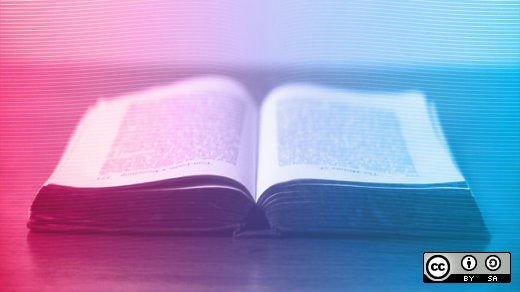

One of my favorite shelves at my local comic book store is the zine rack. Filled with self-published booklets that are too niche, too quirky, or just too individual for any company to spend money on producing, zines are produced by one or two people who have something to say and want to express themselves through text and graphics. Zines are usually created by cutting out blocks of text and graphics and literally pasting them to a master page. Once everything has been laid out, each page is scanned and printed on a copy machine, and distributed to comic book stores, used book stores, Infoshops, and libraries. When you're a computer nerd like me, though, you have easier access to a computer than you do scissors and glue, and my first choice for desktop publishing with open source is Scribus.

Desktop publishing

There are different tools for different jobs, but there can be a lot of overlap. You can produce books for online distribution as a comic book archive or djvu file, Epub, or even good old HTML. However, if you're producing a book for print, then at least one of your targets must be PDF (or at least Postscript) because that's what printers use. When I'm working on something with more graphics than typed content, or I just need maximum flexibility for layout, I use Scribus because its canvas is freeform, and it can link to external assets rather than import them.

Image layout

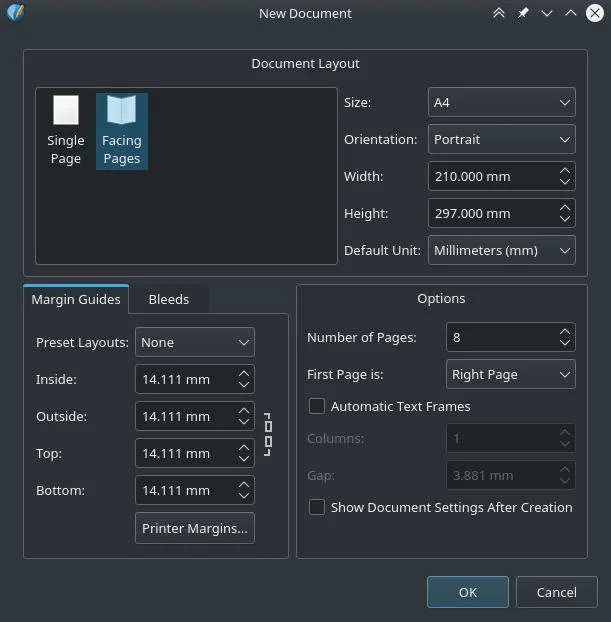

When you launch Scribus, you're asked to choose a medium to work with. By default, a project starts with a portrait-oriented Letter or A4 page, depending on your region. You can also set your margins here, the number of pages you'd like to start with, and whether you want to design on a single page or two facing pages. When designing for facing pages, you usually want the first page to be a right page (take a book off your shelf and spread it open, face down to see that the front cover is the right half of a wide page).

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

You can always add more pages to your project later, but the page size is an important decision because it's what your layout is based on. While you can change the page size later, adjusting your layout for the new page dimensions takes work, so plan ahead.

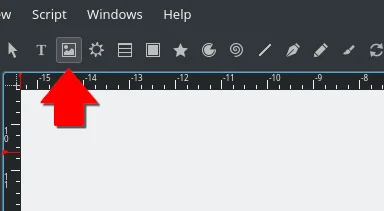

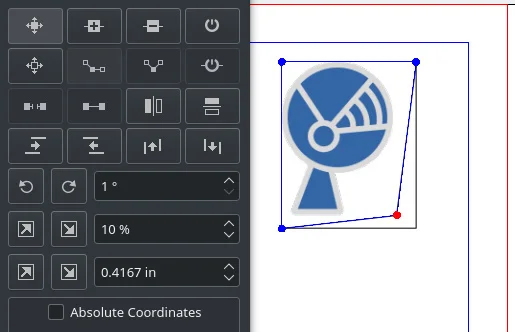

You can very broadly think of page layout as organizing two elements: text and images. For many projects, the first page is the easiest because it often contains just one big graphic: the front cover. To add an image to a page, click the Image Frame icon (or press I on your keyboard).

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

With the Image Frame tool active, click and drag to create a frame for the graphic you want to insert into your document. The term frame doesn't mean there will actually be a picture frame around your graphic; it's just the term Scribus uses to indicate that you're creating space in which an image will be visible. Once you've drawn the frame representing where your image is meant to appear, right-click on it, select the Content menu, and choose Get Image (or just double-click on the frame, or press Ctrl+I on your keyboard). Choose the image you want to add to the frame.

An alternate method to this process is to just drag-and-drop an image from your file manager onto a Scribus page. Scribus links to the image and creates a frame for you. I consider this sublimely simple method an "alternate" method because when I'm doing page layout, it's rare that all the graphics I want to add are perfectly sized for my intended layout. Adding the frames manually provides me with greater flexibility upfront. However, you can adjust image frames and image sizes at any point during layout, so use whatever method is easiest and most natural for you.

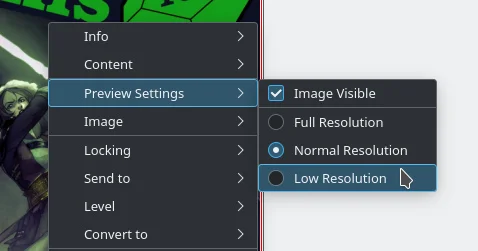

Image previews

Here is an important feature of Scribus: it doesn't import graphics into your document; it only points to those graphics on your hard drive. The benefit is that you can have page after page of huge graphics in your book, but your Scribus file hardly grows at all. You can also adjust how Scribus displays the images while you work. Sometimes, when I'm concentrating on copy, I turn off image previews entirely, so I don't ever have to wait for graphics to render.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

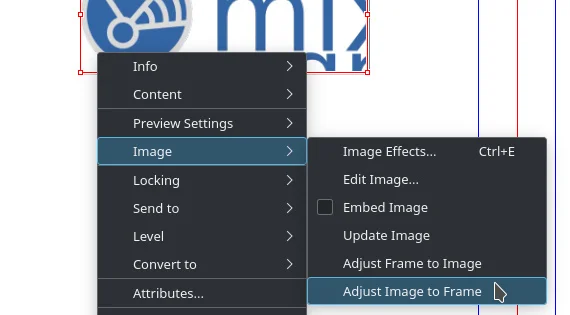

Image and frame size

In the physical world, a page only has so much space on it, and sometimes the images you're trying to fit know no bounds. You can resize images to fit, though, either by shrinking the image in Scribus or by cropping or masking the image.

To resize an image, draw an image frame to fit the space allotted. Press Ctrl+I to add your image as usual. When the image is too large for its frame, you see just the top left of the image, as if you were looking in on the image through a window frame. Right-click on the image and find the Image submenu. Select Resize Image to Frame to adjust the image to fit into the bounds of your frame.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Not all images fit neatly into a rectangle box, though, so sometimes making an image fit means changing the frame altogether. To edit a frame, go to the Window menu and enable the Properties panel (or press F2 on your keyboard). In the properties panel that appears, find the Shape section. The default shape of all frames is a rectangle. There are lots of shapes to choose from, though, so browse through your options by clicking the rectangle button to the right of the Shape setting. Should you prefer to define your own custom shape, click the Edit button and do whatever you need to do to make your image look like it belongs on the page.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Text frames

Adding text to Scribus is surprisingly similar to adding graphics. You draw a frame, import your text, and then manage the shape of the frame as your layout demands.

To add text, click the Text Frame button in the top toolbar or press T on your keyboard. Click and drag to define the region for your text to appear. Scribus doesn't assume that you will manually type your text into the text frame because, in some workflows, a copy editor manages the text (called "copy" in the publishing industry) well before layout begins. To import text from a separate file, right-click the text frame, find the Content submenu, and choose Get Text (or just press Ctrl+I on your keyboard).

Alternately, you can double-click the text frame to add or edit text manually.

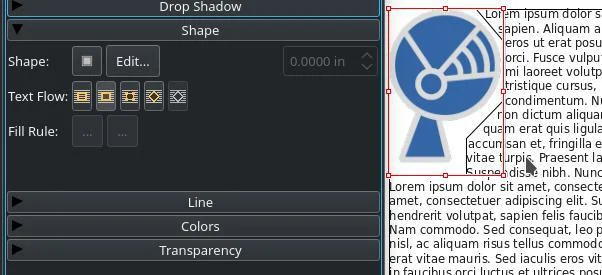

Text wrap

The same options for adjusting image frames are available for adjusting the size and shape of your text frame, with the addition of smart text flow (also known as "text wrap" in some applications). When you want text to flow around an image, select the image frame and navigate to the Shape properties panel. In the Shape panel, choose how you want the image and your text to interact.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

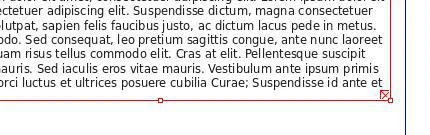

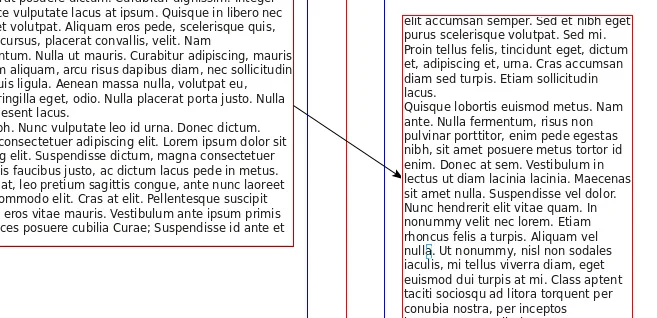

Linking text frames

Text is just another graphical element to the layout artist, so text frames are bound to each page. But text isn't usually written by the page, so it's common for one block of text to span more than one page. By default, when text overflows its frame, you get a red warning box in the lower right corner of the text frame.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

To allow text to flow from one frame into another, you can link frames together. To link text frames, select the frame containing the overflow, and then click the Link Text Frames button in the top toolbar (or press N on your keyboard).

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

With Link Text Frames active, click the text frame you want the text to flow into.

(Seth Kenlon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

You can do this across as many pages as you require, and you can unlink them using the Unlink Text Frames (or U on your keyboard) button at any time.

Install Scribus on Linux

Scribus is available on most Linux distributions from your package manager. On Fedora, Mageia, and similar distributions:

$ sudo dnf install scribusOn Elementary, Mint, and other Debian-based distributions:

$ sudo apt install scribusHowever, I use Scribus as a Flatpak.

Professional layout for open source

Scribus is a professional-grade layout application, and this introductory article hardly does it justice. One feature I particularly appreciate is the Page menu's options to snap to guides, snap to grid, and snap to nearby items. This feature makes quick layouts possible and eliminates the need to refer back to page and item measurement constantly. Scribus exports to PDF and many other formats and produces print-ready documents for printing either at home, office, or professional print shop.

5 Comments