Agile continues to take the world by the storm. The latest report from the Standish Group Chaos Study presents interesting findings: Projects based on agile principles have significantly higher success rates than traditional projects based on the waterfall methodology.

In this article, I will try to describe some of the factors that contribute to these high-performance metrics exhibited by agile teams.

What are the reasons for higher success rates in agile?

Almost all waterfall projects I've ever been involved with were strongly biased toward risk-aversion. Waterfall projects typically have sizeable goals in mind and get organized around such goals. Meaning, sizeable resources (monetary and human) get assembled and put into the strictly controlled funnel.

A waterfall project usually begins with: "Listen up, we have high hopes for this new initiative; we have hired awesome experts, invested a lot of money to make sure this goes smoothly. Failure is not an option!"

The team then commences work in all earnestness and is eager to show early results to justify such potentially risky investment. And, as is typically the case, the work commences by focusing on what we call "precision work." What we mean by precision work is early commitments to various aspects of the software product that the team is building. The specifications, the infrastructure, the architecture, the design, all those aspects get firmed up and solidified at the very outset of the project. Once that's vetted and signed off, requirements go into the deep freeze, and the team rushes into writing the code. Eventually, the code is complete (usually after months of frantic work), then comes the code freeze, and now testing commences.

And it is at this stage, when we move into testing, that interesting discoveries start popping up. More often than not, it turns out that the early, eager commitments that cemented the team and product infrastructure only managed to paint the entire project into a proverbial corner. Late (and unavoidable) failure comes at an exorbitant price.

The process I've just described is often called "premature optimization."

Agile turns the above approach on its head. It embraces risks, because of the recognition that, try as we might, risks cannot be avoided. Agile focuses on early feedback (make that extremely early feedback). Replacing the arrogant "we know it all" attitude, agile adopts a humble "we learn along the way" approach.

So, instead of firming up and solidifying the requirements upfront, agile refuses to freeze the scope. Quite the reverse, the agile approach remains fully open to any scope creep. In other words, in an agile project, there is no such thing as scope creep.

Scope in agile is managed by responding to feedback. But how to solicit that precious feedback?

Feedback is always difficult to obtain. Everyone is busy, and no one has the time to volunteer feedback. Also, even if someone manages to find the time to offer their feedback, it often is offered in the spirit of "if you don't have something positive to say, at least abstain from saying anything negative." So, most volunteered feedback ends up being in the form of lukewarm praise.

We are, however, more interested in finding out the truth. So, the only reliable way to solicit valuable feedback is to fail. Failure is a great motivator. It makes all involved parties respond with urgency.

In agile, we value frequent and early failure. We want to expose any significant risks as early as possible. We are open to brutally honest criticism.

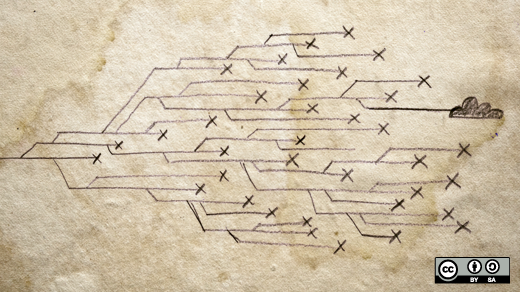

Armed with such an attitude, agile follows the continuous integration (CI) methodology. As we're building a solution, we must attempt to integrate constituent components with each code transformation. Every step of the way is followed by integration testing.

It's the exact opposite with the waterfall approach. Integration is left for the very last step, once everything else has been prematurely optimized, solidified, and tested. It is then at that last stage (integration) where significant risks get discovered. At which point, it is often too late to successfully handle the damage.

How to integrate often and early

The reasons why waterfall methodology is not as successful as agile seem clear. But the underlying causes are not necessarily down to reckless approaches to managing the software development project. The waterfall approach does not arrogantly dismiss early and frequent integration testing. Everyone would love to be able to detect significant risks as early as possible. The issue is with the inability to integrate services and components that are not ready for testing (yet).

As we progress on a project, we prefer to utilize the divide-and-conquer approach. Instead of doing the development and building sequentially (one thing at a time), we naturally prefer to save time by doing as many things as possible in parallel. So, we split the teams into smaller units that specialize in performing dedicated tasks.

However, as those specialized teams are working, they are aware of or are discovering various dependencies. However, as Michael Nygard says in Architecture without an end state: "The problem with dependencies is that you can't depend on them." So the project starts slowing down as it gets bogged down by various dependencies that are not available for integration testing.

The agile approach removes any blockages and allows autonomous teams to continue development activities without having to wait on anyone. This way, integration testing can commence as soon as teams start iterating/sprinting. Agile, in this way, is a huge step forward for IT organizations.

6 Comments