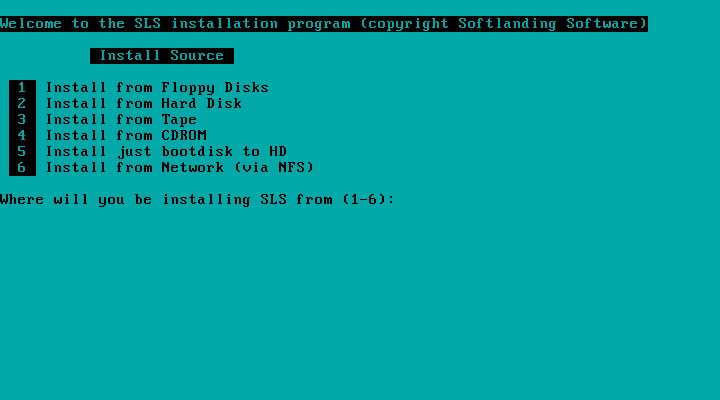

A neat feature introduced in SLS 1.05 was the color-enabled text-mode installer. When I selected color mode, the installer switched to a light blue background with black text, instead of the plain white-on-black text used by our primitive forbearers.

opensource.com

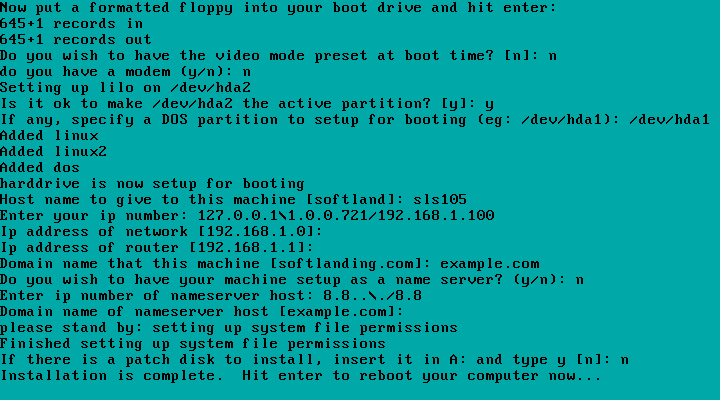

The SLS installer is a simple affair, scrolling text from the bottom of the screen, but it does the job. By responding to a few simple prompts, I was able to create a partition for Linux, put an ext2 filesystem on it, and install Linux. Installing SLS 1.05, including X windows and development tools, required about 85MB of disk space. That may not sound like much space by today's standards, but when Linux 1.0 came out, 120MB hard drives were still common.

opensource.com

opensource.com

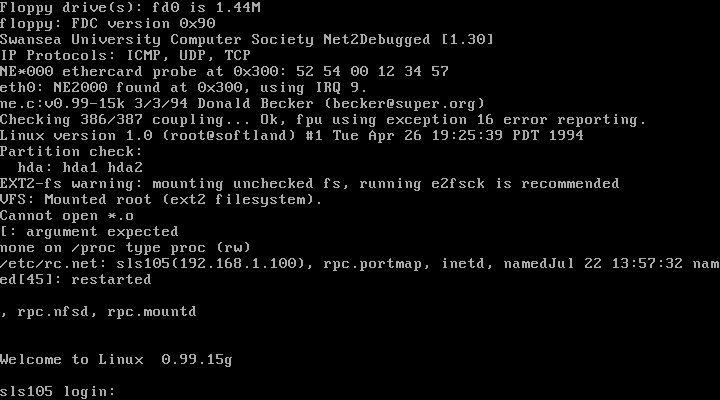

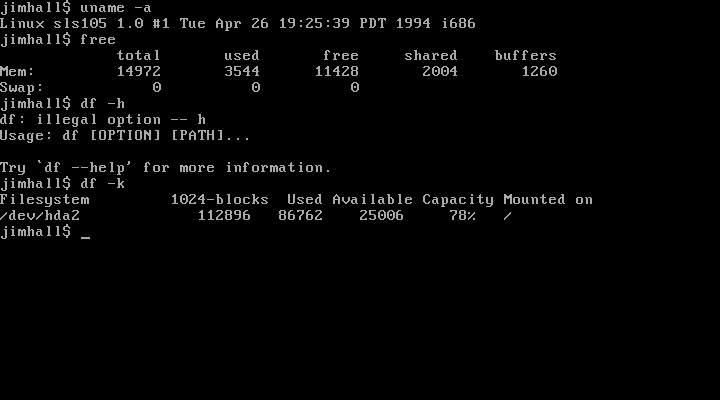

System level

When I first booted into Linux, my memory triggered a few system things about this early version of Linux. First, Linux doesn't take up much space. After booting the system and running a few utilities to check it out, Linux occupied less than 4MB of memory. On a system with 16MB of memory, that meant lots left over to run programs.

opensource.com

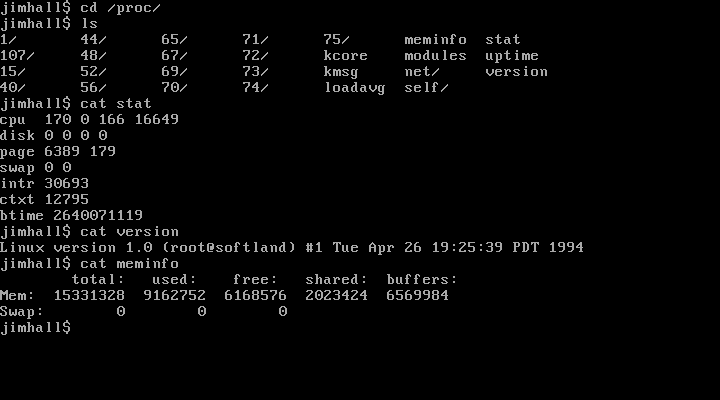

The familiar /proc meta filesystem exists in Linux 1.0, although it doesn't provide much information compared to what you see in modern systems. In Linux 1.0, /proc includes interfaces to probe basic system statistics like meminfo and stat.

opensource.com

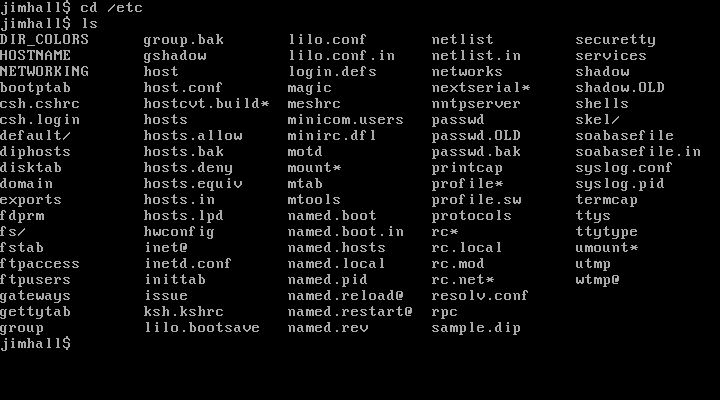

The /etc directory on this system is pretty bare. Notably, SLS 1.05 borrows the rc scripts from BSD Unix to control system startup. Everything gets started via rc scripts, with local system changes defined in the rc.local file. Later, most Linux distributions would adopt the more familiar init scripts from Unix System V, then the systemd initialization system.

opensource.com

What you can do

With my system up and running, it was time to get to work. So, what can you do with this early Linux system?

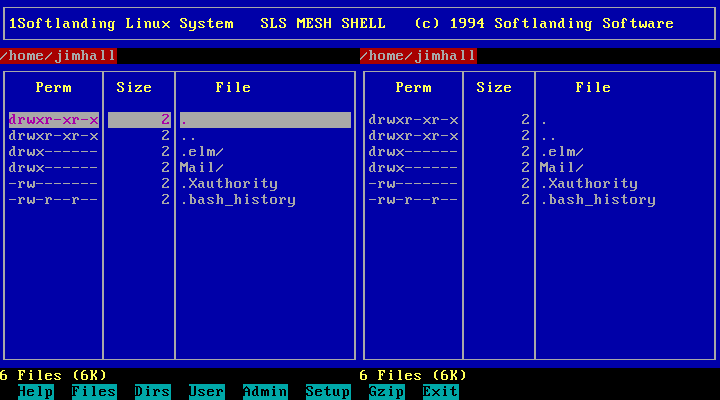

Let's start with basic file management. Every time you log in, SLS reminds you about the Softlanding menu shell (MESH), a file-management program that modern users might recognize as similar to Midnight Commander. Users in the 1990s would have compared MESH more closely to Norton Commander, arguably the most popular third-party file manager available on MS-DOS.

opensource.com

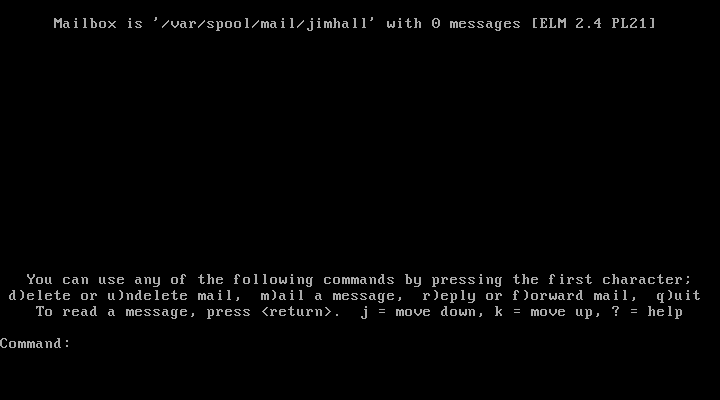

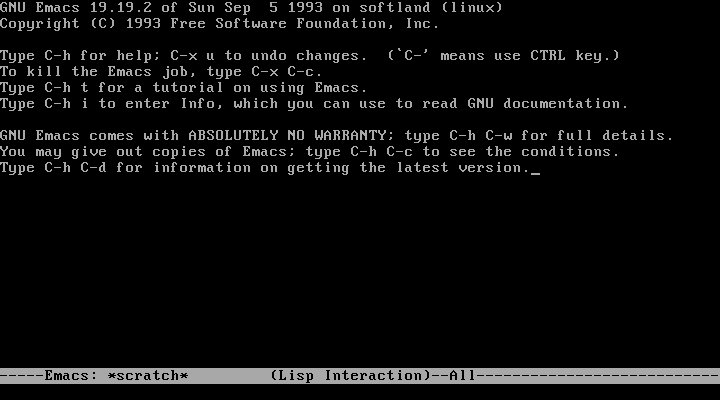

Aside from MESH, there are relatively few full-screen applications included with SLS 1.05. But you can find the familiar user tools, including the Elm mail reader, the GNU Emacs programmable editor, and the venerable Vim editor.

opensource.com

opensource.com

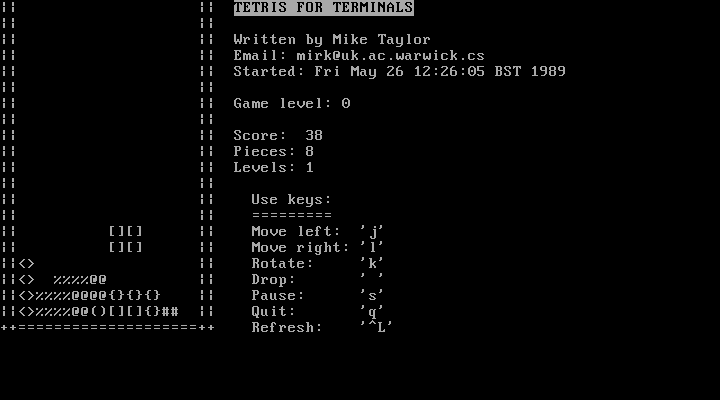

SLS 1.05 even included a version of Tetris that you could play at the terminal.

opensource.com

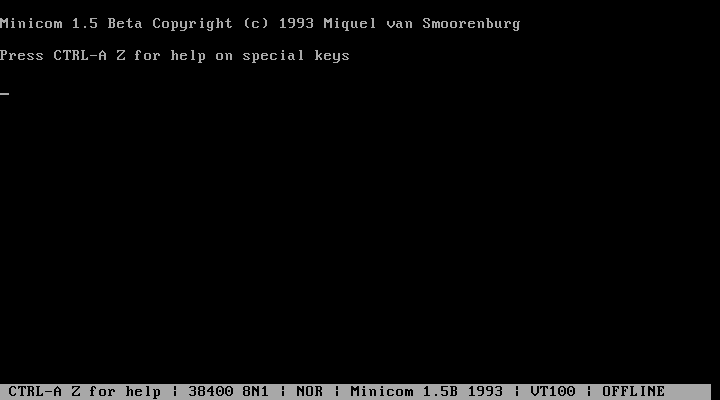

In the 1990s, most residential internet access was via dial-up connections, so SLS 1.05 included the Minicom modem-dialer application. Minicom provided a direct connection to the modem and required users to navigate the Hayes modem AT commands to do basic functions like dial a number or hang up the phone. Minicom also supported macros and other neat features to make it easier to connect to your local modem pool.

opensource.com

But what if you wanted to write a document? SLS 1.05 existed long before the likes of LibreOffice or OpenOffice. Linux just didn't have those applications in the early 1990s. Instead, if you wanted to use a word processor, you likely booted your system into MS-DOS and ran your favorite word processor program, such as WordPerfect or the shareware GalaxyWrite.

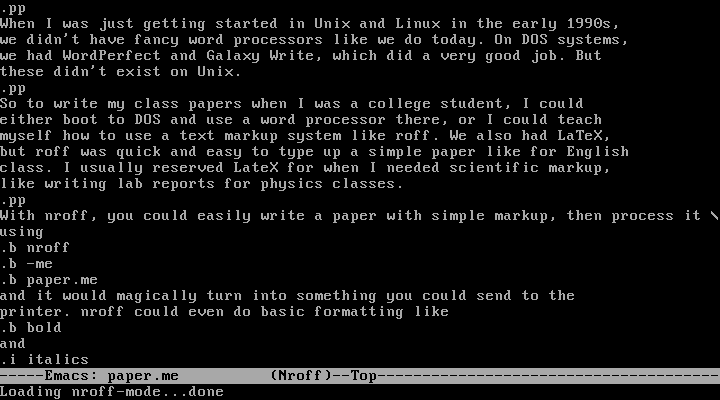

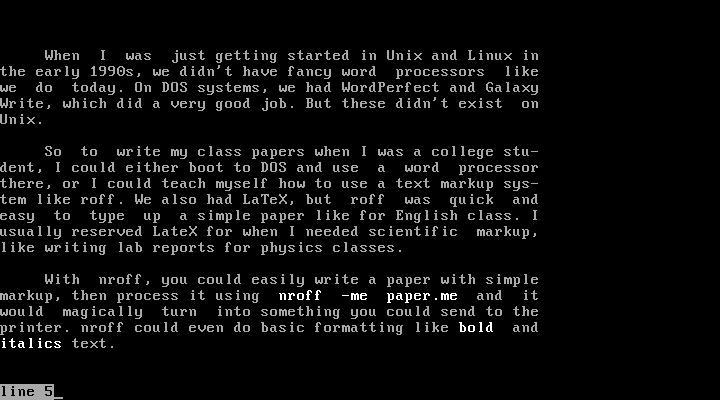

But all Unix systems include a set of simple text formatting programs, called nroff and troff. On Linux systems, these are combined into the GNU groff package, and SLS 1.05 includes a version of groff. One of my tests with SLS 1.05 was to generate a simple text document using nroff.

opensource.com

opensource.com

Running X windows

Getting X windows to perform was not exactly easy, as the SLS install file promised:

Getting X windows to run on your PC can sometimes be a bit of a sobering experience, mostly because there are so many types of video cards for the PC. Linux X11 supports only VGA type video cards, but there are so many types of VGAs that only certain ones are fully supported. SLS comes with two X windows servers. The full color one, XFree86, supports some or all ET3000, ET4000, PVGA1, GVGA, Trident, S3, 8514, Accelerated cards, ATI plus, and others.

The other server, XF86_Mono, should work with virtually any VGA card, but only in monochrome mode. Accordingly, it also uses less memory and should be faster than the color one. But of course it doesn't look as nice.

The bulk of the X windows configuration information is stored in the directory "/usr/X386/lib/X11/". In particular, the file "Xconfig" defines the timings for the monitor and the video card. By default, X windows is set up to use the color server, but you can switch to using the monochrome server x386mono, if the color one gives you trouble, since it should support any standard VGA. Essentially, this just means making /usr/X386/bin/X a link to it.

Just edit Xconfig to set the mouse device type and timings, and enter "startx".

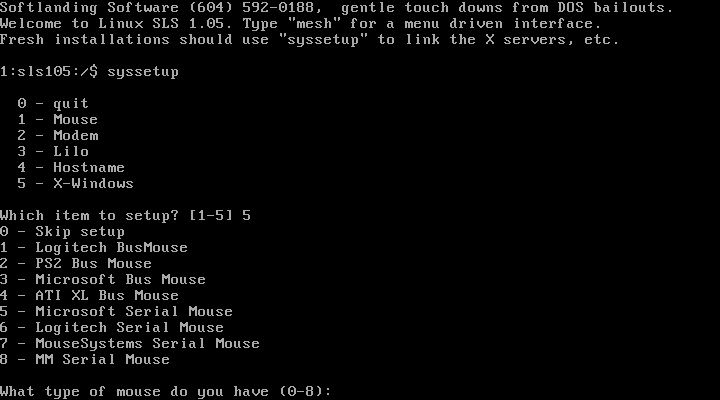

If that sounds confusing, it is. Configuring X windows by hand really can be a sobering experience. Fortunately, SLS 1.05 included the syssetup program to help you define various system components, including display settings for X windows. After a few prompts, and some experimenting and tweaking, I was finally able to launch X windows!

opensource.com

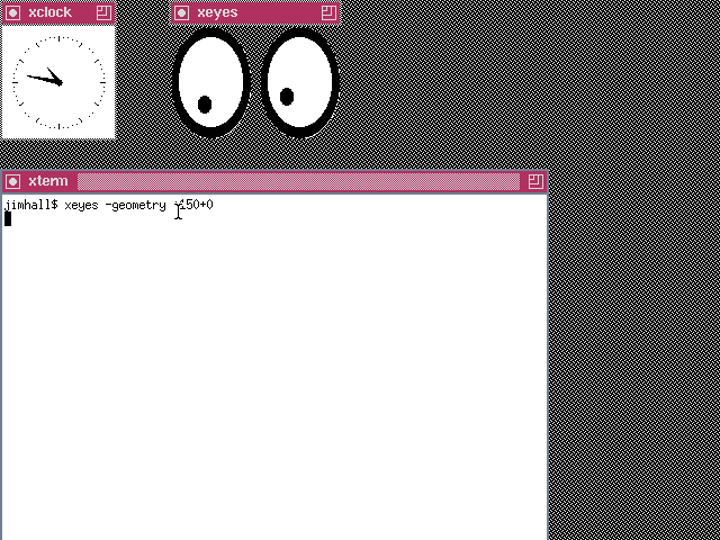

But this is X windows from 1994, and the concept of a desktop didn't exist yet. My options were either FVWM (a virtual window manager) or TWM (the tabbed window manager). TWM was straightforward to set up and provided a simple, yet functional, graphical environment.

opensource.com

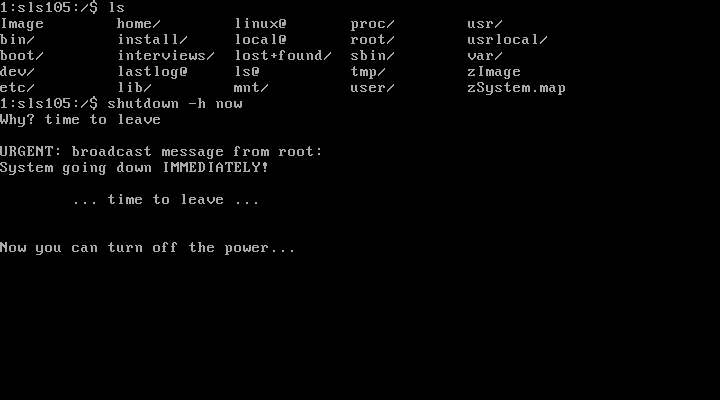

Shutdown

As much as I enjoyed exploring my Linux roots, eventually it was time to return to my modern desktop. I originally ran Linux on a 32-bit 386 computer with just 8MB of memory and a 120MB hard drive, and my system today is much more powerful. I can do so much more on my dual-core, 64-bit Intel Core i5 CPU with 4GB of memory and a 128GB solid-state drive running Linux kernel 4.11.11. So, after my experiments with SLS 1.05 were over, it was time to leave.

opensource.com

So long, Linux 1.0. It's good to see how well you've grown up.

15 Comments