Containers have shifted the way we think about virtualization. You may remember the days (or you may still be living them) when a virtual machine was the full stack, from virtualized BIOS, operating system, and kernel up to each virtualized network interface controller (NIC). You logged into the virtual box just as you would your own workstation. It was a very direct and simple analogy.

And then containers came along, starting with LXC and culminating in the Open Container Initiative (OCI), and that's when things got complicated.

Idempotency

In the world of containers, the "virtual machine" is only mostly virtual. Everything that doesn't need to be virtualized is borrowed from the host machine. Furthermore, the container itself is usually meant to be ephemeral and idempotent, so it stores no persistent data, and its state is defined by configuration files on the host machine.

If you're used to the old ways of virtual machines, then you naturally expect to log into a virtual machine in order to interact with it. But containers are ephemeral, so anything you do in a container is forgotten, by design, should the container need to be restarted or respawned.

The commands controlling your container infrastructure (such as oc, crictl, lxc, and docker) provide an interface to run important commands to restart services, view logs, confirm the existence and permissions modes of an important file, and so on. You should use the tools provided by your container infrastructure to interact with your application, or else edit configuration files and relaunch. That's what containers are designed to do.

For instance, the open source forum software Discourse is officially distributed as a container image. The Discourse software is stateless, so its installation is self-contained within /var/discourse. As long as you have a backup of /var/discourse, you can always restore the forum by relaunching the container. The container holds no persistent data, and its configuration file is /var/discourse/containers/app.yml.

Were you to log into the container and edit any of the files it contains, all changes would be lost if the container had to be restarted.

LXC containers you're building from scratch are more flexible, with configuration files (in a location defined by you) passed to the container when you launch it.

A build system like Jenkins usually has a default configuration file, such as jenkins.yaml, providing instructions for a base container image that exists only to build and run tests on source code. After the builds are done, the container goes away.

Now that you know you don't need SSH to interact with your containers, here's an overview of what tools are available (and some notes about using SSH in spite of all the fancy tools that make it redundant).

OpenShift web console

OpenShift 4 offers an open source toolchain for container creation and maintenance, including an interactive web console.

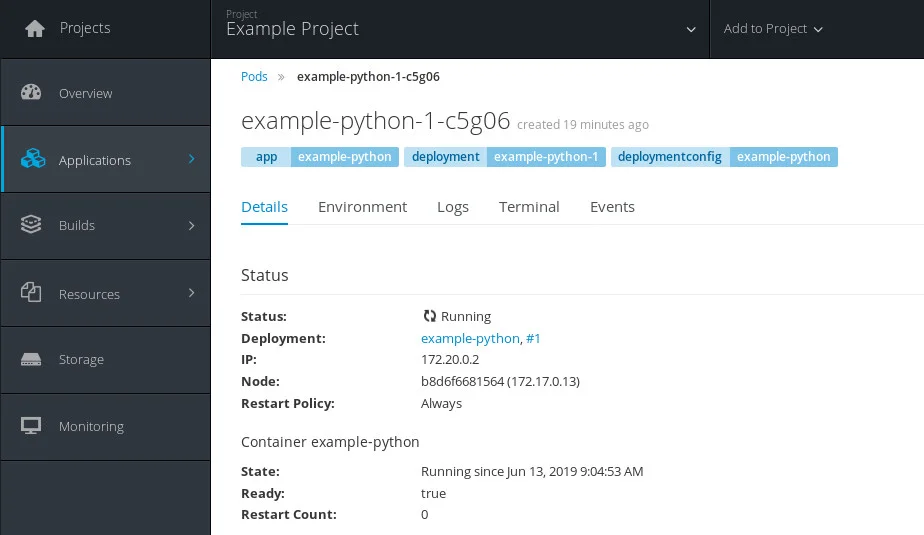

When you log into your web console, navigate to your project overview and click the Applications tab for a list of pods. Select a (running) pod to open the application's Details panel.

opensource.com

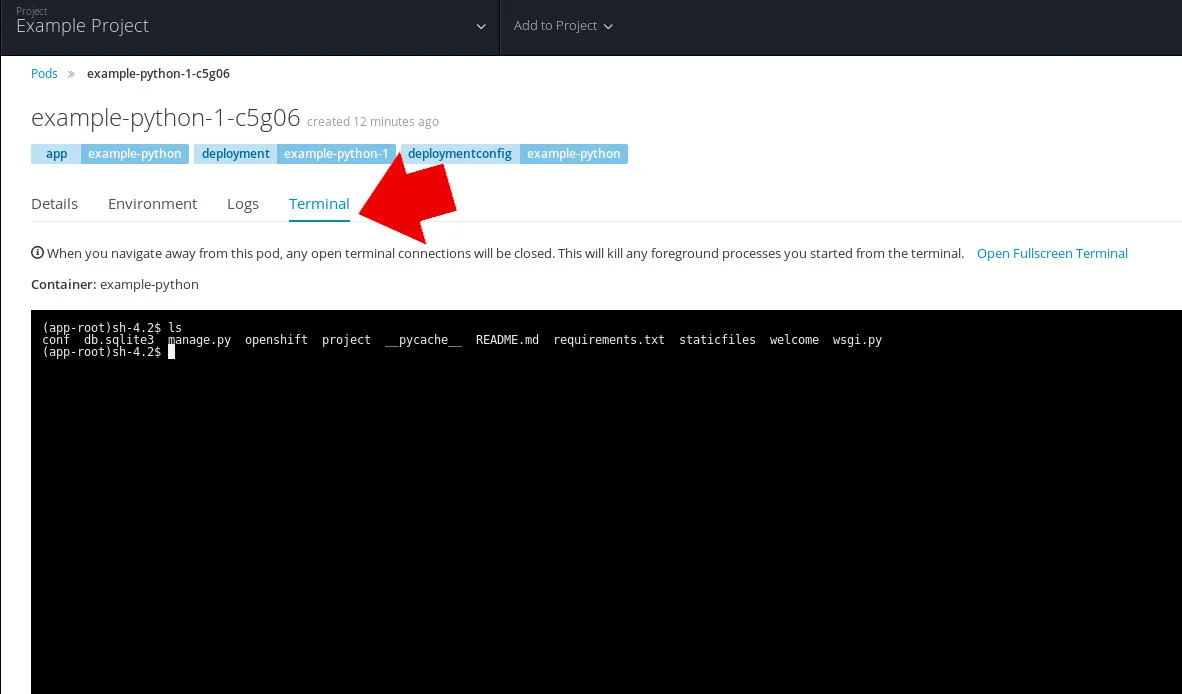

Click the Terminal tab at the top of the Details panel to open an interactive shell in your container.

opensource.com

If you prefer a browser-based experience for Kubernetes management, you can learn more through interactive lessons available at learn.openshift.com.

OpenShift oc

If you prefer a command-line interface experience, you can use the oc command to interact with containers from the terminal.

First, get a list of running pods (or refer to the web console for a list of active pods). To get that list, enter:

$ oc get podsYou can view the logs of a resource (a pod, build, or container). By default, oc logs returns the logs from the first container in the pod you specify. To select a single container, add the --container option:

$ oc logs --follow=true example-1-e1337 --container appYou can also view logs from all containers in a pod with:

$ oc logs --follow=true example-1-e1337 --all-containersExecute commands

You can execute commands remotely with:

$ oc exec example-1-e1337 --container app hostname

example.localThis is similar to running SSH non-interactively: you get to run the command you want to run without an interactive shell taking over your environment.

Remote shell

You can attach to a running container. This still does not open a shell in the container, but it does run commands directly. For example:

$ oc attach example-1-e1337 --container appIf you need a true interactive shell in a container, you can open a remote shell with the oc rsh command as long as the container includes a shell. By default, oc rsh launches /bin/sh:

$ oc rsh example-1-e1337 --container appKubernetes

If you're using Kubernetes directly, you can use the kubetcl exec command to run a Bash shell in your pod.

First, confirm that your pod is running:

$ kubectl get podsAs long as the pod containing your application is listed, you can use the exec command to launch a shell in the container. Using the name example-pod as the pod name, enter:

$ kubectl exec --stdin=false --tty=false

example-pod -- /bin/bash

root@example.local:/# ls

bin core etc lib root srv

boot dev home lib64 sbin tmp varDocker

The docker command is similar to kubectl. With the dockerd daemon running, get the name of the running container (you may have to use sudo to escalate privileges if you're not in the appropriate group):

$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND NAME

678ac5cca78e centos "/bin/bash" example-centosUsing the container name, you can run a command in the container:

$ docker exec example/centos cat /etc/os-release

CentOS Linux release 7.6

NAME="CentOS Linux"

VERSION="7"

ID="centos"

ID_LIKE="rhel fedora"

VERSION_ID="7"

[...]Or you can launch a Bash shell for an interactive session:

$ docker exec -it example-centos /bin/bashContainers and appliances

The important thing to remember when dealing with the cloud is that containers are essentially runtimes rather than virtual machines. While they have much in common with a Linux system (because they are a Linux system!), they rarely translate directly to the commands and workflow you may have developed on your Linux workstation. However, like appliances, containers have an interface to help you develop, maintain, and monitor them, so get familiar with the front-end commands and services until you're happily interacting with them just as easily as you interact with virtual (or bare-metal) machines. Soon, you'll wonder why everything isn't developed to be ephemeral.

6 Comments