When well-known, richly compensated patent lawyers switch from representing world-class tech companies to servicing "non-practicing entities," something's up. Could the sordidness of a business based on bringing patent lawsuits be outweighed by large amounts of cash? At least for some, apparently yes.

This week Ashby Jones wrote for the Wall Street Journal about two specific patent lawyers, John Desmarais and Matt Powers, as representative of a larger shift in the practice. Each of them was once an attorney for large companies, protecting those companies' patent interests in court. Desmarais' software-related clients included IBM and Verizon; Powers has represented Cisco, Oracle, Microsoft, and Apple. But today they have joined the ranks of "patent trolls," the colloquial term for "non-practicing entities" (NPE), which exist only to pursue the monetary benefits of aggressive patent-infringement lawsuits.

Ideally, patents protect and motivate innovation as well as benefit future innovators. They can be an important business justification in fields where R&D is expensive, like pharmaceuticals. They put the details of an innovation into public view, inspiring improvements and making a record of its existence, both for historic record and the benefit of future inventors. Thus, companies once used patents to protect what they had put significant resources into creating. Likewise, patent lawyers would work for those companies to defend their patents. Now there are those who are interested only in the financial gain and not in protecting innovation--like Desmarais and Powers.

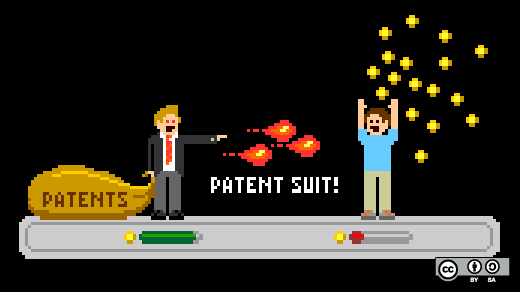

But this approach is contrary to the intent of the patent system. Worse is when, as the WSJ highlights, some companies sell their patents to an NPE to prevent them from being in the awkward position of suing customers or partners. This practice puts the patent's advantages in the hands of a non-creator, who almost certainly does not hope to inspire, much less be responsible for, future innovation. Instead of benefiting innovators and the public, going on the patent offense benefits only the bank accounts of the trolls.

And that's precisely how and why Desmarais switched from helping companies to founding an NPE. Micron Technology offered him the purchase of 4,200 patents. "I didn't bite at it right away, but it didn't take me long to realize that this was a rare and unique opportunity," Desmarais is quoted in the story. He took the patent portfolio and founded Round Rock Research, resigning from his prior position. With them, he has achieved licensing deals from myriad tech companies, including IBM, which he once defended. And how is it working out? Quite profitably--for Desmarais. Detrimentally to the technology industry.

It's a dangerous shift with potential great harm to software innovation when some of the most valued attorneys switch from defending hard-earned creations to pursuing their previous bosses for profit. Ashby concludes by noting that NPEs aren't likely to be restricted by the courts anytime soon, which may make side-switching lawyers like these a disturbingly common occurrence.

Read the Wall Street Journal story (subscription required).

3 Comments