In electrical engineering, a transient fault is defined as an error condition that vanishes after the power is disconnected and restored. This is also a workaround many of us unconsciously use when we forcefully power our physical devices off and on when they're performing poorly or frozen on a blue crash screen filled with gibberish.

In cloud computing, we are faced with increased complexity, known unknowns, or worse, unknown unknowns with infrastructure we will never touch as well as technology that's evolving at an exponential rate and disparate solutions connecting an expanding digital world. Today's virtual users' tolerance for unresponsive, unreliable, and underperforming products is zero—everyone wants 24x7 uptime and solutions that evolve and blend into their lifestyle.

In this new virtual world, we cannot just walk up and reboot a machine, at least not without impacting hundreds, thousands, or even millions of users. And loyalty to brands and products is dwindling fast in today's competitive world; users would probably look for an alternative service at a click of a keystroke and never return rather than put up with any measurable amount of downtime.

Let's take a quick look at two events that were humbling reminders that today's transient faults can occur in a heartbeat, are complex to identify and resolve, and have a profound impact on our stakeholders.

- A Rough Patch: "We've had some issues with the service over the past week and a half. I feel terrible about it, and I can't apologize enough. It's the biggest incident we've had since the instability created by our service refactoring," wrote Microsoft corporate VP of cloud developer services Brian Harry on his blog. After weeks of sleepless nights, the root cause was identified as a storm of requests to the access control service (ACS) that exhausted Source Network Address Translation (SNAT) ports, prevented authentications, and impacted our stakeholders.

- 503 Error: "Setting up monitoring from the beginning of the implementation of our Azure function confirms the importance of monitoring in the DevOps process," reported Cellenza's Mikael Krief on the ALM DevOps Rangers blog. Again, we spent sleepless nights finding the root cause of why our refactored extension spawned a storm of connections and threads, imploded our Azure service, and frustrated our stakeholders with 503 Service Unavailable errors.

We can set up failure and disaster recovery for our cloud applications to help minimize, not eliminate, the impact of an outage caused by resource failures or natural disasters. However, for solutions that use remote resources or communicate with remote services, we need to add a pinch of sensitivity to transient faults. Well-designed solutions detect and attempt to self-correct transient faults before sounding an alarm—or worse, becoming unresponsive and failing.

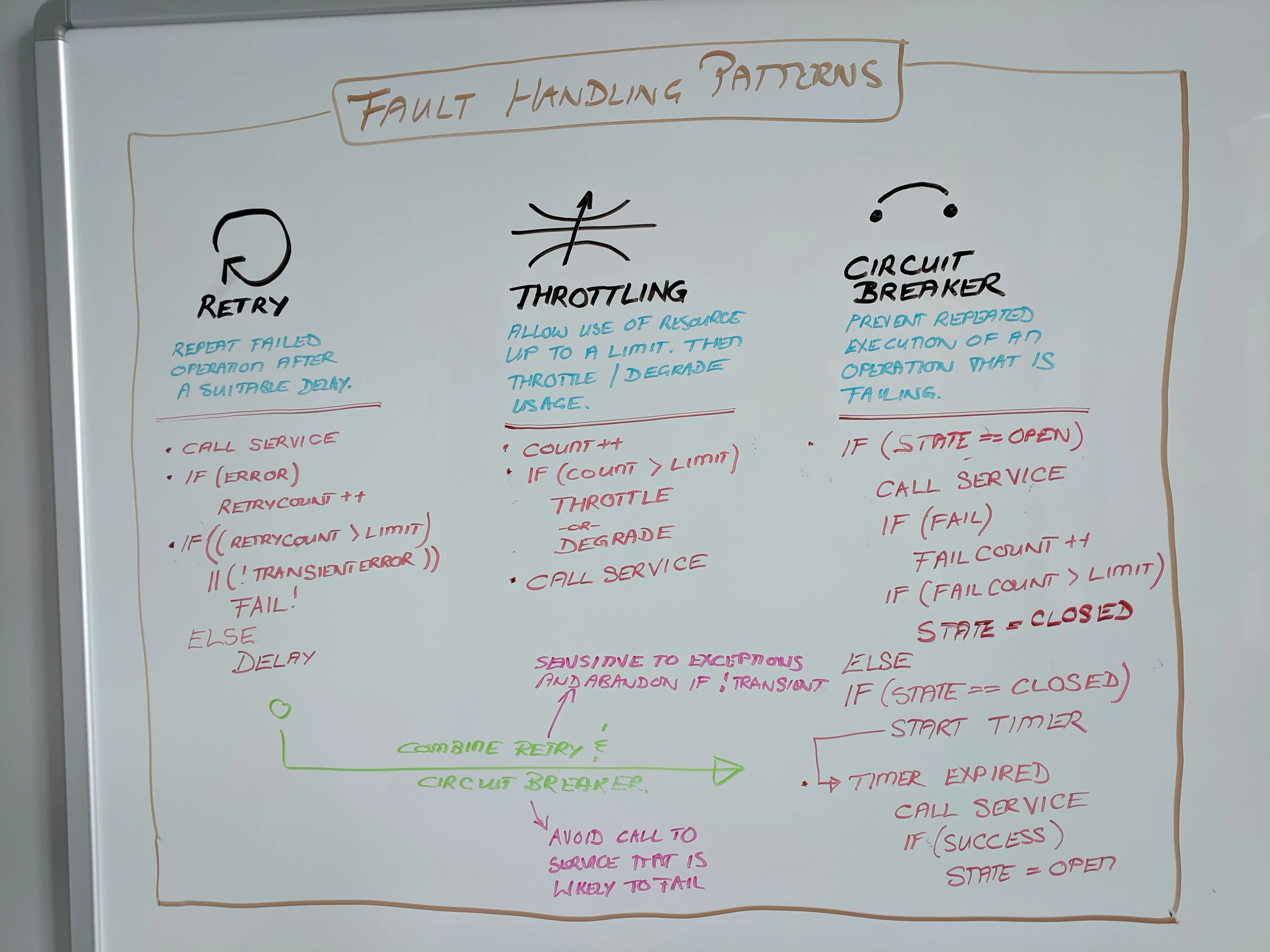

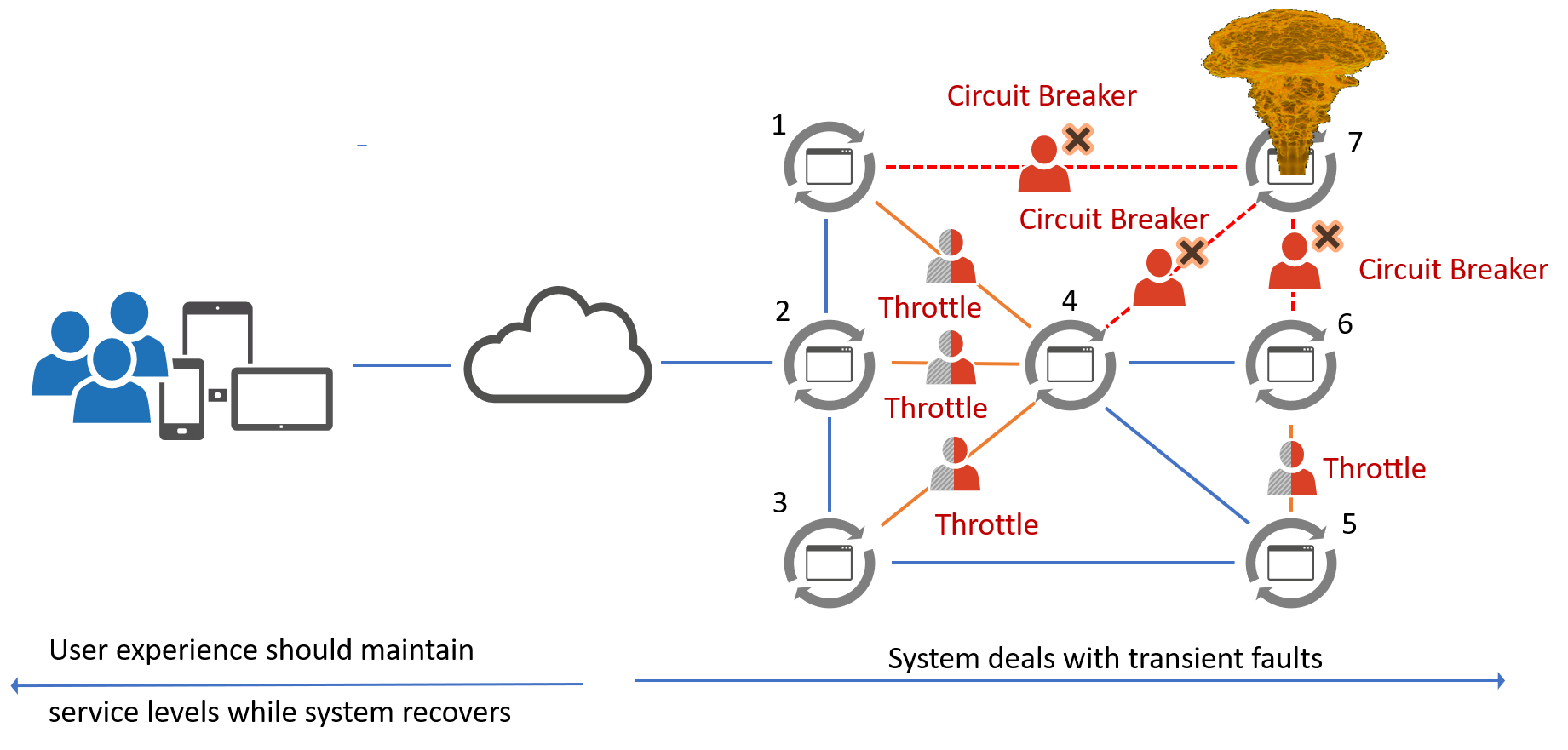

There are a handful of transient fault handling patterns, including the three shown on the following whiteboard: retry, throttling, and circuit breaker.

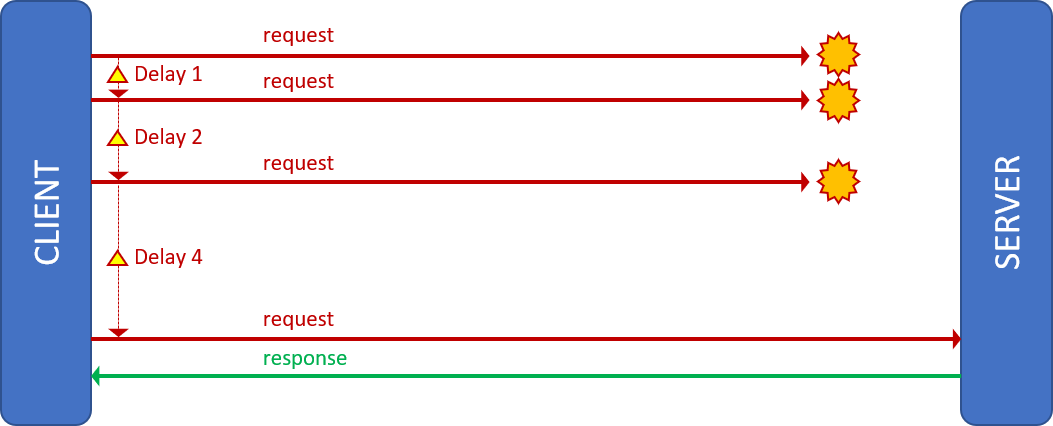

Retry pattern

The retry pattern is the simplest of the three transient fault handling patterns and something we do naturally in everyday life. It can be effective in solutions that communicate across distributed networks to handle transient faults caused by issues such as network latency, service overloads, and power outages.

Pseudocode

Set failure_count = 0

Call the [micro] service

If (fail) failure_count++

If (failure_count > retry_limit) or (not transient failure) FAIL

Delay (delay_time)

Increase delay_time by factor of failure_count

Retry step 2

The pattern ensures that a user's request eventually succeeds during less-than-ideal situations where transient failures would otherwise result in immediate and frequent failures. See open source implementations such as java-design-patterns and transient-fault-handling-application-block for details.

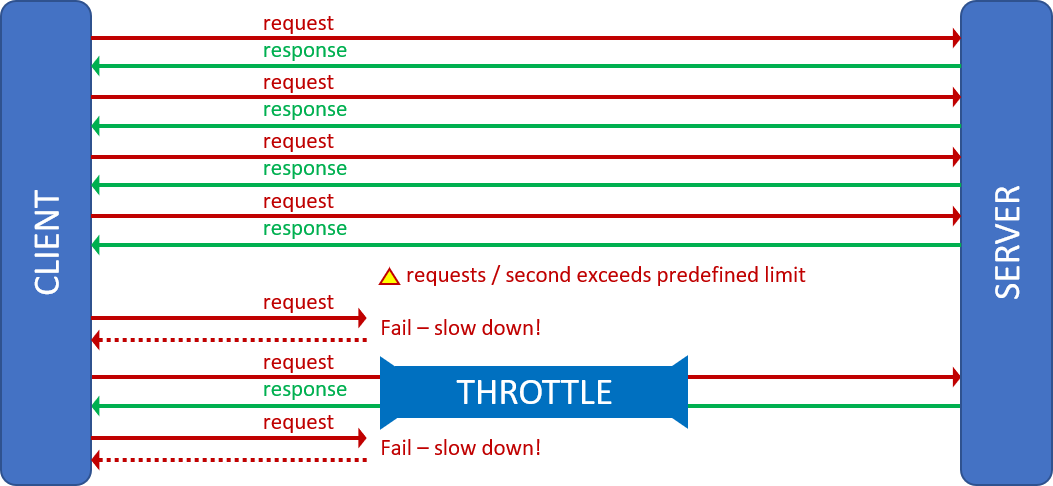

Throttling pattern

We need to protect our services against clients that are overutilizing our solution or have gone rogue due to a system or logic failure. Like a four-lane tunnel servicing a six-lane freeway, we must manage the flow of requests (cars) and throttle endpoints (lanes) that are exceeding the maximum throughput (tunnel).

Pseudocode

Increment request_count

// Limit – Maximum requests within an interval

// Degrade – Fail with “slow down” error or pause operation

If (request_count > limit) degrade service

Call the [micro] service

The pattern helps us meet service level agreements, prevent a single user from overutilizing the system, optimize request flows, and deal with bursts of unexpected requests. One of the reasons we need to increase the delay between retries in the previous pattern is to ensure that we do not inadvertently exceed the throughput of the system and trigger degradation of service. See open source implementations such as WebApiThrottle and Core.Throttling for more details.

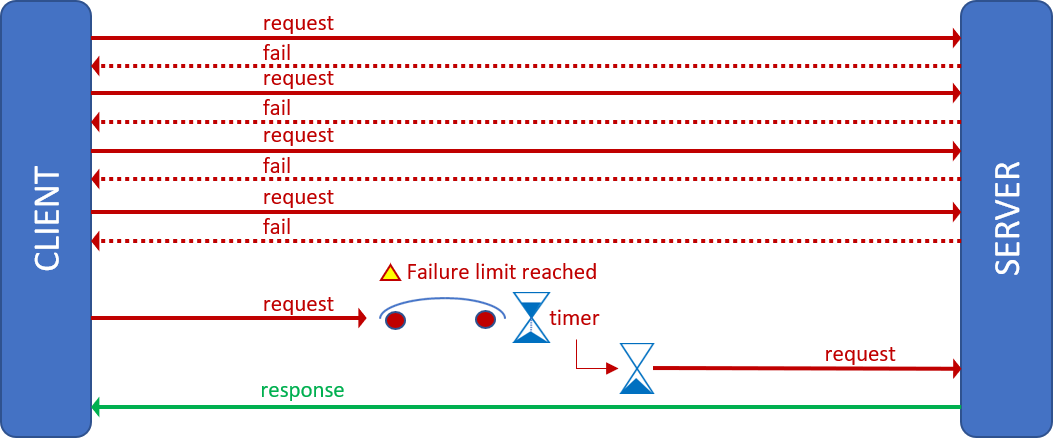

Circuit breaker pattern

Like circuit breakers in your home, the circuit breaker pattern is your last defense. While the retry pattern helps to autocorrect brief transient faults, this pattern is more suited for transient faults that take a longer period to resolve. When dealing with network or service outages, such as the Rough Patch event, retrying a failing service operation could worsen the situation, lead to cascading failures, and eventually trigger a solution meltdown. The hypothesis of the circuit breaker pattern is that the failed service call is likely to succeed if (and only if) it is automatically retried after a significant delay.

Like when you stagger into your basement in the dark to find your circuit breaker cabinet, you are allowing the electrical system and potential static charges to recover before you flip the switch.

Pseudocode

// Circuit breaker has not tripped

If (circuit_state == open)

Call the [micro] service

If (fail) fail_count++

If (fail_count > limit) circuit_state = closed

// Circuit breaker tripped

Else

If (circuit_state == closed) Start Timer

// Call back for timer event

On Timer timeout

Call the [micro] service

If (success) circuit_state == open

See open source implementations such as Hystrix, circuit-breaker, and Polly for more details.

Don't fear faults

Remember to include unit and integration tests for all known faults and implemented handling patterns. Your unit tests must validate that your solution reacts appropriately when your fault-handling logic is triggered. On the other hand, your integration tests must simulate resilient faults to verify that your solution of collective services can deal with the fault effectively. You can simulate services, transient faults, and degrading services by using service virtualization such as Hoverfly. Your stakeholders will not be amused if your solution and associated fault handling patterns fail to deliver the promise of self-healing and avoidance of catastrophic meltdowns.

So, faults, like failures, are a feature in blameless DevOps and we should not fear them. To remain competitive, we must raise the quality bar of our infrastructures, solutions, and accountability to detect, remediate at the root-cause level, and self-correct to maintain an acceptable service level.

For example, in the following illustration, microservice #7 has imploded, triggering circuit breakers and traffic throttling and allowing the system to recover while continuing to service the users. What is evident from this simple illustration is that the combination of faults and the difficulty of dealing with them can become complex at the flip of a switch of a feature flag.

These and other patterns are powerful allies for one of the core values of a healthy DevOps mindset to "improve beyond the limits of today's processes—strive to always innovate and improve beyond repeatable processes and frameworks." They help us raise the quality bar and continuously deliver business value and delight our stakeholders.

Special thanks to Brent Reed for his candid review and feedback that help us improve and share our insights.

2 Comments