Skipper is an open source HTTP router and reverse proxy for service composition. As its GitHub page states, it's designed to handle large amounts of dynamically configured HTTP route definitions (>600,000 routes) with detailed lookup conditions and flexible augmentation of the request flow with filters. It can be used out of the box or extended with custom lookup, filter logic, and configuration sources.

Proxies

When some people think of a proxy, they imagine a webpage that serves as a gateway to an intranet or a suspicious-looking webpage designed to unblock social media sites on a school or work network. A forward proxy is one that operators of desktop infrastructure use to save internet bandwidth, enforce parental controls, or limit social media access. Another kind of proxy is one in which an individual user navigates to a page, provides credentials, and is then forwarded to a protected intranet resource. The inverse of that kind of proxy is the reverse proxy, which accepts all traffic and forwards it to a specific resource, like a server or container. That's the kind of work Skipper does for infrastructure.

When I read Matt Klein's post on modern network load balancing and proxying, I realized that we, as Skipper maintainers, should explain more features and details about why and how you can leverage HTTP proxies. In this article, I will treat the terminology "HTTP (reverse) proxy" and "HTTP router" as the same.

HTTP routing

According to Wikipedia: "Routing is the process of selecting a path for traffic in a network." This definition refers to routing at OSI layer 3, most commonly based on IP with routing protocols like BGP or OSPF. Since this article isn't about one of those, I will try to explain what HTTP routers are about. But first, I want to introduce Skipper, an OSI layer 7 HTTP router library written in Go and a core component of retailer Zalando's e-commerce shop and the Kubernetes Ingress infrastructure.

At Zalando, we use Skipper as a Kubernetes Ingress controller to support our users with visibility, reliability, security, and additional features to offload common applications.

Any organization running HTTP services, often in a microservice architecture, needs to route HTTP requests to the right applications. HTTP routers route based on information provided by the HTTP request. For example, the following shows an HTTP/1.1 request.

GET /details HTTP/1.1

Host: www.zalando.de

User-Agent: curl/7.49.0

Accept: */*

Authorization: Bearer <token>

...We can route based on the method GET, the path /details, the Host header www.zalando.de, or any arbitrary part of the request.

One common problem an application owner faces is splitting an API into multiple applications, so you need to split the responsibility of a component into subcomponents. Another common task is to support refactoring; maybe you have rewritten one part of your app, and you want to deploy it separately now.

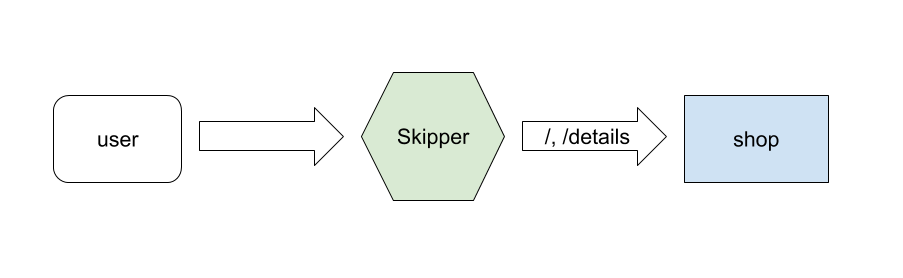

For example, imagine you you have a store that has a list of products and their details, and you need to split it into shop and product backend applications. At /, your shop shows the list of products, and at /details, it shows product details, such as color, size, sustainability, and price.

Figure 1: Shop

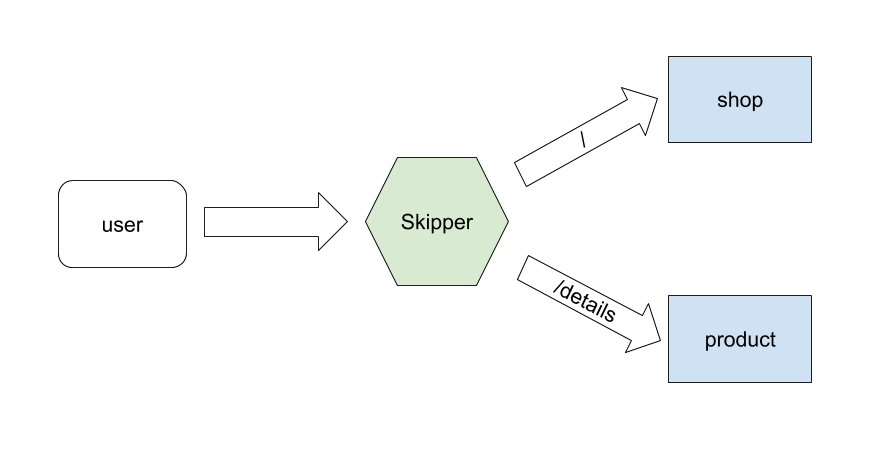

You need to split the responsibility of the product detail into its own application, such that / stays in the shop application and /details is refactored to the product application.

Figure 2: Two backend applications, product and shop

To make sure an HTTP proxy finds the right backend for an incoming request, it uses a routing table to check the destination to make sure it's correct.

Routing tables

In Skipper, the routing table is created by pulling information generated by dataclients from different sources. One source can be a routes file, similar to what you may see in more popular HTTP servers, like Apache or Nginx.

Depending on the size of your organization—or better, the number of backend applications—the routing table can grow quite large. Skipper implements the routing table as a tree that can scale beyond 600,000 routes (far more than you'd want to manage in an Nginx or Apache config).

Following along with the example application above, Table 1 shows the routing table from Figure 2. The store / should be routed to shop, and the /detail routed to the product application.

| path | app |

|---|---|

| / | shop |

| /detail | product |

Table 1: Routing table

The available dataclients in Skipper fetch routes from different sources and what a route consists of.

Dataclient

The routing configuration in Skipper's routes file dataclient is similar to what you might know from HTTP proxies in Nginx or Apache. In Skipper, a routes file specifies all routes in eskip syntax, as shown in Figure 3.

r1: P1() && P2() && .. && PN()

-> f1()

-> f2()

...

-> fN()

-> <backend>;

r2: ...

...Figure 3: Routes file in eskip

In the above:

- r1, r2, ... are unique routeIDs.

- P1, P2,..,PN are predicates that define the matching.

- f1, f2,..,fN are filters that are applied after the route was selected. Filters can change the request and response.

- Finally, the Skipper backend is defined. This can be a single URL, a list of load-balanced URLs, and others for special cases such as direct response.

The routes string is another dataclient that is handy for tests. For example, if you need a pseudo backend for your demo that replies a green background with HTML, you could use:

$ skipper -routes-string='*

-> inlineContent(

"<html><body style=\"background-color: green;\"></body></html>"

)'Skipper's most popular dataclient, by far, is the Kubernetes dataclient, which is used to fetch information from a Kubernetes API server and create a routing table from Skipper Ingress resources and the RouteGroup custom resource definition (CRD).

To summarize the above, dataclients fetch information from different providers to build Skipper's routing table. Table 1 shows a routing table for the shop/description example, and Skipper uses predicates to select the route to process the request.

Predicates

In Skipper, an incoming request is matched to predicates of all the routes to find the best matching route for an incoming request. Predicates are functions that match based on the incoming request. In the example from Figure 2 and Table 1, Skipper would have a routing table similar to Figure 4:

shop: Path("/")

-> "https://shop.zalando";

product: Path("/detail")

-> "https://product.zalando";Figure 4: Skipper routing table

This means HTTP requests with a path / would be matched by the Path("/") predicate, such that Skipper will execute the shop route. Requests with a path /detail would be matched by Path("/detail") and routed to the product application.

In general, routing behavior can be changed by predicates. There are a lot of predicates you can choose from. For example, Method("POST") will be true only if a POST request would be passed. A route with more predicates is considered more specific. Also, a route with more predicates has more weight in the route selection than one that has less.

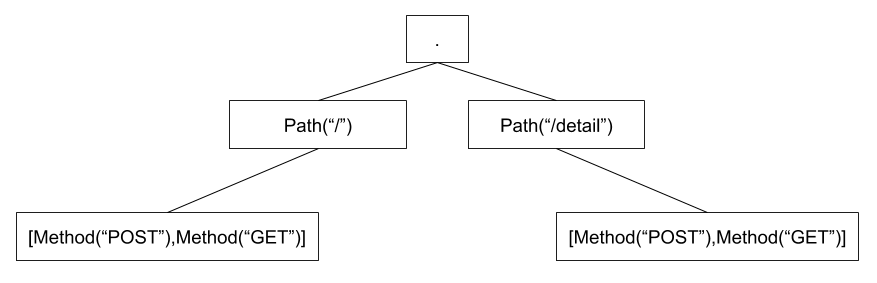

Special cases are Path() and PathSubtree(), which is matched first in a tree and reduces the number of routes, which are scanned as a list. For example, the tree structure shown in Figure 5 helps to scale the number of routes to more than 600,000 in one of Zalando's production setups.

Figure 5: Tree structure

Filters

After a route is selected, the request filters are applied. Filters work on request or response; they can change the incoming request to the backend, and they can change the response to the client.

For example, setRequestHeader("Foo", "bar") sets the HTTP header "Foo" to the value "bar", such that the backend sees this header in the request.

The response filter responseCookie("keks", "val", 3600) sets a Cookie named "keks" in the response to the caller, which might be a browser in this case. The cookie would have the value "val" and is valid for one hour.

One filter that works on request and response is enableAccessLog(40, 5). This would do access logs for all responses from the backend with status codes 40x or 5xx.

As you can see from the examples, filters can change the request or the response or just do some work based on it. Another filter example is auth filters or ratelimits. These would stop requests from passing to the backend if the request should not be allowed to pass. For example, to serve static content from a directory called /var/www, you can use the filter static("/var/www").

Learn more

This article provided a basic overview of Skipper and its capabilities. For more information, consult Skipper's documentation, and please share your questions or feedback in the comments.

6 Comments