In the last article in this series about home automation, I started digging into Home Assistant. I set up a Zigbee integration with a Sonoff Zigbee Bridge and installed a few add-ons, including Node-RED, File Editor, Mosquitto broker, and Samba. I wrapped up by walking through Node-RED's configuration, which I will use heavily later on in this series. The four articles before that one discussed what Home Assistant is, why you may want local control, some of the communication protocols for smart home components, and how to install Home Assistant in a virtual machine (VM) using libvirt.

In this sixth article, I'll walk through the YAML configuration files. This is largely unnecessary if you are just using the integrations supported in the user interface (UI). However, there are times, particularly if you are pulling in custom sensor data, where you have to get your hands dirty with the configuration files.

Let's dive in.

Examine the configuration files

There are several potential configuration files you will want to investigate. Although everything I am about to show you can be done in the main configuration.yaml file, it can help to split your configuration into dedicated files, especially with large installations.

Below I will walk through how I configure my system. For my custom sensors, I use the ESP8266 chipset, which is very maker-friendly. I primarily use Tasmota for my custom firmware, but I also have some components running ESPHome. Configuring firmware is outside the scope of this article. For now, I will assume you set up your devices with some custom firmware (or you wrote your own with Arduino IDE ).

The /config/configuration.yaml file

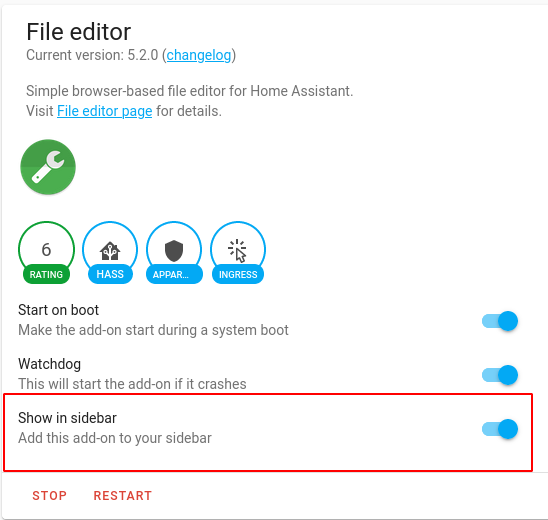

Configuration.yaml is the main file Home Assistant reads. For the following, use the File Editor you installed in the previous article. If you do not see File Editor in the left sidebar, enable it by going back into the Supervisor settings and clicking on File Editor. You should see a screen like this:

(Steve Ovens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Make sure Show in sidebar is toggled on. I also always toggle on the Watchdog setting for any add-ons I use frequently.

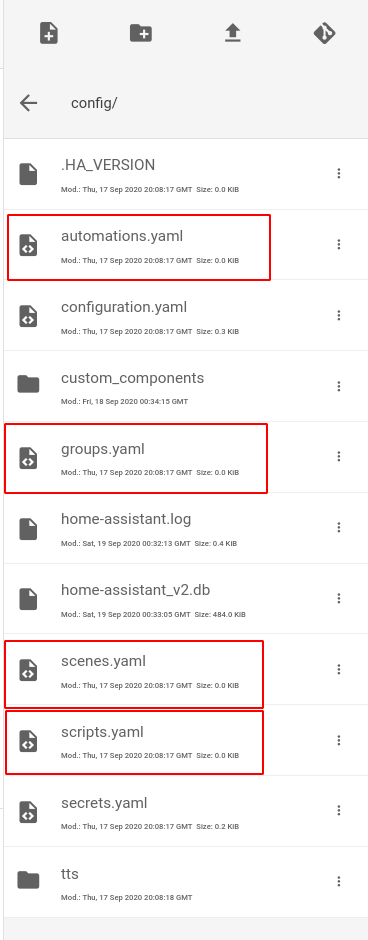

Once that is completed, launch File Editor. There is a folder icon in the top-left header bar. This is the navigation icon. The /config folder is where the configuration files you are concerned with are stored. If you click on the folder icon, you will see a few important files:

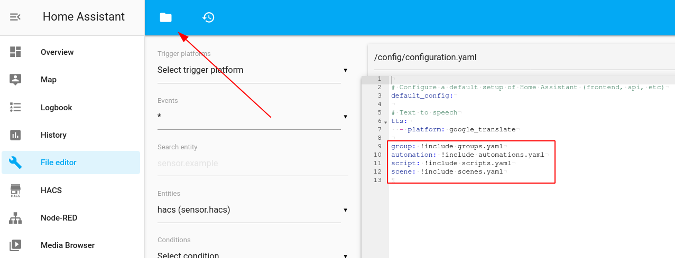

The following is a default configuration.yaml:

(Steve Ovens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The notation script: !include scripts.yaml indicates that Home Assistant should reference the contents of scripts.yaml anytime it needs the definition of a script object. You'll notice that each of these files correlates to files observed when the folder icon is clicked.

I added three lines to my configuration.yaml:

input_boolean: !include input_boolean.yaml

binary_sensor: !include binary_sensor.yaml

sensor: !include sensor.yamlAs a quick aside, I configured my MQTT settings (see Home Assistant's MQTT documentation for more details) in the configuration.yaml file:

mqtt:

discovery: true

discovery_prefix: homeassistant

broker: 192.168.11.11

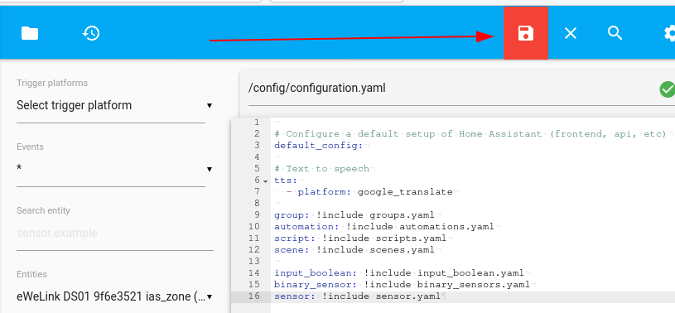

username: mqtt

password: superpasswordIf you make an edit, don't forget to click on the Disk icon to save your work.

(Steve Ovens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

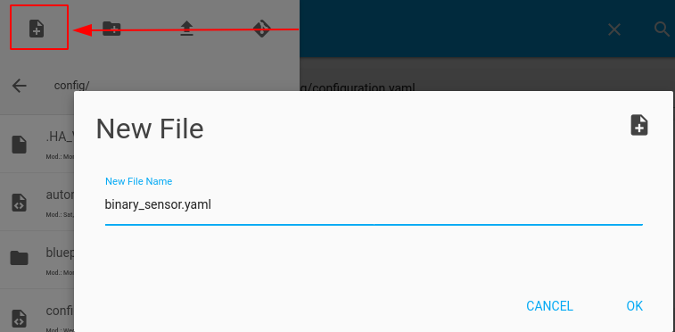

The /config/binary_sensor.yaml file

After you name your file in configuration.yaml, you'll have to create it. In the File Editor, click on the folder icon again. There is a small icon of a piece of paper with a + sign in its center. Click on it to bring up this dialog:

(Steve Ovens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

I have three main types of binary sensors: door, motion, and power. A binary sensor has only two states: on or off. All my binary sensors send their data to MQTT. See my article on cloud vs. local control for more information about MQTT.

My binary_sensor.yaml file looks like this:

- platform: mqtt

state_topic: "BRMotion/state/PIR1"

name: "BRMotion"

qos: 1

payload_on: "ON"

payload_off: "OFF"

device_class: motion

- platform: mqtt

state_topic: "IRBlaster/state/PROJECTOR"

name: "ProjectorStatus"

qos: 1

payload_on: "ON"

payload_off: "OFF"

device_class: power

- platform: mqtt

state_topic: "MainHallway/state/DOOR"

name: "FrontDoor"

qos: 1

payload_on: "open"

payload_off: "closed"

device_class: doorTake a look at the definitions. Since platform is self-explanatory, start with state_topic.

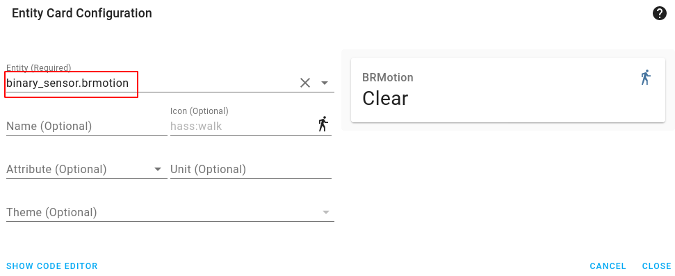

state_topic, as the name implies, is the topic where the device's state is published. This means anyone subscribed to the topic will be notified any time the state changes. This path is completely arbitrary, so you can name it anything you like. I tend to use the conventionlocation/state/object, as this makes sense for me. I want to be able to reference all devices in a location, and for me, this layout is the easiest to remember. Grouping by device type is also a valid organizational layout.nameis the string used to reference the device inside Home Assistant. It is normally referenced bytype.name, as seen in this card in the Home Assistant Lovelace interface:

(Steve Ovens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

qos, short for quality of service, refers to how an MQTT client communicates with the broker when posting to a topic.payload_onandpayload_offare determined by the firmware. These sections tell Home Assistant what text the device will send to indicate its current state.device_class:There are multiple possibilities for a device class. Refer to the Home Assistant documentation for more information and a description of each type available.

The /config/sensor.yaml file

This file differs from binary_sensor.yaml in one very important way: The sensors within this configuration file can have vastly different data inside their payloads. Take a look at one of the more tricky bits of sensor data, temperature.

Here is the definition for my DHT temperature sensor:

- platform: mqtt

state_topic: "Steve_Desk_Sensor/tele/SENSOR"

name: "Steve Desk Temperature"

value_template: '{{ value_json.DHT11.Temperature }}'

- platform: mqtt

state_topic: "Steve_Desk_Sensor/tele/SENSOR"

name: "Steve Desk Humidity"

value_template: '{{ value_json.DHT11.Humidity }}'You'll notice two things right from the start. First, there are two definitions for the same state_topic. This is because this sensor publishes three different statistics.

Second, there is a new definition of value_template. Most sensors, whether custom or not, send their data inside a JSON payload. The template tells Home Assistant where the important information is in the JSON file. The following shows the raw JSON coming from my homemade sensor. (I used the program jq to make the JSON more readable.)

{

"Time": "2020-12-23T16:59:11",

"DHT11": {

"Temperature": 24.8,

"Humidity": 32.4,

"DewPoint": 7.1

},

"BH1750": {

"Illuminance": 24

},

"TempUnit": "C"

}There are a few things to note here. First, as the sensor data is stored in a time-based data store, every reading has a Time entry. Second, there are two different sensors attached to this output. This is because I have both a DHT11 temperature sensor and a BH1750 light sensor attached to the same ESP8266 chip. Finally, my temperature is reported in Celsius.

Hopefully, the Home Assistant definitions will make a little more sense now. value_json is just a standard name given to any JSON object ingested by Home Assistant. The format of the value_template is value_json.<component>.<data point>.

For example, to retrieve the dewpoint:

value_template: '{{ value_json.DHT11.DewPoint}}'While you can dump this information to a file from within Home Assistant, I use Tasmota's Console to see the data it is publishing. (If you want me to do an article on Tasmota, please let me know in the comments below.)

As a side note, I also keep tabs on my local Home Assistant resource usage. To do so, I put this in my sensor.yaml file:

- platform: systemmonitor

resources:

- type: disk_use_percent

arg: /

- type: memory_free

- type: memory_use

- type: processor_useWhile this is technically not a sensor, I put it here, as I think of it as a data sensor. For more information, see the Home Assistant's system monitoring documentation.

The /config/input_boolean file

This last section is pretty easy to set up, and I use it for a wide variety of applications. An input boolean is used to track the status of something. It's either on or off, home or away, etc. I use these quite extensively in my automations.

My definitions are:

steve_home:

name: steve

steve_in_bed:

name: 'steve in bed'

guest_home:

kitchen_override:

name: kitchen

kitchen_fan_override:

name: kitchen_fan

laundryroom_override:

name: laundryroom

bathroom_override:

name: bathroom

hallway_override:

name: hallway

livingroom_override:

name: livingroom

ensuite_bathroom_override:

name: ensuite_bathroom

steve_desk_light_override:

name: steve_desk_light

projector_led_override:

name: projector_led

project_power_status:

name: 'Projector Power Status'

tv_power_status:

name: 'TV Power Status'

bed_time:

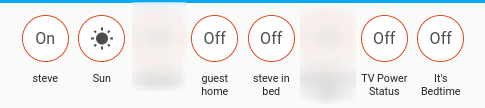

name: "It's Bedtime"I use some of these directly in the Lovelace UI. I create little badges that I put at the top of each of the pages I have in the UI:

(Steve Ovens, CC BY-SA 4.0)

These can be used to determine whether I am home, if a guest is in my house, and so on. Clicking on one of these badges allows me to toggle the boolean, and this object can be read by automations to make decisions about how the “smart devices” react to a person's presence (if at all). I'll revisit the booleans in a future article when I examine Node-RED in more detail.

Wrapping up

In this article, I looked at the YAML configuration files and added a few custom sensors into the mix. You are well on the way to getting some functioning automation with Home Assistant and Node-RED. In the next article, I'll dive into some basic Node-RED flows and introduce some basic automations.

Stick around; I've got plenty more to cover, and as always, leave a comment below if you would like me to examine something specific. If I can, I'll be sure to incorporate the answers to your questions into future articles.

2 Comments