The jury verdict last Friday in favor of Red Hat and Novell in a case based on bad software patents owned by "non-practicing entities" is an important victory for the open source community. Those in the business of acquiring bad software patents to coerce payments or bring lawsuits should be worried. Two such businesses were plaintiffs in our case, and they did their best to confuse the jury in one of their favorite locales, eastern Texas. But it didn't work. The jury unanimously found that the patents were not infringed, and, even worse for the plaintiffs, that the patents were invalid.

The case was about allegations by IP Innovation, L.L.C. (a subsidiary of Acacia Technologies), along with Technology Licensing Corporation that Red Hat and Novell infringed four claims from U.S. Patents 5,072,412, 5,394,521, and 5,533,183. The patents share a common disclosure and are all titled “User interface with multiple workspaces for sharing display system objects.” The patents relate to a computer-implemented system and method for providing a graphical user interface with multiple workspaces.

Like most patent cases, this one involved technical subject matter and terminology. However, the plaintiffs came forward with minimal evidence to support their argument of infringement. They also faced abundant evidence showing that the patents were invalid based on prior art. In other words, there was nothing new in these “inventions” sufficient for a patent.

In these circumstances, you might suppose that a rational patent plaintiff would dismiss the case, perhaps in return for a token payment. Instead, the plaintiffs decided to ask the jury for millions of dollars. Their theory appeared to be that the jury might be confused by the technical terms and unsympathetic to out-of-state businesses with creative business models.

With that end apparently in view, the plaintiffs' counsel launched an attack on the theory and practice of open source software. It was clear during jury selection that our jurors had no prior knowledge of, or experience with, open source. Plaintiffs attempted to exploit this inexperience by arguing that open source software involved behavior that was, if not downright illegal, at least ethically dubious. They promoted the fallacy that open source distributors unfairly take the property of others and thereby unfairly profit. They also suggested that Red Hat's public criticisms of the U.S. patent system as it relates to software and related calls for legal reform were un-American and indicated a secret fondness for the writings of Karl Marx. I kid you not! As absurd as this argument sounds, after many hours of sitting on a hard courtroom bench, I briefly wondered whether the jury might fall for this version of the classic FUD strategy and be so fearful and confused as to find for the plaintiffs.

It turned out that there was no cause for concern. Michael Tiemann, Red Hat's vice president of open source affairs, explained the fundamentals of open source so as to make them clear, and even inspiring. He explained that open source software is about voluntary collaboration, not involuntary expropriation. He also made plain that Red Hat's legitimate criticisms of the existing patent system in no way shows a proclivity to infringe patents or indifference to patent claims, and that Red Hat respects and abides by the law.

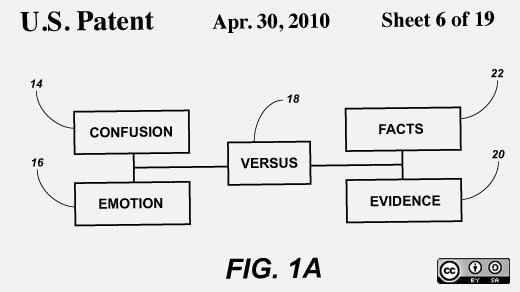

Our side took the opposite approach from the plaintiffs, basing our case on facts and evidence, rather than emotion and confusion. Our experts carefully showed that our products were noninfringing and demonstrated specific examples of prior art. In the end, the jury saw through and quickly rejected plaintiffs' FUD. The jurors took a bit more than two hours to find every one of 23 issues in favor of Red Hat and Novell.

We learned many things from this experience, but I'll note just three here. We now know for certain that those in the business of bringing software patent lawsuits are not invincible, even in the supposedly patent-friendly jurisdiction of the Eastern District of Texas. We know that Texas juries are willing to reject bogus infringement claims and invalidate bad software patents. And we know that attacks on open source based on FUD will not stand up when subjected to the light of truth.

81 Comments