One of Linux's most appealing features is the ability to skillfully use a computer with nothing but commands entered into the keyboard—and better yet, to be able to do that on computers anywhere in the world. Thanks to OpenSSH, POSIX users can open a secure shell on any computer they have permission to access and use it from a remote location. It's a daily task for many Linux users, but it can be confusing for someone who has yet to try it. This article explains how to configure two computers for secure shell (SSH) connections, and how to securely connect from one to the other without a password.

Terminology

When discussing more than one computer, it can be confusing to identify one from the other. The IT community has well-established terms to help clarify descriptions of the process of networking computers together.

- Service: A service is software that runs in the background so it can be used by computers other than the one it's installed on. For instance, a web server hosts a web-sharing service. The term implies (but does not insist) that it's software without a graphical interface.

- Host: A host is any computer. In IT, computers are called a host because technically any computer can host an application that's useful to some other computer. You might not think of your laptop as a "host," but you're likely running some service that's useful to you, your mobile, or some other computer.

- Local: The local computer is the one you or some software is using. Every computer refers to itself as

localhost, for example. - Remote: A remote computer is one you're not physically in front of nor physically using. It's a computer in a remote location.

Now that the terminology is settled, you can begin.

Activate SSH on each host

For two computers to be connected over SSH, each host must have SSH installed. SSH has two components: the command you use on your local machine to start a connection, and a server to accept incoming connection requests. Some computers come with one or both parts of SSH already installed. The commands vary, depending on your system, to verify whether you have both the command and the server installed, so the easiest method is to look for the relevant configuration files:

$ file /etc/ssh/ssh_config

/etc/ssh/ssh_config: ASCII textShould this return a No such file or directory error, then you don't have the SSH command installed.

Do a similar check for the SSH service (note the d in the filename):

$ file /etc/ssh/sshd_config

/etc/ssh/sshd_config: ASCII textInstall one or the other, as needed:

$ sudo dnf install openssh-clients openssh-serverOn the remote computer, enable the SSH service with systemd:

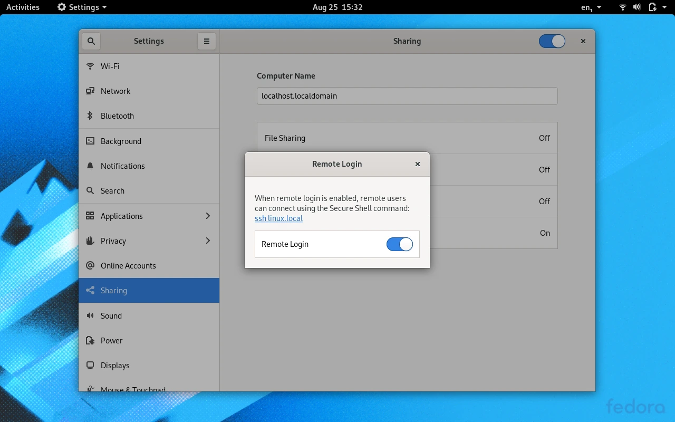

$ sudo systemctl enable --now sshdAlternately, you can enable the SSH service from within System Settings on GNOME or System Preferences on macOS. On the GNOME desktop, it's located in the Sharing panel:

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Start a secure shell

Now that you've installed and enabled SSH on the remote computer, you can try logging in with a password as a test. To access the remote computer, you must have a user account and a password.

Your remote user doesn't have to be the same as your local user. You can log in as any user on the remote machine as long as you have that user's password. For instance, I'm sethkenlon on my work computer, but I'm seth on my personal computer. If I'm on my personal computer (making it my current local machine) and I want to SSH into my work computer, I can do that by identifying myself as sethkenlon and using my work password.

To SSH into the remote computer, you must know its internet protocol (IP) address or its resolvable hostname. To find the remote machine's IP address, use the ip command (on the remote computer):

$ ip addr show | grep "inet "

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

inet 10.1.1.5/27 brd 10.1.1.31 [...]If the remote computer doesn't have the ip command, try ifconfig instead (or even ipconfig on Windows).

The address 127.0.0.1 is a special one and is, in fact, the address of localhost. It's a "loopback" address, which your system uses to reach itself. That's not useful when logging into a remote machine, so in this example, the remote computer's correct IP address is 10.1.1.5. In real life, I would know that because my local network uses the 10.1.1.0 subnet. If the remote computer is on a different network, then the IP address could be nearly anything (never 127.0.0.1, though), and some special routing is probably necessary to reach it through various firewalls. Assume your remote computer is on the same network, but if you're interested in reaching computers more remote than your own network, read my article about opening ports in your firewall.

If you can ping the remote machine by its IP address or its hostname, and have a login account on it, then you can SSH into it:

$ ping -c1 10.1.1.5

PING 10.1.1.5 (10.1.1.5) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from 10.1.1.5: icmp_seq=1 ttl=64 time=4.66 ms

$ ping -c1 akiton.local

PING 10.1.1.5 (10.1.1.5) 56(84) bytes of data.That's a success. Now use SSH to log in:

$ whoami

seth

$ ssh sethkenlon@10.1.1.5

bash$ whoami

sethkenlonThe test login works, so now you're ready to activate passwordless login.

Create an SSH key

To log in securely to another computer without a password, you must have an SSH key. You may already have an SSH key, but it doesn't hurt to create a new one. An SSH key begins its life on your local machine. It consists of two components: a private key, which you never share with anyone or anything, and a public one, which you copy onto any remote machine you want to have passwordless access to.

Some people create one SSH key and use it for everything from remote logins to GitLab authentication. However, I use different keys for different groups of tasks. For instance, I use one key at home to authenticate to local machines, a different key to authenticate to web servers I maintain, a separate one for Git hosts, another for Git repositories I host, and so on. In this example, I'll create a unique key to use on computers within my local area network.

To create a new SSH key, use the ssh-keygen command:

$ ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -f ~/.ssh/lanThe -t option stands for type and ensures that the encryption used for the key is higher than the default. The -f option stands for file and sets the key's file name and location. You'll be prompted to create a password for your SSH key. You should create a password for the key. This means you'll have to enter a password when using the key, but that password remains local and isn't transmitted across the network. After running this command, you're left with an SSH private key called lan and an SSH public key called lan.pub.

To get the public key over to your remote machine, use the ssh-copy-id. For this to work, you must verify that you have SSH access to the remote machine. If you can't log into the remote host with a password, you can't set up passwordless login either:

$ ssh-copy-id -i ~/.ssh/lan.pub sethkenlon@10.1.1.5During this process, you'll be prompted for your login password on the remote host.

Upon success, try logging in again, but this time using the -i option to point the SSH command to the appropriate key (lan, in this example):

$ ssh -i ~/.ssh/lan sethkenlon@10.1.1.5

bash$ whoami

sethkenlonRepeat this process for all computers on your network, and you'll be able to wander through each host without ever thinking about passwords again. In fact, once you have passwordless authentication set up, you can edit the /etc/ssh/sshd_config file to disallow password authentication. This prevents anyone from using SSH to authenticate to a computer unless they have your private key. To do this, open /etc/ssh/sshd_config in a text editor with sudo permissions and search for the string PasswordAuthentication. Change the default line to this:

PasswordAuthentication noSave it and restart the SSH server (or just reboot):

$ sudo systemctl restart sshd && echo "OK"

OK

$Using SSH every day

OpenSSH changes your view of computing. No longer are you bound to just the computer in front of you. With SSH, you have access to any computer in your house, or servers you have accounts on, and even mobile and Internet of Things devices. Unlocking the power of SSH also unlocks the power of the Linux terminal. If you're not using SSH every day, start now. Get comfortable with it, collect some keys, live more securely, and expand your world.

10 Comments