Editor's note: This article is part of a series on working with mental health conditions. It details the author's personal experiences and is not meant to convey professional medical advice or guidance.

Something in a recent podcast interview with food writer Melissa Clark caught my ear. Asked if she was a "productive person,'' Clark replied by saying: "I am an anxious person. I have a lot of anxiety, and my way of coping with it is to be very, very busy […]. That's how I deal with the world. I [pause] do."

Clark's point resonated with me, because I live with multiple mental health conditions that have a fundamental impact on how I approach my work. And I believe they've played a role in the career success I've experienced.

I have generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Both of these conditions have had serious impacts on my life. Some of those impacts have been disruptive. At the same time, some have contributed positively to my success and my development as a leader in a growing organization.

I've spent most of my career in an organization built on openness and transparency, and yet I have rarely spoken about my mental health and how it might impact my work. In sharing these stories now, I hope to help reduce the stigma of mental health at work and connect with others who may be experiencing similar or related situations. Given the prevalence of mental illness globally, chances are good that if you don't experience a mental health condition first hand, then you're likely working on a daily basis with someone who does.

Learning about how mental illness manifests at work may help you navigate relationships with others as well as your own challenges. As a leader in an open organization, I feel compelled to share my experiences in the hope that they are useful to others. Working openly has specific implications for me—and, I suspect, for others with similar mental health conditions—which I'll detail in this series.

How it started

My anxiety and OCD started shortly after I graduated from college and was living in New York City (though I could probably trace their histories further, this was the moment when they became apparent). The wave of confidence I rode during the dot com boom was crushed in the bubble-bursting crash in March of 2001. The memory of coming into work, being called into an all hands meeting (the first we'd ever had at my small company), and being told that as of today there was no money to make payroll, is etched into my mind.

My girlfriend and I had just moved into a $2100-per-month apartment. Fear of not being able to pay the rent, or being otherwise swallowed up by the city, resulted in a general sense of unease and nervousness in my gut, combined with very real symptoms of OCD.

For example, while walking to work at a temp job I took after my company folded, I would wonder if I had remembered to lock the apartment door. I would retrace the steps of my morning routine in my mind, trying to find that moment when I turned the key. If I couldn't specifically remember, the sense of unease and worry in my gut would build to the point that I couldn't think about anything else. Frequently, I would turn around, rush back home, and double check that the door was locked. When I did so, I would have to do something memorable, like repeat a phrase out loud, so that I could mark the moment in my memory. Then, back on the way to work, I would again wonder if I had locked the door, and I could say "Yes, and when you did it, you said out loud 'It's Tuesday morning and I'm locking the door!'"

So, how does this translate to an advantage at work?

One of the primary factors contributing to success at my company is an ability to take initiative. Much work needs to be done, and we're in an environment of continual growth and change—which means it's not always clear what needs to be done or who should be doing it. That creates the opportunity for people to observe a need then step up to fill it. This is true in many open organizations, where everyone, regardless of job title or level, is encouraged to step forward.

Living with anxiety, I continually feel like I need to be doing something, or worry that I'm not doing enough. This motivates me to seek opportunities for contributing. In other words, the anxiety makes me proactive. Being "proactive" or a "self starter" is something you'll find in the "qualifications" section of many job postings!

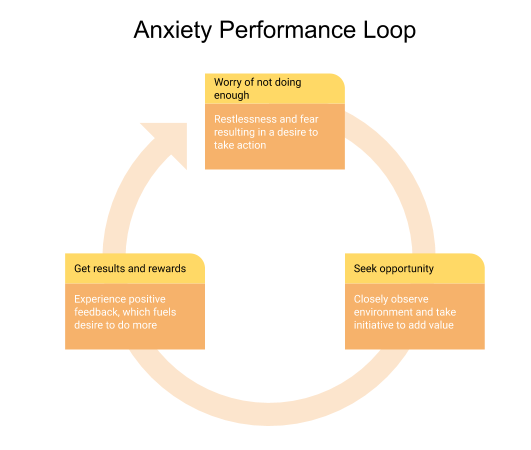

I'm very fortunate to have built my career at a successful company, where continual growth creates financial incentives. One of my largest anxieties is about money—the fear of not having enough of it. Being in a leadership role at a quickly growing, profitable company exponentially multiplies what I call the anxiety performance loop (see Figure 1). A high quarterly bonus or other financial reward for a job well done is an invitation to do more, to raise the bar higher, to double down on the behaviors that seem to provide positive outcomes at work. Quarter after quarter after quarter.

Figure 1: The "anxiety performance loop"

You can observe in all this a virtuous cycle: Opportunities I find at work satisfy my mental needs, and as a result I experience success and rewards. And this, on the face of it, is true.

So, what's the problem?

The anxiety-driven performance loop presents two challenges: it never ends, and it is based on a negative emotional state (fear and worry).

Perhaps the best phrase to illustrate this would be "What have you done for me lately?" In my mental landscape, this is what everyone is thinking about me all the time. No matter what I achieve, no matter what reward or recognition I receive, I imagine that within minutes the person acknowledging my achievement is thinking, "Now, why are you still sitting there? Get out and go do some more!"

People are not, of course, really thinking this. But my mind can locate enough truth in it to justify a quick return to the fear of not doing enough, which restarts the cycle.

We live in a world of short attention spans, high expectations, and significant competitive pressures. All of these are real challenges that fuel the idea that after each accomplishment we need to raise the bar higher and keep going. Having anxiety causes me to internalize these pressures, which triggers the "looping" effect.

The result is that both my company and my career benefit. Mentally, though, I get exhausted.

I have developed a few coping mechanisms to help me maintain balance:

- Meditation. After I was first diagnosed with my conditions almost 20 years ago, I saw a therapist. After a round of sessions, the therapist referred me to a meditation center, which opened up a new world of thought for me. I've recently been working to reinvigorate my daily practice.

- Exercise. I'm a bit compulsive about exercise. I make time every single day for at least one hour of exercise (for me it's walking, cross country skiing, or running).

- Self awareness, reality checks, and reminders. Anxiety and OCD can lead to a distorted view of reality. I may overstate stakes, read too much into other people's motivations, or imagine consequences that are just not realistic. Reminding myself of the true worst case scenario (which usually isn't that bad), realizing that other people have more important things to worry about than me, or reminding myself that this is "just a job" can all help bring me back to a realistic perspective. I also have a few other people who can help with this.

So far I've focused primarily on the performance-enhancing aspects of anxiety. In future articles, I'll discuss some of its performance-reducing aspects, as well as the impact my condition has on my colleagues.

25 Comments